Republicans Want to Cut Taxes, But Not the Size of Government

The tax reform effort is flailing because the GOP doesn't want to reckon with the consequences of tax reductions.

House Republicans passed a budget resolution yesterday, taking an early first step towards overhauling the nation's tax code. But the larger effort is already starting to look like it is in trouble.

A group of senior Republicans released a reform framework last week, but left out many key details that will have to be included in any plan. Overall, it doesn't look like there's been much progress since last year, when a group of influential Republicans released an ambitious but notably (and similarly) vague framework for tax reform.

One of the major pay-fors that Republicans had hoped to rely on going into the year, the protectionist border adjustment tax (BAT), has already been dropped. Republicans also appear to be backing off of a plan to repeal the state and local tax deduction, another major tax code carve out that would raise significant revenue if eliminated. In other words, the same sort of infighting that doomed the health care effort may doom tax reform too.

All of these specific disagreements, however, are just expressions of a more fundamental problem: Republicans want to cut tax rates on corporations and individuals, but they don't want to deal with the consequences of doing so. As a result, they run the risk of turning tax reform into an exercise in expanding government.

Cutting tax rates reduces the federal government's revenue. In a very basic sense, this is the entire point of the exercise. Private actors keep more of their money, and the public sector gets less. But simply reducing revenue, on its own, creates an imbalance between what is spent and what is collected. This is the deficit, which is what contributes to the federal debt. There are three main ways that policymakers can respond to the creation of this fiscal gap.

First, they can raise revenue elsewhere in the tax code. This is the theory behind tax reform: Cut tax rates, but eliminate enough deductions and exemptions so that total tax revenue collected remains the same. Most economists agree that this sort of tax code simplification, which ends distortions and also lowers overall rates, is fairer, more efficient, simpler to administer, and has some potential to improve the economy. In this scenario, taxes come down generally, though taxes for some individuals end up rising.

The problem, of course, is agreeing on which exemptions to eliminate. Each of those exemptions has a beneficiary and some sort of lobbying effort built to keep it in place. The bigger the carve out, generally speaking, the bigger to effort to keep it. Lawmakers whose constituents stand to lose tend to oppose these efforts. As Republicans are already discovering, this dynamic makes it hard to build meaningful consensus on which tax deductions to eliminate or scale back.

Alternatively, policymakers can offset the revenue lost by reducing tax rates by cutting spending. This approach has the advantage of making possible a net tax cut for everyone without raising the deficit. But the problems with this method are similar to those with eliminating deductions: Government spending has beneficiaries, many of whom have organized around keeping that spending in place. In any case, congressional Republicans have given no sign that they are contemplating the sort of spending reductions that would be necessary to offset the tax cuts they favor. The argument they are having right now is entirely about which deductions to cut, not which spending to eliminate.

Finally, policymakers can do nothing at all. This is, in some ways, the easiest course of action, at least from a political perspective. But there is a procedural obstacle to doing so: The reconciliation process that Senate Republicans are planning to use to pass tax legislation with a simple majority does not allow for a deficit increase outside of the 10 year budget window. (It is possible that Republicans will circumvent this restriction with a procedural workaround.)

And there is a bigger, related, downside as well: A tax cut now without corresponding offsets—either spending cuts or additional revenue raisers—is not really a tax cut. It defeats the purpose of the exercise, because it does not actually let people keep more of their money.

Instead, as the Mercatus Center's Tyler Cowen wrote earlier this week, it is merely a tax shift, moving revenue collection from today to years from now, and increasing the nation's debt burden in the process. Indeed, a tax cut today with no offset acts as a sort of subsidy, making government seem cheaper than it really is, while disguising and delaying the costs. It is likely to lead to a tax increase down the road, making it an economically risky proposition that will increase economic instability and extract a greater price on generations to come.

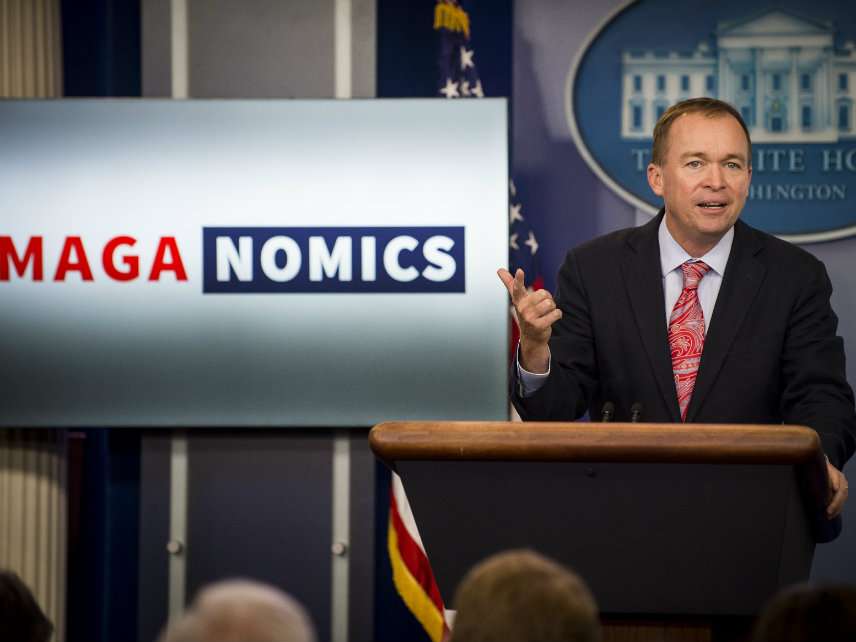

The GOP, however, appears to have chosen to respond by simply denying that it is necessary to fully offset tax reductions at all. White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney, who until recently played the part of a deficit hawk warning about the consequences of a growing national debt, has recently taken to arguing that what the nation needs now are "new deficits" to spur growth.

Many elected Republicans still cling to the belief that tax cuts spur enough economic growth to pay for themselves. Although well-designed tax cuts can boost the economy somewhat, they do not create enough growth to fully or even mostly offset the lost revenue. As a recent study from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget finds, tax cuts do not raise enough revenue via growth to pay for themselves, and never have. Dynamic effects are real, but even in the most favorable circumstances, they do not come close to providing full offsets.

The Republican party, in other words, has chosen to deal with the fiscal consequences of its tax policies by pretending those consequences do not exist. The GOP's mistaken yet persistent belief in the overwhelming power of dynamic effects is politically convenient. But their stubborn fantasy presents a barrier to more stable fiscal policy, to a more streamlined tax code, and to more effective limits on government, because it hides the cost from view. It turns out that what Republicans really want is to cut taxes, but not the size of government.

Show Comments (52)