No Super Bowl Sex-Trafficking Hordes in Houston

Where were all the Super Bowl 2017 sex-traffickers? Living only in activist and law-enforcement imaginations, it seems.

In the weeks leading up to the Super Bowl, the usual cabal of activists, government officials, and click-hungry hacks in the media began their annual process of entirely fabricating an epidemic of Super Bowl-related sexual violence. Once upon a time, the (wholly unsubstantiated) rumor was that domestic violence spiked during big sporting events like the Super Bowl, but for the past decade or so the hysteria has coalesced around sex trafficking. To hear the hysterics tell it, thousands—perhaps tens of thousands—of sex-selling women will flock like cockroaches to cities where sports-fans gather, and only some will be there willingly; the rest, including many children, are trucked in by opportunistic pimps and traffickers.

As ample people have pointed out—see these pieces from author and sex worker Maggie McNeill, theology scholar Benjamin L. Corey, sports writer Jon Wertheim, and journalist Anna Merlan, for starters, or check out this 2011 report from the Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women—there's not a shred of evidence to support this rumor about sports-related spikes in sex trafficking. Any examinations of actual arrest data in Super Bowl cities shows no corresponding spike in sex trafficking, compelling prostitution, or any other similar charge—despite the verifiable spike in law-enforcement and media attention to the issue. Sometimes we see spikes in the number of women arrested for prostitution, but this could be attributed as much to an uptick in vice stings around Super Bowl as an increase in local prostitution levels (and is, regardless, not the same thing as a spike in sex trafficking).

Super Bowl 2017 was held in Houston, which sits in Harris County, Texas. Each day, the county posts its previous 24-hours worth of arrests on the Harris County Sherrif's Office (HCSO) website. The arrest report for February 6, 2017, contains more than 11 pages of arrests, including 12 for prostitution, a lot of DUI and driving-on-a-suspended-license charges, some marijuana possession, several assaults, theft, forgery, driving without a seatbelt, one "parent contributing to truancy," and a few for racing on the highway. The February 7 HSCO arrest log shows three arrests for prostitution. But neither reveals a single arrest for sex trafficking, soliciting a minor, pimping, promoting prostitution, compelling prostitution, or any other charges that might suggest forced or voluntary sex trade.

The Houston Police Department (HPD) does not post arrest logs online, and I unable to obtain any numbers from them directly. I spoke with HPD's public affairs office Monday morning and was told someone would get back to me once the vice department had tallied the numbers, but I have yet to get a response. But the public affairs officer also pointed me to the Harris County District Clerk's Office, which contains case information for people arrested by all in-county police departments, including HPD. Between the Saturday before the Super Bowl and the Tuesday morning after, no criminal complaints were filed against anyone for sex trafficking, soliciting a minor, pimping, promoting prostitution, compelling prostitution, etc.

Falcons and Patriots aren't the only teams at the stadium today- we're proud to work #SB51 with @HoustonPolice @HCSOTEXAS #partners pic.twitter.com/UmtO3hHStD

— FBI Houston (@FBIHouston) February 5, 2017

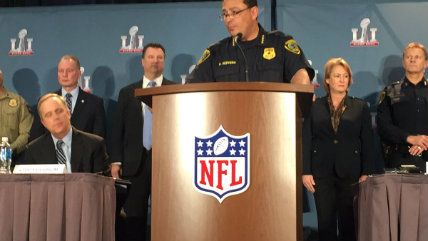

Searching police statements and Houston media likewise turns up no post-Super Bowl mention of sex trafficking, though the subject made plenty of news just before the big game. "As Houston starts to party, there are extra eyes on the crowds," KHOU news reported Thursday after talking to HPD Chief Art Acevado. "Undercover officers are looking for everything from prostitution to human trafficking." At that point, however, they had only made prostitution arrests, booking 22 people on prostitution charges on February 2. KHOU also reported that police "helped get three woman off the streets, one a 19-year-old."

@ArtAcevedo @houstonpolice @HouSuperBowl PLEASE PLEASE watch for innocent females in trafficking!! Save them during SB!!! Help them!

— Robin Hiscott (@hiscott_robin) January 27, 2017

In the days leading up to and following the Super Bowl, Houston Police shared crime info from the department's social media accounts, and Houston news outlets reported on multiple Super Bowl–adjacent shootings, robberies, and other incidents of crime and violence. Neither law enforcement nor the local press mentioned any incidents, investigations, or arrests related to sex trafficking.

In the end, the Super Bowl may have "brought attention to human trafficking," but attention in the absence of a problem isn't anything to celebrate. It's what people today like to refer to as "fake news," and the people who propagate it year after year—police departments looking to justify vice stings and asset forfeiture, missionary groups looking to fundraise or justify federal anti-trafficking grants, sensationalist media, and state and national politicians with human-trafficking measures to promote—are not brave human-rights pioneers and "abolitionists" but propagandists, plain and simple.

Show Comments (34)