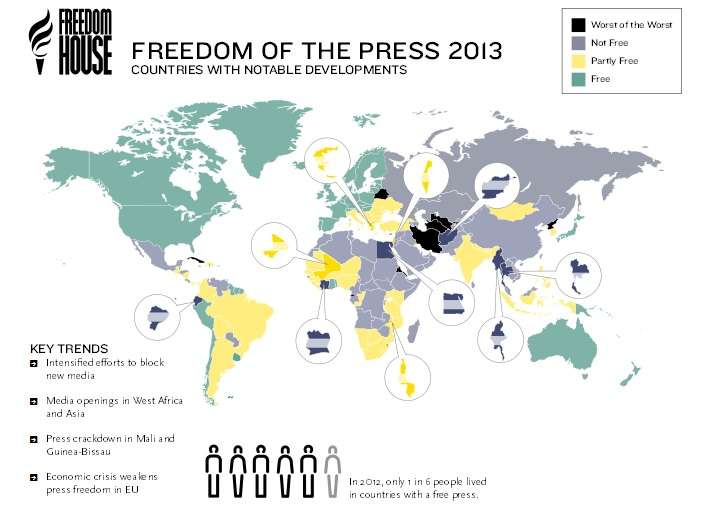

Global Press Freedom Looks Pretty Shaky, Says Freedom House

Over the past year, Britain has debated, and is on the verge of implementing, a scheme for state control of the press, even as media outlets put up fierce resistance. South Africa's parliament passed a bill putting journalists in danger of espionage charges. The European Union pushed for state regulators to ensure the press upholds "European values" and "the public function of the media." The EU also funneled funds to local advocates of the same. Other generally open countries, including Australia and New Zealand, either narrowly averted state domination of the press or else continue to mull the idea. So, it's with trepidation that we peek through our fingers at Freedom House's 2013 report on the state of press freedom around the globe and … oh. That's not good.

As Freedom of the Press 2013 puts it:

Ongoing political turmoil produced uneven conditions for press freedom in the Middle East in 2012, with Tunisia and Libya largely retaining their gains from 2011 even as Egypt slid backward into the Not Free category. The region as a whole experienced a net decline for the year, in keeping with a broader global pattern in which the percentage of people worldwide who enjoy a free media environment fell to its lowest point in more than a decade. Among the more disturbing developments in 2012 were dramatic declines for Mali, significant deterioration in Greece, and a further tightening of controls on press freedom in Latin America, punctuated by the decline of two countries, Ecuador and Paraguay, from Partly Free to Not Free status.

I think the key phrase here is, "the percentage of people worldwide who enjoy a free media environment fell to its lowest point in more than a decade." That's not a good development, even allowing for those lucky places that swam against the current and either gained or retained a little more liberty to cover and criticize the doings of the powers that be.

Note, however, that some countries get dinged not because (or, at least, not just because) of increasingly unfriendly legal environments for press outlets, but also because traditional media companies may be under economic pressures that cause, for example, established newspapers to cease publication. It's unfortunate when a media outlet can't continue to operate, but it doesn't necessarily follow that the market once served by that newspaper is now less free. It doesn't even follow, in the world of blogs, Twitter and Facebook, that the market is now less informed. Greece is rightly taken to account for "heightened legal and physical harassment of journalists," but also for "closures of, or cutbacks at, numerous print and broadcast outlets." Those closures are sad, but not surprising, in a country suffering an economic implosion, and they don't represent the same sort of phenomenon as legal targeting of journalists. Likewise, Israel's "indictment of journalist Uri Blau for possession of state secrets, the first time this law had been used against the press in several decades," seems a much more legitimate complaint than the closure of the newspaper, Maariv, because it couldn't compete with Israel Hayom, a popular free daily.

What's interesting is that we live in an age of exploding outlets for information. The Internet, social media, Twitter and a range of new technological means for sharing text, images, audio and video reports about what is going on as it's going on have empowered individuals and organizations as never before to spread information far and wide. These new capabilities also frighten government officials. Notes Freedom House:

The trend of overall decline occurred, paradoxically, in a context of increasingly diverse news sources and ever-expanding means of political communication. The growth of these new media has triggered a repressive backlash by authoritarian regimes that have carefully controlled television and other mass media and are now alert to the dangers of unfettered political commentary online.

While bloggers and tweeters can be (and have been) arrested just like old media journalists, new media tends to be more elusive and harder to control than newspapers and broadcasters with their brick-and-mortar locations. The result may well be governments that step up their efforts at control even as information slips through their fingers as never before. That's not an ideal situation, with less than 14 percent of the world's inhabitants living in countries where press freedoms are respected, but it's certainly better to live in a world in which technology makes control of the media exceedingly difficult than to live in one where the repression detailed in this report is as effective as it might have been in the past.

Show Comments (118)