Tennessee's Haircut Cops Bust Barbers Who Lack High School Diplomas

Elias Zarate found out the hard way that it's illegal to cut hair in Tennessee, and some other states, without having graduated from high school.

The Tennessee barber cops caught up with Elias Zarate on January 18, 2017.

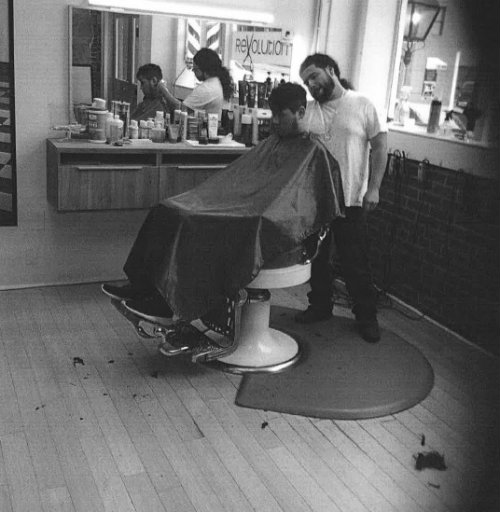

Zarate was working upstairs at The Revolution Studio, a small barbershop on trendy Front Street in downtown Memphis. The job, which he had held for only a few weeks before getting busted, was like a dream come true for Zarate. He'd learned to cut hair while helping out in his uncle's barbershop as a kid, and he had honed his skills over the years by cutting his siblings' and friends' hair. At Revolution, Zarate had served clientele from ordinary working-class to members of the Memphis Grizzlies, the local NBA team.

But getting that job required a state-issued license. Zarate had bought one a few months earlier from a friend "who knew a guy." He wondered at the time if the license was legitimate, but the opportunity seemed too good—and why shouldn't it be that easy to get a barber license?

The license, of course, was a fake. No one can just buy a license to be a barber in the State of Tennessee, or anywhere else for that matter. Obtaining one requires years of schooling, passing various exams, and the paying fees to the state Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners.

Jerry Biddle, the field inspector from the Tennessee Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners who stopped by the Revolution Studio that day, quickly spotted the fake.

"He came straight to me and was like, 'That license is fake,'" remembers Zarate.

Biddle's report of the incident is straightforward. He entered the barbershop. He witnessed Zarate cutting hair. He checked Zarate's license. It was not valid. He questioned Zarate, who admitted that he'd never been to barbering school. It was a run-of-the-mill investigation and an open-and-shut violation of Tennessee Cosmetology Act code 62-4-108: "person without a valid license practicing." There's nothing in the report—nor in other legal documents that eventually became part of Zarate's case—that suggests any concern about the 28-year-old's skills with scissors and a razor, or that indicates Zarate had done anything to put customers at risk. It's a simple matter of not having the right paperwork.

For Zarate, the confrontation was more memorable.

"They put fear in you. You know, they make you feel like they're going to come get you and put you in jail," says Zarate. "I just felt like I was dealing with the police."

And that was just the beginning of his ordeal. After dealing with the barbering police, he had to face the barbering courts.

The citation he received on January 18 required Zarate to appear before an administrative judge at a formal hearing of the state Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners in Nashville. With no previous experience in dealing with state licensing boards or navigating the quasi-judicial workings within them, Zarate assumed the hearing would clear up some of his confusion about what he had to do to get a legitimate license.

The hearing went quite differently. He didn't have an attorney, and because it was an administrative hearing, he wasn't provided one. In all other ways, it was essentially a trial. There was a judge, a set of witnesses (including Biddle), and evidence filed by the state.

"I thought it was to tell me what I'd done wrong or how to go about getting my license or getting right with the state," he says. "Once I got there, though, it was a full-on case against me. They slaughtered me."

He was hit with a $1,500 penalty, followed by $600 in additional fees that included court costs, attorneys' fees, and the expense of the investigation that had busted him for the fake license. There was no information about how to get licensed correctly. The state didn't want to help him. It just wanted money.

"I was thinking, how am I supposed to pay for this fine, you know, because they're stopping me from working," Zarate says. He tried to follow the process for appealing the fine, sending a letter to the board in mid-September pleading his case and requesting help. The appeal was flatly denied.

Still wanting to make things right with the state, and wanting to provide a steady income to support his new wife, who was expecting a daughter, Zarate began calling around to barbering schools in the Memphis area. That's when he hit another wall.

Without a high school diploma or a GED, he was repeatedly told, there would be no reason for a school to admit him.

Nearly a decade earlier, Zarate had dropped out of high school. He'd made it to the 12th grade, but he had a failing GPA and spent most of the school day sleeping through classes because he was exhausted from working a series of after-school and weekend jobs. His mother had died when he was just 10 and his father had left the family soon after, leaving Elias and his two younger siblings in the care of relatives. That situation was untenable, so when an opportunity arose to work and live in Memphis—about 20 miles from where he was living at the time—Zarate had no second thoughts about leaving school.

At the time, he never would have guessed that failing to finish the 12th grade could prevent him from working as a barber. Even now, he's somewhat stunned by the law.

"I don't feel like anything in my entire schooling from grade school through senior year had anything to do with my barbering skills," he tells Reason.

All licensing rules are at least somewhat arbitrary, and all licensing rules limit access to jobs in licensed professions, but the disconnect between mandatory training and the danger posed by unlicensed individuals doing the exact same work is rarely larger than it is in the barbering profession—and Tennessee's barber licensing law is an outlier.

It's also a policy with no justification except protectionism. Cutting hair well does not require knowledge of trigonometry or a careful study of the meaning of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Proper sanitation for the equipment used by licensed barbers—the only thing that could remotely be considered a reason for government to intervene in the process of determining who can be a barber—could be, and indeed is, taught during the mandatory training that all barber licensing applicants must complete in Tennessee. It is not taught in Tennessee high schools, for obvious reasons.

"I don't feel like anything in my entire schooling from grade school through senior year had anything to do with my barbering skills."

Tennessee's requirement that would-be barbers graduate from high school is not some relic from a by-gone era. The law was passed in 2015.

Before then, obtaining a barber's license (technically called a "certificate of registration as a master barber") required an applicant to show that he or she had completed the 10th grade. In other words, when Zarate dropped out of school in the 12th grade in 2008, he would have been eligible for a barber license. By the time he sought the license, in 2017, he was not.

Legislative records show that there was little debate on the bill—it was HB 1332 and SB 964 during that session—as it moved through the legislature. The legislation was presented as an effort to "clean up" differences between the state's cosmetology and barbering licensing rules following the merger of the two boards into the newly formed Tennessee Board of Cosmetology and Barber Examiners. But the bill actually hiked schooling standards for barbers while ignoring similar requirements for cosmetologists. Getting a cosmetology license in Tennessee requires only that an applicant has completed the 10th grade.

In addition to increasing the legal requirements for barbering in Tennessee, the bill hiked the punishments for anyone caught barbering without a license. Under the new rules, the offense is now a Class A misdemeanor punishable under Tennessee law by up to 11 months and 29 days in jail along with fines of up to $2,500. Before, it was a Class C misdemeanor that carried no more than 30 days in jail and a $50 fine.

The changes may have been rooted in protectionism. Until 2013, one of the states that borders Tennessee—Alabama—had no state license for barbers. The head of Alabama's cosmetology board, who was a leading proponent of the 2013 license, explicitly favored it on the grounds that it would protect cosmetologists from "unfair competition" by barbers. Was a similar motive at work in the Volunteer State?

The Tennessee bills' sponsors—state Sen. Mike Bell (R-Riceville) and state Rep. Antonio Parkinson (D-Memphis)—did not return calls for comment.

Only 13 other states require completion of high school as a prerequisite to getting a barber license. Others states have varying requirements mandating the completion of anywhere from 7th to 10th grade, but 16 states have no educational requirements beyond passing a barbering exam.

"This means Elias could enter barber schools in 37 other states," says Dick Carpenter, director of strategic research for the Institute for Justice, a national libertarian law firm that frequently takes challenges on behalf of people who have been harmed by state licensing schemes. (They are not involved in Zarate's case.) "In fact, he could do so in six of the eight states that border Tennessee."

The closer you look, the less sense it makes. You can become a licensed emergency medical responder in Tennessee without a high school diploma—indeed, you can do it with far less work than is required to become a barber. Getting an EMR license in Tennessee requires only that an applicant can "read, write, and speak the English language," according to Tennessee Department of Health guidelines.

"You can restart the heart of a pulseless, unbreathing person without a high school diploma, but you cannot cut hair," says Braden Boucek, director of litigation at the Beacon Center, a Nashville-based think tank.

Today, the Beacon Center sent a letter to the state board asking it to eliminate the high school completion requirement for barbers. "The job market is rough enough for high school dropouts without artificially denying them entry into one of the few dignified and stable fields that a person can do without a high school degree," Boucek argues.

The unemployment rate in Tennessee was 3.1 percent in November 2017, the most recent month for which data is available. That's a full percentage point lower than the national average. But high school drop-outs have a significantly harder time finding work. Men without high school diplomas were unemployed at a rate of 6.6 percent last year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' annual population survey.

Anything someone like Zarate would need to learn about barbering could be taught in the mandatory 1,500 hours of training he would receive before taking his licensing exam.

Students who don't have high school diplomas or equivalent degrees can be accepted into a Tennessee barbering school, but schools are forbidden under state rules from giving financial aid to those who do not have a diploma or GED, says Fred Ross, admissions director for the Memphis-based The Barber School. Ross estimates that 99 percent of students in his school received some form of financial aid, so the diploma requirement functions as a de facto prohibition for anyone, like Zarate, who is unable to pay for barbering school out of pocket.

But getting into a barbering school isn't what really matters here. Graduating from a barbering school makes no difference, under Tennessee state law, if the graduate does not also have a high school diploma.

The $1,500 fine levied against Zarate is typical of what first-time offenders face, says Kevin Walters, communications director for the Tennessee Department of Commerce, which oversees the state's professional licensing boards. As far as the state government is concerned, the matter is closed.

"This matter was heard and adjudicated by an administrative law judge sitting on behalf of the board," Walters tells Reason. "The Initial Order entered by the administrative law judge became a final order and as such this matter is legally adjudicated and cannot be further amended or appealed."

Zarate's saga has some things in common with another outrageous licensing story that Tennessee lawmakers have promised to address in 2018.

Last year the Tennessee Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners threatened two women with fines and jail time because they were offering equine massages without being licensed as veterinarians. Like the high school requirement for barbers, the mandate made little sense. Laurie Wheeler and Martha Stowe were already experts in their professional fields—Wheeler has worked with some of the top competitive equestrians in the state—and spending two years and thousands of dollars on veterinary school would not teach either of them anything she needed to know. It was an arbitrary requirement with little relationship to the public interest. All it did was eliminate possible competition for veterinarians who might offer similar services.

Most licensing rules are less about protecting the public and more about protecting the license holders. Professional licensing boards are essentially "cartels by another name," according to Aaron Edlin and Rebecca Haw, two University of Pennsylvania law professors who published a paper in 2014 arguing that unscrupulous licensing boards should face antitrust lawsuits. Dental boards have tried to stop non-dentists from doing things like whitening teeth. Florist licensing boards have limited who can arrange flowers professionally in order to protect the public from the scourge of contaminated dirt. In California, a state law prohibits teaching someone how to be a farrier—that is, someone who makes and fits horseshoes on horses—unless the student has a high school diploma.

In the Tennessee horse massage case, state lawmakers intervened and passed a temporary fix to the law near the end of the 2017 session; a more permanent fix could be in the offing this year. Boucek hopes that legislative reform will solve Zarate's problem as well, and that a lawsuit will not be necessary. In the meantime, a GoFundMe account has been set up to help Zarate pay the fines.

Looking back on the past year, Zarate says he's learned a lot about a system that he never knew existed. Not that it's helped him get any closer to getting his license. He acknowledges that he made a mistake by falling for the licensing scam, and he says he wants to put everything right. He just doesn't know how long that's going to take. With greater perspective on how the system works, he now wonders how many other people have run into the same barriers.

It doesn't really matter, in the end, whether Zarate was scammed into buying the fake license or whether he was aware of what he was doing. Either way, the state's requirement that barbers must graduate from high school is equally unnecessary.

"It goes back," he says, "to the pursuit of happiness." He pauses. "I feel like they have taken away my freedom."

Show Comments (40)