When the World Convulsed, George H.W. Bush (Mostly) Let Freedom Happen

We should, but probably won't, learn the lesson that U.S. presidents don't have to control or even fully understand world events.

The first time I saw a sitting American president give a speech was on November 17, 1990, in Prague's historic Wenceslas Square, on the one-year anniversary of Czechoslovakia's storybook Velvet Revolution. The speaker was George Bush (we did not know his middle initials back then), and I was appalled.

Oh, he was decent and affable enough—always was, just like the Dana Carvey impersonation that did so much to define Bush's public persona. But, my arrogant and impertinent 22-year-old self pointed out with factual accuracy if not quite moral wisdom, the supposed Leader of the Free World exhibited a stunning ignorance of and/or disregard for local and regional facts on the ground.

The warm-up music on that frigid day was a bunch of hymns and marching songs from the American Civil War—this in a country that was already careening toward a nerve-wracking fracture that would happen 26 months later. The speech and pomp were filled with references to God, amongst a people who routinely lead the world in atheism.

More substantively, the U.S. president just didn't seem to have a realistic handle on regional events, which were changing at a velocity almost impossible to convey in 2018. Besides urging in vain for Czechoslovakia to stay together—not an unreasonable ask, given that majorities in both the Czech and Slovak republics favored unification all the way up to the split (it's a long story)—Bush also seemed to think Yugoslavia was a union worthy and possible of saving. I had spent much of the previous month in the tail end of that country, and hostile dissolution seemed inevitable. The first shots would be fired seven months later.

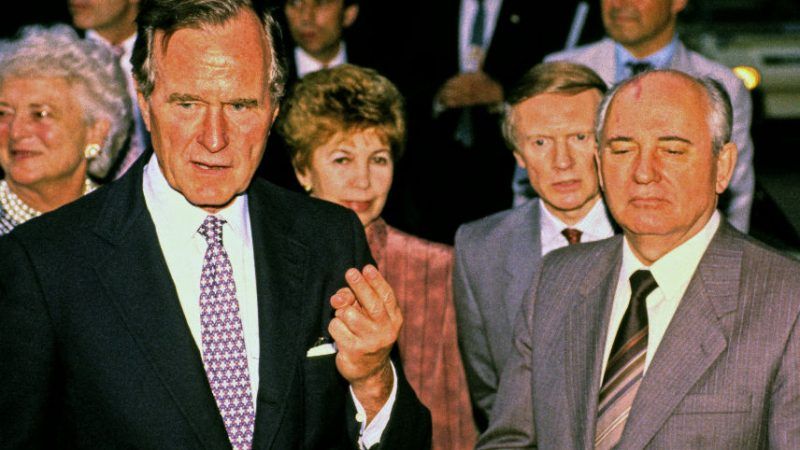

The passage of time has changed my uncharitable interpretation of Bush's flailings. The inability of Washington to properly understand, let alone control, the mostly beneficial convulsions of the 1989-1991 world is a testament to the awesome-if-usually-dormant power of people to cast off their own shackles, at their own chosen speed. The reunification of Germany, to cite one critical geopolitical development, happened with an acceleration that alarmed leaders of East and West alike, from Mikhail Gorbachev to Margaret Thatcher. But Germans willed it to be so.

The further removed we are from historical events, whether through time or geography, the more they seem inevitable. They are anything but. Two months after Bush's Prague speech, Gorbachev sent tanks into Lithuania, killing 14. (The Nation contributor deserves massive credit for rolling back Soviet imperialism from the Warsaw Pact, but he fought bitterly for a unified and still-communist U.S.S.R. until the whoosh of events, too, carried Gorby off stage in late 1991.) Soviet troops only started exiting unwilling countries in the summer of 1991; Kremlin leadership could have gone any which way, and it doesn't take much imagination to create an alternative timeline in which the awful-enough ex-Yugoslav wars became a great-power conflagration.

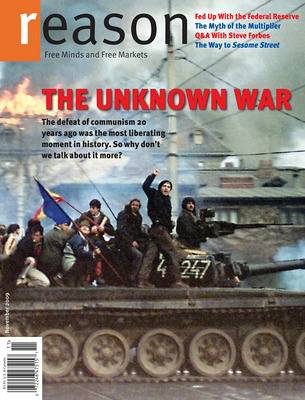

Instead, the world saw the end of superpower proxy wars throughout Africa and Latin America, the collapse of the state-ownership model not just in the East but in Western Europe as well, and the most rapid transformation from unfree to free, socialist to capitalist, in human history.

Bush, like other world leaders of the time, deserves credit not for making all that happen, but mostly for allowing it to happen, in the form of not overly getting in the way. The powerful don't have a particularly good track record when faced suddenly with their own leaking relevance, and with the major and important exception of the Gulf War (which we will be writing more about in this space), Bush handled America's comparative unclenching with admirable calmness.

Former president Barack Obama had it about right earlier this week, at a Rice University event with former secretary of state James Baker: "When it comes to foreign policy, the work that President George H.W. Bush did with Jim at his side was as important and as deft and as effective a set of foreign policy initiatives as we saw in recent years, and deserve enormous credit for navigating the end of the Cold War in a way that could have gone sideways, all kinds of ways."

Things of course did go sideways—they always do at least a little, and some of the blame even for the 2018 geopolitical realities he probably loathed lies at the foot of 41. Bush's dream of creating an international taboo against aggressive violations against other countries' sovereignty, for example, led directly to that laudable principle being serially violated by his own country. By his own son. And by the two presidents since.

That is part of George H.W. Bush's legacy that should, but probably won't, be assessed unflinchingly during the coming tributes. But so should his otherwise non-hysterical statecraft at a time of great tumult. Let one the lessons of his passing be that sometimes American presidents don't have to know it all, and don't have to control it all, either.

Show Comments (20)