The Perpetually Collapsing Political Parties

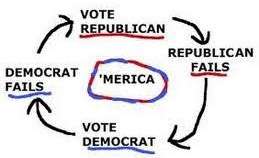

The conventional wisdom see-saws again; now the Democrats are supposed to be doomed.

It has become a tradition in American politics to greet each party's reversals of fortunes by proclaiming that it has been smashed beyond any short-term repair, perhaps even reduced to "permanent minority" status. This week we've seen just how quickly the conventional wisdom can see-saw: After a year of editorials about the decimated state of the GOP, suddenly we've started seeing takes like this:

And this:

And you can see why! The Republicans now control Congress, the White House, and a majority of state governments, and they are about to appoint a justice to the Supreme Court. The Democrats' political operation has turned out to be as hollow as a triple-A rating from Moody's in 2006. As the old cliché goes, the Dems are in disarray.

But so are the Republicans. Donald Trump won the GOP nomination because the party had slipped from its gatekeepers' grasp, and he broke with normal political behavior by continuing to blast away at his Republican rivals even after accepting the nomination. It wouldn't be true to say that he owes nothing to the party establishment—the RNC certainly gave him crucial on-the-ground assistance at the end of the campaign—but he won the election on his own terms and clearly doesn't feel obliged to pay obeisance to anyone. He could conceivably decide to focus on the issues that interest him and let the usual Republican suspects set the agenda for everything else; he could just as conceivably treat Paul Ryan (or Ryan's successor) as the head of another opposition party.

And Trump himself is vulnerable to the same sort of storm that propelled him into office. You younger readers may not know this, but in the long-ago days of 2015 Ted Cruz was seen as a bomb-throwing radical challenging the centers of Republican power. Now the GOP grassroots write him off as a Goldman Sachs puppet who tried to derail the Trump Train. If Cruz and other onetime Tea Party insurgents are already being decried as an old order to be blown aside, Trump may someday find himself in the crosshairs too. Live by the uprising, die by the uprising.

So the Republicans clearly have the upper hand in government, but the Republican Party remains weak, in the sense of not having an orderly, hierarchical structure that can keep everyone in line. The Democratic Party looks pretty weak too—and now that Trump has shown how much of a paper tiger a party's gatekeepers can be, it's entirely possible that a Trump figure will soon arise on the Dems' side of the aisle as well.

These aren't predictions, mind you. Trump could face an insurgency, or he could remake the party in his image. The Democrats could find themselves nominating Bernie Sanders or Kanye West or a sentient Facebook meme, or they could clear the way for yet another grey old pol from the club. The point is how fragile those edifices of party power are, and how much uncertainty that entails. (And how much pure contingency too. If this election had been held a month earlier, maybe Hillary Clinton would be president-elect and the Republicans would be getting bombarded with these your-party-is-a-goner analyses.)

Perhaps this is the kind of unstable situation that just isn't tenable, and the two-party system will eventually break down. You can certainly see signs of dissatisfaction with it: record numbers of people identifying as independents, the strongest third-party results in 20 years, the very fact that a former independent with no institutional loyalty to the GOP can sweep in to take the Republican nomination and then the presidency. If more jurisdictions follow Maine's lead and adopt more pluralistic voting systems, we might finally get a party system that doesn't try to squeeze everybody into just two categories.

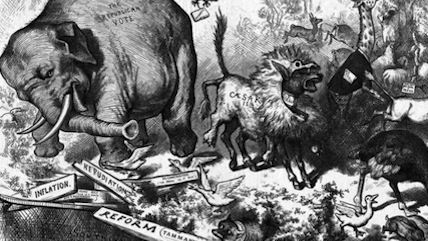

Or maybe not. Maine's new ranked-voting system looks attractive, but Maine is just one state. The rest of us still have a first-past-the-post system that seems to gravitate naturally toward a two-party setup whether or not those parties are institutionally strong. There's a lot of churning in the history of American politics. The parties might just keep remaking themselves, incrementally or not, in a perpetual process of reinvention that only feels like constant collapse.

Show Comments (63)