Gawker Was Killed for Publishing Embarrassing Truths. That's Bad News.

Giving juries the power to destroy a journalism enterprise for being offensive is bad for free expression.

The old-fashioned belief that free expression is the best way to buttress political freedom, further the quest for truth, and sharpen civic and personal mental acuity is being increasingly abandoned, from thought-leader popular magazines to prominent daily newspaper beat reporters.

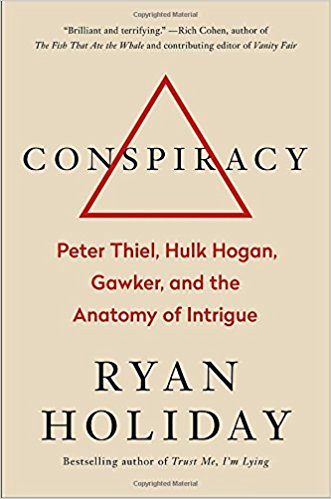

Such speech skeptics believe—and they are not wrong!—that free expression can harm either specific people or the culture at large, and thus deserves to be squashed in some circumstances. That idea animates a fascinating though infuriating new book that tells the story of a publication forced to recant, then be utterly financially ruined, for publishing something true: Conspiracy: Peter Thiel, Hulk Hogan, and the Anatomy of Intrigue (Portfolio Penguin) by marketing guru Ryan Holiday.

This is not a First Amendment story, but it is a story about the power of U.S. government to suppress speech via its tort system. The web publication Gawker was destroyed via lawsuit for invasion of privacy and infliction of emotional distress on wrestler Hulk Hogan (real name Terry Bollea). Gawker published something true—a 1:41 portion of a video of Hogan having sex with his best friend's wife (at said friend's invitation) that Hogan did not know was being shot—and he sued over it.

A Florida court in March 2016 granted Hogan $141 million in compensatory and punitive damages against the publication, its publisher, and one of its writers. (While Gawker could not afford to appeal because a quirk of Florida law requires putting up a bond for the full award pending appeal, the parties eventually settled for smaller amounts that still annihilated Gawker.)

A detail not made public until after Hogan's paralyzing bodyslam to Gawker: Hogan's suit was financed by controversial tech billionaire Peter Thiel. He had his reasons, as Holiday explains via long exclusive interviews with the often press-shy Thiel; mostly, he was mad Gawker outed him as gay in 2007. Thiel was, Holiday concluded from his interviews, consumed with "anger at the unfairness of it…the needless impoliteness of it." Thiel was, says Holiday, a man who "venerated privacy" and considered Gawker literal terrorists for regularly publishing facts about famous (and sometimes not famous) people that those people were embarrassed by.

Was Thiel's righteous anger sincere? It seems unlikely, given that Palantir, a company Thiel founded, happily sells its data-mining services to help the government deport people; or to harass short-term apartment renters; or help cities do "predictive policing."

Holiday's central polemical point doesn't rely on Thiel's sincerity; it is merely that Gawker's publishing the video shamed and hurt Hogan. "No civil society would allow something like this to go unpunished," Holiday concludes.

Was Hogan harmed? Most humans with a hint of empathy would agree he was. Does that settle it? No. Many harms we permit to go legally unpunished. Going into competition with someone's business can harm them. Choosing to start, or leave, a romantic partnership can harm both prospective partners and third parties. Doing something with your own property that violates expectations built around them, even as simple as enjoying it aesthetically, can harm. Deciding to go to the same beach as someone else can harm their enjoyment of that beach. As foes of "political correctness" (which Thiel considers himself) recognize, speaking certain truths or sincerely held opinions related to gender roles or politics, can, in the perception of those who hear them, harm. But a post-Enlightenment westerner should not be quick to think the harm of "violating privacy" should equal "sued out of existence."

It's conceptually untenable to claim a fact (even a fact like "what it looked like while you had sex with a friend's wife") belongs to you because it is about you. Once it is knowledge in someone's mind, or a video in someone else's possession, enforcing such a "right" involves controlling what other people do with their mind, or their property.

A famous 1890 Harvard Law Review article "The Right to Privacy," by future Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis and Samuel D. Warren, launched serious consideration of privacy as worthy of legal protection. The authors rejected the libertarian premise that my right to free speech trumps your right to not be spoken of. Their influential article seems designed to be entered as evidence in the Hogan/Gawker trial, with its complaints that "The press is overstepping in every direction the obvious bounds of propriety and of decency. Gossip is no longer the resource of the idle and of the vicious, but has become a trade…To satisfy a prurient taste the details of sexual relations are spread." Brandeis and Warren thought it could be fine to shut up or punish the press to defend "the more general right of the individual to be let alone."

Using force of law, criminal or tort, to punish expression (always a core element of Western liberty) means the law is not respecting the speaker or publisher's "right…to be let alone." Brandeis and Warren do recognize the distinction between punishment for expressing truly private facts and those of "general or public interest." Brandeis and Warren's instincts match an average Americans' more than they do the average free speech absolutist, but that's why restrictions on expression were supposed to be taken off the table of democracy via the Bill of Rights. (To argue in the alternative like a good lawyer, even if you do believe that the emotional harm of exposing a private fact deserves legal punishment, perhaps some sense of proportionality should be involved such that driving a thriving journalism enterprise out of business should not be the result.)

Even Brandeis, in his 1927 Supreme Court Whitney v. California concurrence, recognized that our Founding Fathers "valued liberty both as an end, and as a means…Fear of serious injury cannot alone justify suppression of free speech….To justify suppression of free speech, there must be reasonable ground to fear that serious evil will result if free speech is practiced. There must be reasonable ground to believe that the danger apprehended is imminent. There must be reasonable ground to believe that the evil to be prevented is a serious one."

Brandeis was able to square his belief in punishing "privacy-violating" speech with that bold paean to the glories and necessities of free speech by believing in a sharp, meaningful line between utterances of public and political relevance and sheer privacy-violating trash. But, as Holiday himself relates, the destruction of Gawker shut up not just pure prurient delight in Hogan's private sexual acts but also lots of journalism of more obvious public importance, including exposing cults, corrupt politicians, and abusive celebrities, stories Holiday admits "the rest of the media would come to seem embarrassingly late on reporting."

The Supreme Court granted in the 2001 decision Bartnicki v. Vopper that a radio commentator should not be legally punished for broadcasting the contents of an illegally intercepted phone conversation (which involved labor unions and a teachers strike and was seen as unambiguously in the public interest). In his opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens admitted that "As a general matter, state action to punish the publication of truthful information seldom can satisfy constitutional standards" and noted "this Court's repeated refusal to answer categorically whether truthful publication may ever be punished consistent with the First Amendment."

But really, a nation with the First Amendment and the philosophical base from which it arose should not find that question hard to answer. Similarly, the power of the state to enforce tort decisions that destroy news publications might also be rethought. Some free speech fans see the principle in the Gawker verdict as so limited—you can't publish a sex tape without permission, big whoop!—that it's not worth fretting over. But that's just the specifics of this case. The principle at issue is whether six people carefully picked by clever lawyers to destroy journalists should be able to do so.

Holiday sloughs over the fact that numerous courts on the way to Hogan's jury victory in Florida saw his case as undeserving. Federal District Judge James D. Whittemore for instance, decided that Gawker's actions were "in conjunction with the news reporting function."

Gawker founder Nick Denton, Holiday's villain, said in deposition in the case: "I believe in total freedom and informational transparency…I'm an extremist when it comes to that. That's why I love the U.S. I love the presumption that expression is free and I want to make fullest use of that liberty that the internet provides." That very free-speech fanaticism, Holiday relates, was key to helping the Florida jurors wonder "what planet do [the Gawker] people come from?" and decreased any sympathy they might have for them.

Because Denton angered Thiel and Hogan, by expressing facts about them they did not want expressed, an entire journalistic empire was murdered. This should not be how America works; the only way to ensure that the whims of judges or juries don't choose what is or isn't legitimate public business (with the literal fate of publications in the balance) is to recognize that even through the tort system, speaking the truth should not leave you open to legal destruction. That a mass market book can uncomplicatedly think the opposite is a sad sign about the cultural state of free expression.

Show Comments (116)