School System Wants $77K from Michigan Mom to Fulfill Her FOIA Request | Updated!

Sherry Smith just wants to know how the school system decided on placement for her special-needs son.

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) is supposed to make getting documents from the government straightforward. But a Goodrich, Michigan, mom named Sherry Smith is finding out just how crooked the process can be. When she filed a FOIA request for educational records related to her son, Mitchell, the school system told her there would be a hefty price tag—to wit, $77,718.75.

Mitchell has an intellectual disability, which means the state will pay for his education until he turns 26. Having just finished high school, he and his family found a program at a local college they felt was just right for him.

"They would continue special services, life skills, employment skills, all the services that he needed and that he was receiving throughout his entire K–12 school career," says Sherry, "and it includes the academic component, which Mitchell strongly desires." Even more important was that Mitchell would be mainstreamed—"participating fully in his general-ed classes along with his peers," as Sherry put it.

But Goodrich Area Schools denied the Smiths' request, instead recommending placement in a segregated program. Since Mitchell had been mainstreamed since kindergarten, the Smiths couldn't understand the school system's decision.

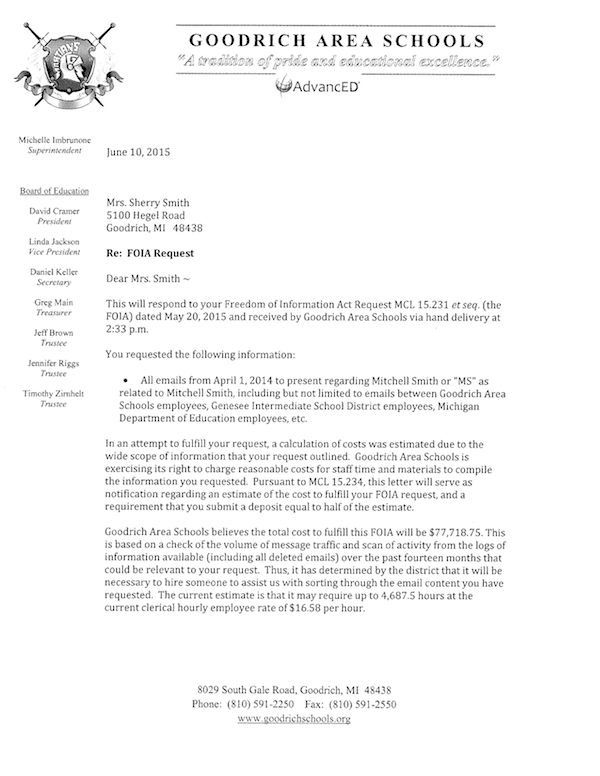

In hopes of gaining some insight, Sherry filed a FOIA request asking for any email communication regarding her son. The school system's response? Per a letter from Superintendent Michelle Imbrunone, which Sherry provided to Reason:

Goodrich Area Schools believes the total cost to fulfill this FOIA will be $77,718.75…It will be necessary to hire someone to assist us with sorting through the email content you have requested. The current estimate is that it may require up to 4,687.5 hours at the current clerical hourly employee rate of $16.58 per hour.

To put that in perspective, that's roughly two-and-a-quarter years of a clerical employee working 40 hours a week on nothing but Sherry's request.

The Smiths ended up retaining Phil Ellison, a Michigan attorney who specializes in FOIA and government transparency–related issues. Ellison says he's "gotten thousands of pages of documents in response to FOIA requests, and the costs were nowhere near what the Goodrich Schools is requesting that Sherry pay."

On July 1, changes to Michigan's FOIA law went into effect. According to the Detroit Free Press:

The law allows requesters who believe they are being overcharged for records to sue and ask a court to lower the fee. If the court concludes the public body arbitrarily and capriciously charged an unreasonable fee, the court must assess $1,000 in punitive damages.

The new law also increases punitive damages from $500 to $2,000 on public bodies that arbitrarily and capriciously break the law by refusing or delaying the release of public records.

With Ellison on board, the Smiths withdrew their original request and filed a new FOIA request July 1 under the amended law.

Additionally, they filed a request under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which gives students and their parents a right to access student records.

Ellison believes this two-pronged approach—using both FOIA and FERPA to try to get the records—is the best tactic to get the school system to hand over the records. "FOIA is the more time-effective…way to get there. FERPA is the more cost-effective, but of course, it takes longer," he says.

Under FERPA, Ellison says, the Smiths should be able to obtain the records for nothing more than the cost of the ink and paper it takes to print them. But unlike FOIA, the Smiths can't sue the school system if it fails to provide the documents under FERPA. "The Department of Education is the enforcement agency on that, and they withhold federal education monies from the school district if they're found to have violated FERPA," says Ellison.

If the school system doesn't respond to the FERPA request within the required 45 days, Ellison plans to file a complaint with the Department of Education, which would prompt a federal investigation and possible sanctions.

While the school system has until early August to respond to the Smiths' FERPA request, Ellison says the deadline for a response to the FOIA request passed July 22 with no response from the school system. His office has filed a legal action against Goodrich Area Schools, arguing the school system improperly denied the Smiths' request by not responding by the deadline.

Ellison says what he sees as an "epidemic level of secrecy" in government is due to the fact that "most of the time when people need records, it's to bring out something where the government has made an error, or miscalculated their discretion, and they don't want to be brought to light their malfeasance, misfeasance, and things of that nature."

Though Ellison thinks the Smiths' is likely a case of government "trying to hide records that probably aren't very favorable to them," he and Sherry both acknowledge it's possible the records will show a valid reason for the school system's denial of the Smiths' request that Mitchell be placed at the local college they selected. If it doesn't, the Smiths will still have to hire a lawyer versed in special-education law to appeal the placement.

"I'm not sure why they placed him where. I suspect that it has to do with politics and money," Sherry says. "That's what I've seen in the special-education system. I've been dealing with it for 14 years, and just about every decision administrators make ends up revolving around money and politics."

The Office of the Superintendent did not respond to a request for comment.

UPDATE 7/29/15: Sherry Smith's attorney has reached out to let us know that earlier today his office received hundreds of pages of emails from the school district. It seems 4,600 hours to complete the FOIA request was a bit of an overstatement. "There was no charge either," he writes.

Show Comments (132)