Supreme Court Gives Feds a Long Leash To Detain Immigrants With Criminal Records

Conservative majority declines to consider constitutional concerns of holding noncitizens without hearings.

Federal immigration officials have the authority to track down immigrants and noncitizens who have committed certain crimes, months and even possibly years after they've been released, and hold them without bond hearings for potential deportation, the Supreme Court ruled today.

The ruling in Nielsen v Preap was narrowly decided, 5-4, along ideological lines, with the more conservative justices agreeing with President Donald Trump's administration that immigration officials do not need to provide bond hearings and offer the possibility of release to people who have committed certain crimes and are facing possible deportation. And immigration officials have this authority even if they don't get around to detaining these people for months or even years after the offense was committed.

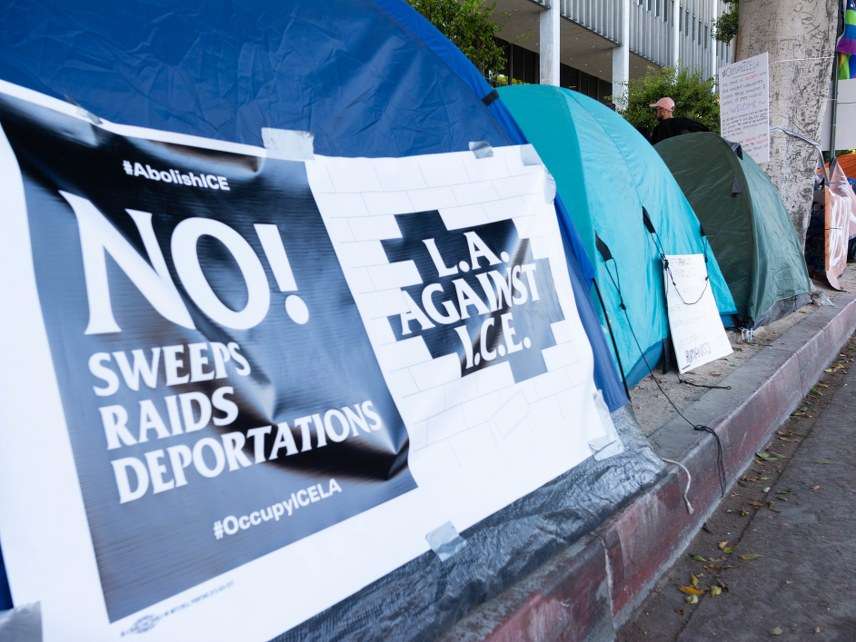

This is a complex and highly technical case, and while there's some coverage suggesting that this is a big victory over sanctuary cities, I'd be reluctant to classify it that way. The ruling does, however, mean that those sweeps where feds come swooping into communities looking for deportable immigrants are potentially even more of a worry for the targets. And sanctuary cities (where local authorities deliberately decline to check the immigration status of people they interact with or share that information with the federal government) are top targets for these sweeps.

So who is this case about? People who are 1.) living in the country completely legally and are not fugitives from justice, who've 2.) been previously arrested, convicted, and even served time for crimes that are deportable under federal law, but 3.) were not deported immediately (or even years) after serving their sentence.

One of the defendants at the heart of this case—Eduardo Vega Padilla, a legal permanent resident since he moved to the U.S. as a toddler in 1966—was convicted of possession of a controlled substance in 1997 and 1999. He was arrested while on probation for that offense when officers found an unloaded pistol in a shed behind his house, and he served six months in jail in 2002. Eleven years later, officials for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) came for him and held him in detention for possible deportation.

Can they do that? And is Padilla entitled to a hearing and possible release from detention so that he can fight his case? Today, the Supreme Court ruled that immigration officials do not have to detain someone immediately after they're released from jail in order to eventually deport them for the offense that landed them in jail; it also ruled that noncitizens who have committed certain crimes (detailed in legislation passed by Congress in the 1990s) are not entitled to a bond hearing that would allow them to fight their case from outside of a jail.

The ruling does not appear to address due process issues or concerns about indefinite detention that might be raised by the Fifth or Eighth Amendments of the Constitution. In the majority decision, written by Justice Samuel Alito and joined by Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts (Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch teamed up to concur in a separate piece), the justices noted that this case was decided over the statutory interpretations of the law and not the constitutionality of it, because the respondents did not challenge whether it was constitutional to detain people like Padilla. They concluded:

We emphasize that respondents' arguments here have all been statutory. Even their constitutional concerns are offered as just another pillar in an argument for their preferred reading of the language of §1226(c)—an idle pillar here because the statute is clear. While respondents might have raised a head-on constitutional challenge to §1226(c), they did not. Our decision today on the meaning of that statutory provision does not foreclose as-applied challenges—that is, constitutional challenges to applications of the statute as we have now read it.

That's something of a hint: if similar plaintiffs want such a case heard again, they need to make a constitutional argument.

In the dissenting opinion, Justice Stephen Breyer (joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan) warned about the significant consequences of such an extreme application of these statutes and argued that these statutes cannot be considered without exploring the constitutional implications:

These aliens may then be detained for months, sometimes years, without the possibility of release; they may have been convicted of only minor crimes—for example, minor drug offenses, or crimes of "moral turpitude" such as illegally downloading music or possessing stolen bus transfers; and they sometimes may be innocent spouses or children of a suspect person. Moreover, for a high percentage of them, it will turn out after months of custody that they will not be removed from the country because they are eligible by statute to receive a form of relief from removal such as cancellation of removal.

We should definitely be concerned of the constitutional implications when it appears Congress has granted the executive branch the authority (and even a mandate) to deny people bail without judicial review. Breyer concluded in his dissent, "I fear that the Court's contrary interpretation will work serious harm to the principles for which American law has long stood."

Read the court ruling here.

Show Comments (117)