Professor Injured By Crazed Mob at Middlebury Speaks Out: 'This Was the Saddest Day of My Life'

"They had effectively dehumanized me."

Allison Stanger, a professor of politics and economics at Middlebury College, says the mob of angry protesters who attacked her last week during Charles Murray's visit to campus "had effectively dehumanized me."

"They couldn't look me in the eye, because if they had, they would have seen another human being," she wrote in a post about the incident.

As I reported previously, Stanger had intended to serve as the moderator of the event: a discussion with American Enterprise Institute scholar Charles Murray, the controversial author of The Bell Curve and Coming Apart. In her post, Stanger describes herself as a Democrat who does not agree with Murray, but nevertheless believes campus is a place for a robust debate about a variety of viewpoints.

Stanger's firsthand account of what transpired can be found here. A few highlights:

I agreed to participate in the event with Charles Murray, because several of my students asked me to do so. They are smart and good people, all of them, and this was their big event of the year. I actually welcomed the opportunity to be involved, because while my students may know I am a Democrat, all of my courses are nonpartisan, and this was a chance to demonstrate publicly my commitment to a free and fair exchange of views in my classroom. As the campus uproar about his visit built, I was genuinely surprised and troubled to learn that some of my faculty colleagues had rendered judgement on Dr. Murray's work and character, while openly admitting that they had not read anything he had written. With the best of intentions, they offered their leadership to enraged students, and we all now know what the results were. …

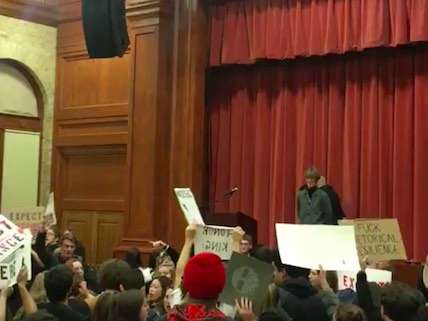

I want you to know what it feels like to look out at a sea of students yelling obscenities at other members of my beloved community. There were students and faculty who wanted to hear the exchange, but were unable to do so, either because of the screaming and chanting and chair-pounding in the room, or because their seats were occupied by those who refused to listen, and they were stranded outside the doors. I saw some of my faculty colleagues who had publicly acknowledged that they had not read anything Dr. Murray had written join the effort to shut down the lecture. All of this was deeply unsettling to me. What alarmed me most, however, was what I saw in student eyes from up on that stage. Those who wanted the event to take place made eye contact with me. Those intent on disrupting it steadfastly refused to do so. It was clear to me that they had effectively dehumanized me. They couldn't look me in the eye, because if they had, they would have seen another human being. There is a lot to be angry about in America today, but nothing good ever comes from demonizing our brothers and sisters.

Stanger goes on to explain how she was attacked outside the event, resulting in a neck injury that landed her in the hospital.

Many have asked, on Twitter and elsewhere, whether the mob that attacked Stanger consisted of students. At this point, we don't know for sure (some of the attackers were apparently wearing ski masks to hide their identities). But the people who protested inside the building were students—some of them, at least. It seems likely to me that at least some of the people who followed Stanger and Murray from one location to another, and then assaulted them, were students.

Murray has written about the altercation as well. He notes that over the last two decades, he has spoken on campuses numerous times. Those appearances provoked protests, but—and this is the key point—never outright censorship. The protesters always maintained an understanding with the administration: they could have their demonstration, but they would be expected to fall silent when it was time for Murray to speak.

"These negotiated agreements have always worked," writes Murray. "At least a couple of dozen times, I have been able to give my lecture to an attentive (or at least quiet) audience despite an organized protest."

This seems like powerful anecdotal evidence in support of my growing suspicion that college campuses are indeed becoming more hostile to free speech. Murray writes:

In the mid-1990s, I could count on students who had wanted to listen to start yelling at the protesters after a certain point, "Sit down and shut up, we want to hear what he has to say." That kind of pushback had an effect. It reminded the protesters that they were a minority. I am assured by people at Middlebury that their protesters are a minority as well. But they are a minority that has intimidated the majority. The people in the audience who wanted to hear me speak were completely cowed. That cannot be allowed to stand. A campus where a majority of students are fearful to speak openly because they know a minority will jump on them is no longer an intellectually free campus in any meaningful sense.

To recap: some students and professors wanted to hear an expert present a viewpoint that isn't well-represented on campus. In response, a mob formed for the explicit purpose of prohibiting this exchange of ideas and punishing—with violence—the people involved.

Murray has called upon Middlebury to punish the students involved as a deterrent against future acts of illiberalism. He's quite right to do so. Administrators must not sit idly by as a minority of radicals destroy the intellectual foundations of the college.

Show Comments (190)