Bill Weld: The Next Gene McCarthy or the Next Pete McCloskey?

Richard Nixon faced a primary challenger in 1972...and he squashed him like a bug.

Since announcing a possible GOP presidential primary run last Friday, Bill Weld has been making the national media rounds: ABC's This Week ("I think the Republicans in Washington want to have no election, basically"), CNN's New Day ("I'm trying to get us back in the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln rather than the Know-Nothing, anti-Catholic zealots of the 1850s"), MSNBC's Morning Joe ("Look back to to 2016: The unthinkable became the inevitable twice"), Bloomberg TV, and so on.

In most public appearances, the former Massachusetts governor and 2016 Libertarian vice-presidential nominee has referenced his "favorite stat," which is that "the last nine times a first-term president has sought reelection, the four who had a primary challenge lost, while the five who didn't have a primary fight won another four-year term."

Given Weld's bedrock antipathy to President Donald Trump—"I'm not going to be backing him in 2020, no matter what," he told WMUR—it would seem the best model for his improbable run would be the 1968 anti-war candidacy of Sen. Eugene McCarthy, whose shocking 42 percent second-place finish against President Lyndon Johnson in New Hampshire prompted Bobby Kennedy to get in the race four days later, and LBJ to drop out of the race two weeks after that. Weld has expressed a come-on-in, the-water's-warm attitude toward possible primary competitors John Kasich and Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan, and has stressed, as he put it to ABC, that "it is part of my thinking to make sure [Trump] doesn't repeat, because "we don't have six more years of the antics, frankly."

But there is another historical comp that haunts Weld's possible bid. As Brian Jencunas put it in Commonwealth magazine, "The question isn't whether he wins in New Hampshire, but whether he loses like Eugene McCarthy or Pete McCloskey."

Pete who? Yes, that's kind of the point.

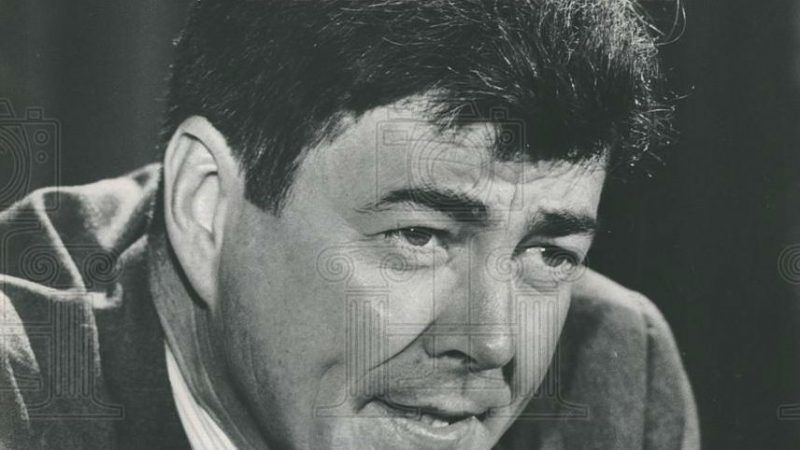

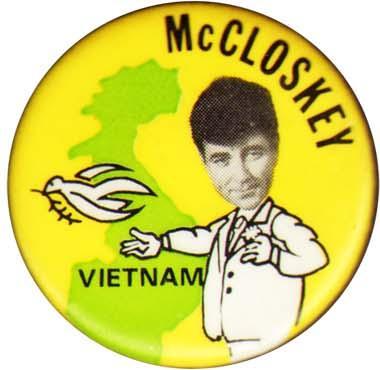

"McCloskey's 1972 anti-war primary challenge against President Nixon went nowhere, winning [20] percent of the vote in New Hampshire," Jencunas wrote. McCloskey, a square-jawed liberal California congressman and Marine vet, dropped out days later, saying he did know who he'd vote for in November.

Nixon, unlike LBJ, did not drop out, nor did he suffer the general-election fate of primary-challenged presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and George H.W. Bush. Instead, after dispatching both McCloskey and conservative Ohio Rep. John Ashbrook (who received 10 percent in New Hampshire), and despite campaigning under a growing legal cloud, Tricky Dick romped to a 49-state, 23-percentage-point shellacking of a Democratic candidate considered to be much further left than the American mainstream.

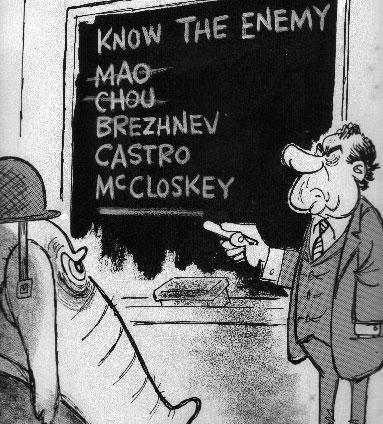

It's not hard to imagine a less one-sided version of that history repeating, particularly given that, as MSNBC's Steve Kornacki reminds us, Trump's approval rating right now among GOP voters beats Nixon's at the time of McCloskey's entrance into the race, 89 percent to 82 percent. This cruel math helps explain why some in #MAGA-land are actively rooting for a primary challenge: A little competition might sharpen the campaign reflexes of a politician who relishes a good political brawl. "At this point," the Washington Post's Ed Rogers wrote this week, "it looks as if Weld et al. are more likely to serve as useful foils for the president rather than serious threats."

Like any historical political analogy, the McCloskey-Weld comparison breaks down in some key areas. On one hand, Bill (unlike Pete) hasn't won an election in a quarter century; on the other, New Hampshire is his literal back yard. He isn't single-issuing the incumbent on war—in fact, pulling troops home from Afghanistan, Syria, and elsewhere is one of Weld's main areas of agreement with Trump. But he does share with McCloskey (who was one of the first Republican congressmen to call for Nixon's impeachment) a sense of revulsion at the president's careless approach to the truth and disregard for separation of powers.

But if Weld does follow McCloskey in becoming a bug on the president's windshield, it's worth remembering that primary challenges can be intra-party referenda on the issues raised by the challenger. After McCloskey's drubbing, the antiwar tradition on the American right went into hiding for the remainder of the Cold War; meanwhile, conservatives tacked not toward executive restraint but toward a robust new definition of expanded presidential power. You can't lay these trends at the feet of a vanquished and largely forgotten primary challenger, but you can observe that a political party becomes more like its president—and less like his critics—over time.

#NeverTrump's "motley collection of neoconservatives, libertarians, moderate Republicans and social conservatives who couldn't stomach Mr. Trump's personal behavior" (in the words this week of glum-sounding Weld fan Liz Mair) might find at the end of primary season that their small ranks within the contemporary GOP have vanished, or at least gone underground.

Bonus Roger Stone angle, courtesy of Jesse Walker:

In 1972, when Pete McCloskey challenged Nixon in the Republican primaries, a young conservative named Roger Stone made a donation to the insurgent's campaign in the name of the Young Socialist Alliance. (The original plan was to use the Gay Liberation Front, but Stone felt that would be an affront to his masculinity.) According to the Senate Watergate Report, Stone and his confederate Herbert Porter then "drafted an anonymous letter to the Manchester Union Leader and enclosed a photocopy of the receipt."

Show Comments (33)