Students Heckled Charles Murray at Michigan, But It Wasn't a Total Disaster

What I saw at the latest campus free speech controversy.

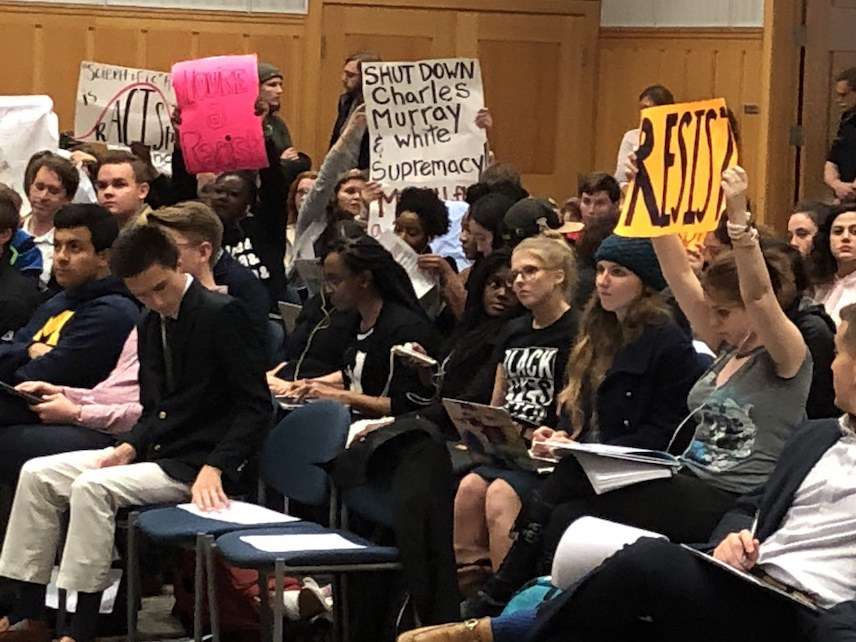

It wasn't a full-blown Middlebury, but Charles Murray's appearance at the University of Michigan last night did feature a familiar mix of protesting, heckling, and walk-outs. Still, the students demonstrating against Murray did not shut the event down, though many told me beforehand that this was their goal.

I have a theory about that.

Two hours before the event, protesters gathered at the Diag, the central area of campus. Some faculty members had teamed with a local anti-fascist group to lead one of the protests; this group did not plan to shut down the event, and was simply focused on responding to Murray's ideas, which they consider to be junk science. (Murray co-wrote The Bell Curve, a book that makes controversial claims about race and intelligence.)

Another group, led by graduate students, planned a coordinated walk-out, but only as a last resort if they failed to get the event shut down. A third group, consisting of students and other local activists affiliated with By Any Means Necessary, also desired an explicit shutdown.

Airport-style security was in effect at the building where Murray was speaking: No sharp objects, umbrellas, or water bottles were allowed. Police officers had to check every bag, which meant that students had to wait in line for an hour before entering the auditorium. The room had space for only 200 students.

Ben Decatur, the American Enterprise Institute's student coordinator at Michigan, kicked off the event by asking the audience to respect free speech principles. But the audience was about 90 percent activists, and they laughed at this idea.

Then Murray took the podium. The heckling began almost immediately. Students shouted at him that he was a white supremacist and a supporter of the KKK. They told him to "get the fuck out of here." They shut off the lights, revealing that activists had somehow arranged for the words "white supremacist" to be projected on the wall behind Murray. Their phone alarms all went off simultaneously. They blasted the Star Wars imperial march, and then, apropos of I'm-not-sure-what, Rihanna's "Bitch Better Have My Money." At least 10 police officers stood idly by as this happened.

The chanting reached a crescendo, and it seemed likely the event would have to be cancelled. But Rick Fitzgerald, a member of the university's public affairs department, took the stage and implored the protesters to let Murray speak. No shutdown took place, and the activists opted to walk out at the appointed time.

The problem with the walkout is that the auditorium only had so much room. By taking a seat with the intention of vacating it in protest of Murray, the activists denied students who actually wanted to watch the event the opportunity to do so. And their heckling made it difficult to hear Murray for much if not most of the event.

But the event was not a Berkeley- or Middlebury-magnitude disaster. There was almost no violence or property destruction—with the notable exception of an observer whose phone was snatched and thrown over a balcony—and the shutdown was averted. I would credit this partial success to Fitzgerald's intervention, and it suggests a potential way to deal with student protests moving forward.

There are no good options for preventing students from shutting down speakers. The nuclear option, of course, is to expel them for doing so. That's something many on the right favor, but administrators and campus security would not necessarily do a good job distinguishing mere protest (which is rightly protected by the First Amendment) from heckling. Universities routinely deny due process rights to students; I have little reason to believe they would do better if they received a mandate to punish protesters. This is why the University of Wisconsin's new anti-protest policy, which is based on a flawed Assembly bill, should worry free speech advocates.

The other option is to do what the College of William and Mary did: absolutely nothing.

But the Michigan event suggests a third way. It is incumbent on administrators, academics in good standing with the left, and other students to stand up to the activists and ask them to turn the dial down. Teach them to be better, and maybe, eventually, they will be.

Show Comments (181)