The Dumbest Attack on Clarence Thomas You'll Read Today

The New Yorker faults the conservative justice for leaving no "footprints" at SCOTUS.

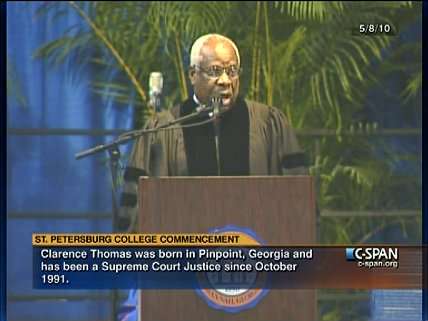

Clarence Thomas was confirmed to the U.S. Supreme Court 25 years ago this month. To mark the occasion, Thomas's jurisprudence has been examined by journalists, praised by admirers, and assailed by critics.

Foremost among the critics is Jeffrey Toobin of The New Yorker. Toobin's dislike of Thomas is well known. Also well known is the fact that Toobin has a bad habit of disregarding the truth when it comes to writing about Thomas. For instance, in February 2014 Toobin labelled Thomas an "embarrassment" because the justice was supposedly half-asleep most of the time on the bench. "His eyelids look heavy," Toobin wrote. "Every schoolteacher knows this look. It's called 'not paying attention.'"

That false description was promptly challenged by court-watchers of various ideological stripes, all of whom agreed that Toobin was full of it. In reality, Thomas is often quite energetic during oral arguments. He doesn't ask questions (well, he mostly doesn't ask questions), but he does actively confer with his neighboring justices, particularly Justice Stephen Breyer, and sometimes, according to Thomas, he even suggests the questions that Breyer and other justices do ask. In other words, Toobin's nonsense was debunked.

Toobin's latest critique of the conservative justice is titled "Clarence Thomas' Twenty-Five Years Without Footprints." According to Toobin, Thomas has left no "footprints" on the Court because he "has never been assigned a landmark opinion." Thomas is a "radical" and a "court of his own," Toobin charges. "After years at the periphery of the Court, Thomas looks destined to serve out his term at the even more distant fringe."

This is a pretty dumb argument, even by Toobin's standards. As any student of the Supreme Court could tell you, some of the most influential justices in American history never wrote a majority opinion in the area of the law in which they ultimately had the most influence. Those particular justices tended to write in dissent—or wrote lone concurrences—yet their arguments slowly but surely moved the Court in their preferred "radical" direction.

For example, consider liberal hero Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. Holmes penned many opinions during his three decades on the Court, but the one that is cited again and again as proof of his wisdom and influence is his solo 1905 dissent in Lochner v. New York, the famous case in which the majority overruled a state economic regulation on the grounds that it did not serve the health or safety of the public and violated the constitutional right to liberty of contract secured by the 14th Amendment. "I think that the word liberty in the Fourteenth Amendment is perverted," Holmes declared, "when it is held to prevent the natural outcome of a dominant opinion." Holmes wanted the regulation to be upheld.

In 1905 Justice Holmes was on the Court's "fringe" when it came to the judicial protection of economic liberty. But Holmes's interpretation found its audience among the assorted politicians, lawyers, intellectuals, and activists who comprised the burgeoning Progressive and New Deal movements. (In the moist words of New Deal adviser and future SCOTUS Justice Felix Frankfurter, Holmes "is led by the divination of the philosopher and the imagination of the poet.") In time, those politicians, lawyers, intellectuals, and activists came to occupy the commanding heights of American government, including the Supreme Court bench. Guess what happened then? In March 1937, two years after Holmes' death, a majority of the Supreme Court adopted Holmes's anti-Lochner interpretation. "The Constitution does not speak of freedom of contract," the Court ruled in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish.

In short, it's cheap and foolish to dismiss a justice for leaving no "footprints" at the Supreme Court simply because that justice is best known for going it alone. At SCOTUS, today's lone voice can become tomorrow's majority opinion.

Show Comments (146)