3 Charts That Show The FCC is Full of Malarkey on Net Neutrality and Title II

As Peter Suderman has noted, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has voted in favor of reclassifying the Internet from an "information service" to being a "telecommunication service" and thus subject to same sort of Title II regulations that have governed voice telephony for decades.

There will now be a long process of what exactly any of this means, followed by inevitable court battles (the FCC is 0 for 2 in recent attempts to expand its authority over the Internet and is hoping this third time will be the charm) and, eventually, possibly some actual implementation of what FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler insists will be "light touch" regulation. Even though Title II rules give the FCC massive power to involve itself in every aspect of how Internet Service Providers (ISPs) go about their business, Wheeler has promised that the agency will in fact hardly use any of the powers granted to the FCC.

Today's vote is a major victory for proponents of Net Neutrality, a somewhat amorphous set of attitudes and policies which generally hold that ISPs should not be allowed to block legal sites, prioritize some traffic over other traffic, or create "fast" and "slow" lanes for the delivery of certain content and services. Clemson University economist, longtime Reason contributor, and former chief economist at the FCC Thomas W. Hazlett defines net neutrality somewhat archly as "a set of rules…regulating the business model of your local ISP."

The typical nightmare scenario that gets trotted out goes something like this: Comcast, the giant ISP that controls NBC Universal, will push its own content on users by simply blocking sites that offer competing content. Or maybe it will degrade the video streams of Netflix and Amazon so no one will want to watch them. Or perhaps Comcast will just charge Netflix a lot of money to make sure its streams flow smoothly over that "last mile" that the ISP controls. Or perhaps Comcast will implement tighter and tighter data caps on the amount of usage a given subscriber can use per month, but exempt its own content from any such limitations.

It's worth noting—indeed, it's worth stressing—that essentially none of these scenarios has come to pass over the past 20 years, despite the lack of Net Neutrality legislation. There have been occasional cases of this or that issue, but they were generally either the result of human error, technological breakdowns, or short-lived policies that customer complaints put an end to. The closest to anything like the nightmare scenarios above involved accusations by Netflix that Comcast and other ISPs were deliberately throttling its streams. Comcast said it was doing no such thing, a perspective supported by researchers at MIT and elsewhere who found that despite huge increases in demand and traffic, Netflix attempted to push its streams via congested parts of the Internet. Netflix eventually agreed to pay Comcast higher fees for what is known as a "peering" arrangement that is not technically a Net Neutrality issue. What the situation actually underscores is that for all the gee-whiz magic of the Internet, it depends ultimately on physical hardware and resources that somebody somewhere has to build, expand, and pay for. Those charges to constantly upgrade and expand capacity will ultimately be borne by content providers such as Netflix, ISPs such as Comcast, and consumers such as you and me.

Commenting on the Netflix-Comcast pissing match at a recent tech conference, Mark Cuban, who made his first big pile with early streaming service Broadcast.com, remarked, "It's a battle between two fairly large companies… [They] worked it out, just like happens in business every day." Cuban, it should be noted, is an archenemy of Net Neutrality and Title II, saying at the same conference that the FCC and the government "will fuck everything up" and "Having them overseeing the Internet scares the shit out of me."

However you feel about Net Neutrality generally and the application of Title II regs to the Internet, it's fair to say that much of the pretext for FCC action is suspect. That is, proponents typically claim that ISPs have monopolies over their local markets, that they offer shoddy and degraded connections, and that the United States is way behind other, more civilized countries whose governments more heavily regulate the Internet.

With that in mind, here are some charts about the current state of the Internet in the United States and elsewhere, some of which come from the FCC's own analysis.

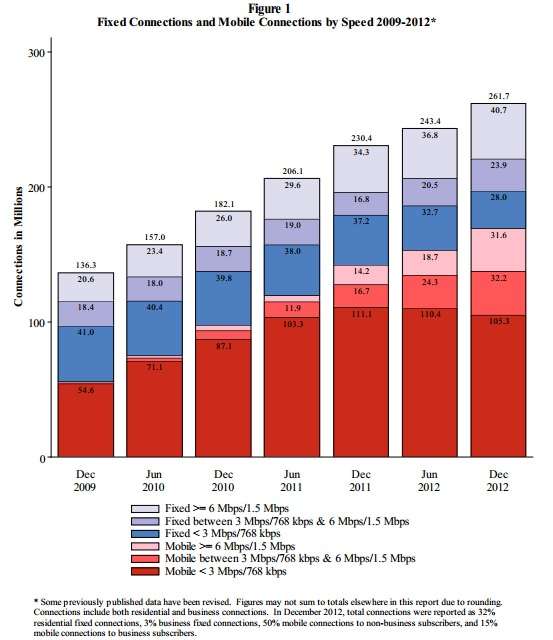

The above comes from the FCC's summary of "Internet Access Services: Status as of December 31, 2012" (the most recent document in the series that I found online). Over the four-year period covered, the number, variety, and speed of Internet connections increased significantly. That's not something you would expect if monopoly conditions actually existed. Given the increasing centrality of the Internet, you might see more people signing up for service, but a true monopoly would have no interest in or need to improve speed or variety of service.

But it turns out, at least according to the FCC—the very agency that now says it needs to regulate the Internet like a public utility in order to ensure a free and open Internet—that the idea of monopoly ISPs is false.

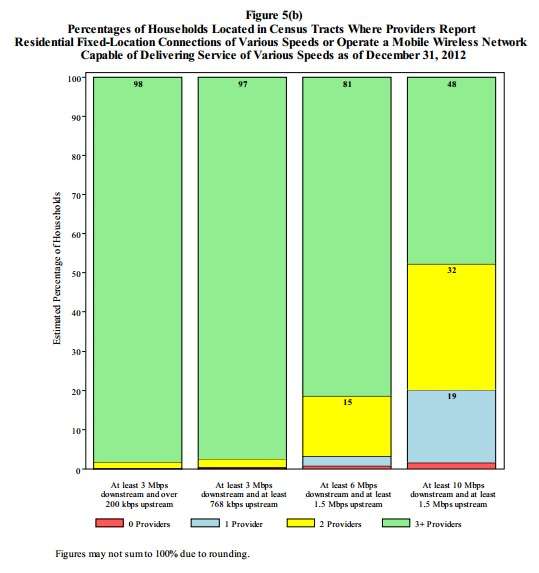

According to this FCC chart, 80 percent of households in America have at least two fixed and/or mobile providers that offer "at least 10 Mbps downstream speeds," which until recently was far above what the agency concerned high-speed broadband. In 2010, the FCC defined as service that offered a 4Mbps downstream and 1Mbps upstream. Just a few weeks ago, it arbitrarily upped its definition to be 25Mbps downstream and 3Mbps upstream. (Net oldtimers will remember the old days of 56k modems and the like.) At the end of 2012, says the FCC, fully 96 percent of households had two or more providers offering 6Mbps downstream and 1.5Mbps upstream service. That may not give you all the bandwidth you want at any given moment, but it also presents a picture different than the monopoly situation that many Net Neutrality proponents rail against. (If you're curious about options in your area, check out the National Broadband Map.)

As important, think about how the delivery of the Internet has evolved, first from a university-based system to early commercial providers using phone lines, then to various types of fixed connections (such as DSL and coaxial cable and increasingly fiber and mobile services). Does anyone think that in 2035 we'll be getting the Internet via a cable that pops up in your living room and also provides televison programs? What increased regulation almost always does is freeze into place existing structures and business models. Certainly that's the case with telephony, where the heavily regulated Bell monopoly fought hard, and for a long time very successfully against all sorts of innovation, from alternative methods of long-distance delivery to accessories such as answering machines to letting people own (rather than rent) their phones. "Communism is a drag, man," Lenny Bruce riffed. "It's like one big telephone company."

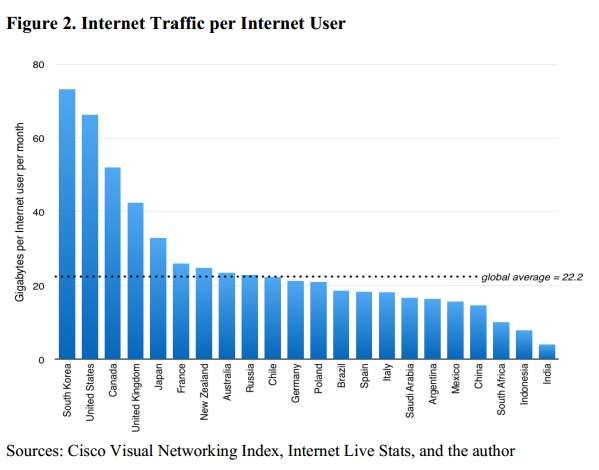

One of the other points that is often raised in Net Neutrality debates is that the United States lags behind foreign countries via virtually any comparison: market penetration, connection speed, cost, you name it. Last November, Bret Swanson, a researcher at The American Enterprise Institute, produced a compelling rebuttal to such arguments, which often relied on misleading data (such as advertised maximum speeds rather than actual delivered speeds) and dubious measures of network capabilities. In "Internet traffic as a basic measure of broadband health," Swanson argues that

Internet traffic volume is an important indicator of broadband health, as it encapsulates and distills the most important broadband factors, such as access, coverage, speed, price, and content availability. US Internet traffic is two to three times higher than that of most advanced nations, and the United States generates more Internet traffic per capita and per Internet user than any major nation except for South Korea.

Here's one of his figures:

The thrust of Swanson's basic argument is also supported by the annual "State of the Internet" reports produced by cloud-computing service Akamai, which typically shows the United States doing well in most comparisons.

Nobody loves his or her ISP. I know I don't—and I speak as someone who has dealt with virtually the entire rogues gallery of major players. However, the question isn't simply whether Comcast has the shittiest customer service in the country (it does), it's whether the company's products are getting better and whether it faces more or less competition based on market forces.

And that, to me, is quite possibly the most frustrating aspect of the Net Neutrality and Title II debate. To the extent that cable companies once had absolute local monopolies, it was precisely due to local governments granting them that. There are all sorts of things that local, state, and federal governments—not to mention nominally independent agencies such as the FCC—might do to reduce or remove barriers to entry for competitors. As FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai told Reason in an interview released yesterday,

There are a lot of markets where consumers want and could use more competition. That's why since I've become the commissioner, I've focused on getting rid of some of the regulatory underbrush that stands in the way of some upstart competitors providing that alternative—streamlining local permit rules, getting more wireless infrastructure out there to give a mobile alternative, making sure we have enough spectrum in the commercial marketplace—but these kind of Title II common carrier regulations ironically will be completely counterproductive. It's going to sweep a lot of these smaller providers away who simply don't have the ability to comply with all these regulations, and moreover it's going to deter investment in broadband networks, so ironically enough, this hypothetical problem that people worry about is going to become worse because of the lack of competition.

Pai calls the new rules "a solution that won't work to a problem that doesn't exist." I think he's right about that and it should give even the most uncritical supporter of the FCC action pause that the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a robust supporter of Net Neutrality, has seen fit to write a "Dear FCC" warning:

The FCC will evaluate "harm" based on consideration of seven factors: impact on competition; impact on innovation; impact on free expression; impact on broadband deployment and investments; whether the actions in question are specific to some applications and not others; whether they comply with industry best standards and practices; and whether they take place without the awareness of the end-user, the Internet subscriber.

There are several problems with this approach. First, it suggests that the FCC believes it has broad authority to pursue any number of practices—hardly the narrow, light-touch approach we need to protect the open Internet. Second, we worry that this rule will be extremely expensive in practice, because anyone wanting to bring a complaint will be hard-pressed to predict whether they will succeed. For example, how will the Commission determine "industry best standards and practices"? As a practical matter, it is likely that only companies that can afford years of litigation to answer these questions will be able to rely on the rule at all. Third, a multi-factor test gives the FCC an awful lot of discretion, potentially giving an unfair advantage to parties with insider influence.