New Mexico Study Suggests Medical Cannabis Helps Chronic Pain Patients Reduce Opioid Use

Yet another cohort study finds a correlation between medical marijuana and reduced reliance on opioids.

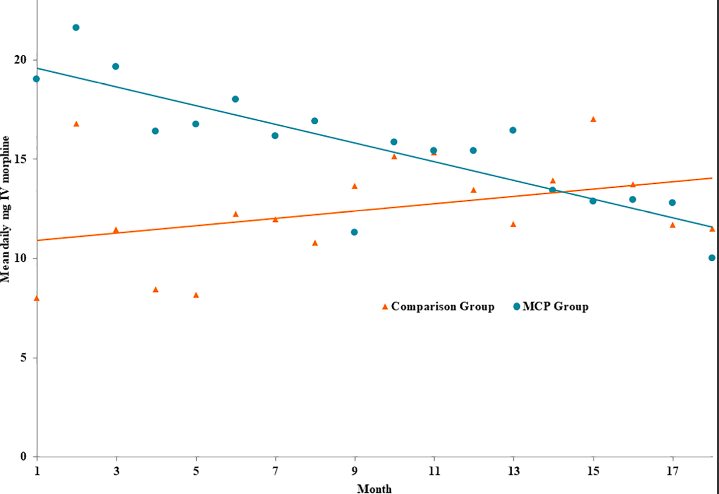

Chronic pain patients who enroll in New Mexico's Medical Cannabis Program while using prescription opioids are likely to reduce their dosage of opioids and even to cease using opioids altogether, according to a new study from researchers at the University of New Mexico.

Participants in the program also reported "improvements in pain reduction, quality of life, social life, activity levels, and concentration, and few side effects from using cannabis one year after enrollment in the MCP."

Published earlier this month in the open access journal PLOS One, the study had a small sample size: 37 of the surveyed patients enrolled in the marijuana program, while 29 used opioids alone. The study also relied on a cohort model rather than a randomized control trial. That means investigators had no say over who ended up in the comparison group versus the Medical Cannabis Program (MCP) group.

The UNM researchers concluded the "clinically and statistically significant evidence of an association between MCP enrollment and opioid prescription cessation and reductions and improved quality of life warrants further investigations." That finding dovetails neatly with a growing body of research that medical marijuana works as well as some prescription drugs for the treatment of pain, while imposing fewer side effects on users.

Researchers at the University of Michigan, for instance, reported in 2016 that chronic pain patients participating in Michigan's medical marijuana program reported a large reduction in opioid use and improved quality of life. Other studies have found that doctors in medical marijuana states prescribe fewer prescription drugs, and that states with legal medical marijuana have experienced a smaller increase in opioid overdose rates compared to states where medical marijuana is not legal.

Albert Einstein College of Medicine announced earlier this year it had received a $3.5 million grant from the National Institute of Health to conduct a five-year study on medical marijuana's potential to reduce opioid use in patients with chronic pain.

The more of these studies I see, the more I'm reminded of something psychiatrist Scott Alexander noted about the renaissance in psychedelic research: "There's a morality tale to be told here about how the War on Drugs choked off vital research on some of the most powerful psychiatric compounds and cost us fifty years in exploring these effects and treating patients." Marijuana's schedule I status precluded it from competing with prescription opioids in the early 1990s as a treatment for chronic pain. That it remains in schedule I, despite a procession of state-level reforms, precludes today's medical professionals and patients from using it the way they use far more potent drugs.

I'm not convinced we need marijuana to be a perfect substitute for prescription opioids, but it seems pretty obvious that chronic pain patients—like PTSD and anxiety patients who want to try MDMA, or depression patients who wish to try psilocybin—would benefit from a wider range of legal drug options than they currently have.

Show Comments (38)