Delaware's Odd, Beautiful, Contentious, Private Utopia

Arden is a suburb, an artist's colony, and a radical political experiment.

They held a town pageant in Arden, Delaware, on September 5, 1910: a medieval procession with performers dressed as knights, troubadours, pages, and squires. One Ardenite, an anarchist shoemaker named George Brown, played a beggar. This annoyed some of the other players, because no such role had actually been written. But Brown decided to add it to the program anyway, so he dressed in rags, caked himself with mud, and invaded the proceedings, taunting the other characters and demanding alms from the audience. Many "onlookers needed assurance," The Single Tax Review reported, that Brown "was only 'part of the show.'"

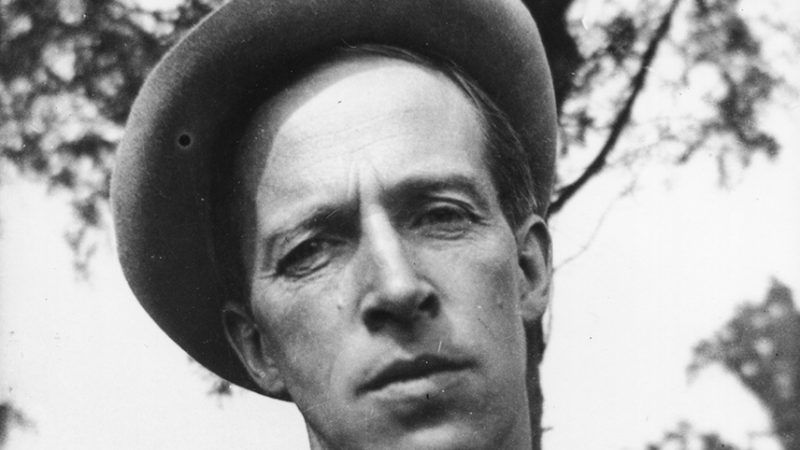

This was a pattern: Brown liked to talk, and not everyone liked to listen to him. According to the novelist Upton Sinclair, who lived at the time in a little Arden house that his neighbors had dubbed the Jungalow, Brown insisted on "discussing sex questions" at the Arden Economic Club. When the club asked him to cut it out, Brown declared his free-speech right to continue and kept talking until he'd broken up the meeting. He broke up the next meeting too, and finally, Sinclair wrote, "declared it his intention to break up all future meetings."

At this point some of the locals wanted to have him arrested for disturbing the peace. But that required outside help, because the town of Arden did not have a police force.

In fact, the town of Arden didn't have a government at all. Not, at least, in the usual sense of the word.

I should back up and explain a few things. Arden's origins go back to the Delaware Invasion of 1895 and '96, when the Single Tax movement tried to take over the state. The Single Taxers were followers of Henry George, a 19th century economist who argued that government should be financed solely by a tax on land values. No income tax, no sales tax, no tax on the improvements to a property—just one tax on land. The campaigners crisscrossed the state in armbands, knapsacks, and Union Army uniforms, delivering streetcorner speeches and singing Single Tax songs ("Get the landlords off your backs/With our little Single Tax/And there's lots of fun ahead for Delaware!"). More than a few got tossed in jail for their efforts.

The invasion was a flop. A disaster, really. Not only did their gubernatorial candidate get only 2.4 percent of the vote, but within a year the movement's foes would insert a provision into the state constitution that made a George-style tax impossible.

Unable to achieve their ideas at the ballot box, a group of Georgists decided to take another approach. In 1900 they acquired some farmland outside Wilmington, created what amounted to a community land trust, leased out plots to anyone who wanted to move in, levied rents based on the value of the unimproved land, and used the rent money to pay for public goods. In other words, they set up a private town and enacted the Single Tax program contractually. And with that double experiment in communalism and privatization, Arden was born.

I just called Arden a "town," but for its first few years it was essentially a summer resort. (Or a summer camp—many of the part-time residents slept in tents.) But by the end of the decade, particularly after the founders made some tweaks to the lease agreement in 1908, a year-round community had formed. It was a largely lower-middle-class crowd, with a high number of artists and craftsmen; it attracted not just Georgists but other sorts of nonconformists, from socialists to vegetarians. And anarchists, like our sexually explicit friend George Brown, who kept a cottage there with his common-law wife.

The Ardenfolk had institutions—the trustees who set the rents had a certain degree of power, and there were regular town meetings too—but they weren't a municipality and they didn't have any police. So in July 1911, aggravated by the shoemaker's antics, a group left the town limits, found the appropriate authorities, and swore out a warrant for Brown's arrest.

Not everyone in the colony liked this idea. "They did not want any 'laws or lawing in Arden,'" The New York Times reported, because "once the pernicious things came in there would be no getting rid of them." But the warrant was issued, and Brown ended up spending five days in the workhouse.

He soon got his revenge. While incarcerated, Brown claimed, he had an epiphany that "the Law is supreme and must be obeyed." And so he swore out a warrant of his own against Sinclair and 10 other Ardenites for violating Delaware's blue laws. The Arden 11 wound up serving 18 hours behind bars for the crime of playing baseball, playing tennis, and selling ice cream on a Sunday.

After the prisoners' sentences were completed, the town celebrated with a circus. The performance included an arrest of its own: A clown dressed as a cop entered the audience, grabbed a surprised Sinclair, and marched him away from the show.

Zen Suburbs

"I've spent more time debating things in the grocery store than I did buying that house," says Denise Nordheimer. "It was an impulse buy."

We're sitting in the Buzz Ware Village Center, where the Arden Community Planning Committee has been mulling such matters as a community garden and a bridge. The year is 2017, and everyone involved in the George Brown caper of 1911 is long dead. Yet Arden is still here, a little shire surrounded by an otherwise ordinary suburban landscape. It's a maze of narrow roads, abundant forests, and houses that look nothing like each other, some of them sporting engagingly unusual pieces of art in their yards. The place did eventually acquire a municipal government, but it took until 1967 for that to happen, and the change didn't represent a major shift in how the town was run so much as a convenient shell when dealing with the state and county authorities.

The place has even spawned two spinoffs, the neighboring villages of Ardentown and Ardencroft. Both are run on the same general principles. The three communities, known collectively as The Ardens, have a combined population of about 1,000 people. Nordheimer, an attorney, has been one of them for about a decade now.

In 2007 she and her family owned a home in Wilmington. Life was perfect, she says—"everything was just the way I wanted it"—except they lived on a busy street and her 7-year-old daughter was too nervous to ride a bike. "We just realized that she needed more physical independence and she was never going to get it at that house," says Nordheimer. "We always needed to supervise her."

"We have to move," she told her husband. "She's not learning to ride her bicycle."

"I'll move," he replied, "but I want more Zen."

Nordheimer quickly found that you couldn't do a real estate search for "Zen," so she did the next best thing, which was to poke around semi-randomly online for houses in their price range. She had never heard of Arden, but she found a photo of a home there that looked like it had "Zen off the charts," so they went to check it out.

"You have to buy that house," her daughter said when they got home.

"Oh, you liked it?" said Nordheimer.

"No," the girl replied, "but I made a friend on the playground right in front of it and I told her I'd be back."

I asked a lot of people how they ended up in The Ardens. Nordheimer's story may have had more serendipity than the others, but it's typical in that it wasn't Arden's founding ideas that drew her there. Some people live in Arden because their parents did. Others just needed to be somewhere near Wilmington and happened to settle in the community. Some already knew the town for one reason or another—they had friends here, or came in to see plays—but weren't aware of its distinctive history. Ron Meick had been working in investments up in New Hampshire and decided he could live anywhere near an airport; he "zeroed in somehow on Wilmington" and bought a house in Arden. Eleven years later, he has retired from his old line of work and devotes his time to art and beekeeping.

What I didn't encounter was anyone who came here because he was deeply interested in the ideas of Henry George. I asked Barbara Macklem, a volunteer at the Arden Craft Shop Museum, how many bona fide Single Taxers live in The Ardens these days. "I would say there's a couple of dozen," she replied.

Yet Arden maintains its character. Its funds still come, with just a few minor exceptions, from the ground rent; its system of governance still rests on a mix of direct democracy and volunteerism. Nordheimer didn't move to Arden because she wanted to get involved in an alternative form of politics. Yet here she was in a committee meeting: six people sitting on a sofa and some comfy chairs, discussing ways they might spend money that someone has left to the community.

Arden is run by a collection of these committees: a Safety Committee, a Forest Committee, a Playground Committee, and so on. Four times a year there are New England–style town meetings, presided over by a town chair elected to a one-year term. (The current chair is Jeffrey Politis, a 46-year-old stay-at-home dad who has lived in The Ardens since 1999.) None of the posts are paid. Many people don't participate, but everyone is encouraged to, and the encouragement starts as soon as you move in. "Oh, they're like vampires," Nordheimer tells me. "They bite you the first day."

Utopia, Limited

Arden's founding fathers were Frank Stephens, a sculptor, and Will Price, an architect. They bought the farmland that became the town with a loan from Joseph Fels, a wealthy Georgist in the soap business; Price planned the fledgling village's unique layout but didn't actually live there, settling instead in the nearby arts-and-crafts community of Rose Valley, Pennsylvania. (The arts-and-crafts movement, which exalted traditional craftsmanship and denounced centralized industrial production, was a heavy influence on Arden in the early days too.)

Arden wasn't the country's only Single Tax colony. The Alabama town of Fairhope had been established on the same land-trust model in 1894, and several similar experiments were launched in the first few decades of the 20th century—enough for the Single Tax settlements to have their own baseball championship, which Arden won in 1923. But most were small projects that eventually faded away; only Fairhope, The Ardens, and an unincorporated New Jersey village called Free Acres survive today.

Homeowners in Arden purchased 99-year transferable leases to plots of land, and they were free to build pretty much anything they wanted there. (One early Ardenite decided to put his sleeping quarters in a treehouse.) Banks were initially reluctant to loan money to the colonists because of the village's unusual system of land tenure, so some townspeople created a building and loan association to finance their homes. (The B&L stayed active until the 1990s, when it dissolved on the grounds that no one needed it anymore.) Other necessities were provided by independent organizations. Some leaseholders created a club of volunteer firefighters, for example; others formed a private business to supply the town with water.

The trust also maintained roads and open space—even today, nearly half the town consists of forests and greens—and it balanced its laissez faire attitudes about people's houses and general behavior with strict restrictions on catching fish, shooting birds, and chopping trees. And it did its best to balance the books. Writing in The Libertarian, Florence Garvin greeted Arden's 25th fiscal year by noting with satisfaction that the town was now "without a public debt, except a $400 balance on the original land mortgage, which will be paid off the coming year."

The settlers established a rich and sometimes contentious cultural and political life. The cultural side was reflected by the town's networks of guilds—a Musicians' Gild, an Athletic Gild, a Gardeners' Gild, and so on—which sponsored sports, concerts, communal dinners, regular productions of Shakespeare's plays, and much else. On the political side were the town meetings, where women were voting years before that was allowed in the rest of Delaware. Indeed, Arden initially extended the franchise to everyone, even children.

The colony's political battles could be raucous, particularly when the trustees and the town meetings found themselves at odds. Residents who grew tired of the fights—or who thought even Arden's live-and-let-live rules were too restrictive—got an escape hatch in 1922 when Stephens and some others set up another land trust next door. This became Ardentown.

Ardentown is still thriving, but not all of Arden's spinoffs succeeded. One resident owned some land on the Choptank River in Maryland, and he tried to set up a Single Tax community there in 1927. The result was the tiny settlement of Gilpin Point, with about a dozen residents. Almost all of them came from Arden, and many, perhaps most, treated Gilpin Point as a vacation home rather than a primary residence; the colony dissolved after a decade. And then there was the original Ardencroft, not to be confused with the current town of that name. In 1930 a group led by Stephens set it up near Arden as a homestead community, with the idea that "until the present Depression blows over, they intend to raise their own food." They planted vegetables, issued their own currency, got in a fight with the mother village about whether Arden would chip in to help build a bridge, and fell apart after two years.

The state and county authorities mostly butted out. The only major change in the Ardenfolk's relationship with the government in those early days came in 1924, when the locals voted to establish their own school district. This was controversial among the Single Taxers, since it meant they'd be paying a new levy that wasn't based on Georgist principles; many of them preferred to educate their children privately or at home. (The line between "privately" and "at home" could be blurry—several Arden women operated their own home-based kindergartens for the community.) On the other hand, the new eight-grade Arden School meant that public-school students could be educated in an institution that reflected the community's culture.

At one point, reflecting that culture meant defying state law. The modern Ardencroft, organized as a nonprofit corporation rather than as a trust, was founded in 1950 to foster a more racially integrated community. Arden had always been open to everyone, but in practice the place was white; Ardencroft aimed to actively recruit residents of other races. The Ardens thus became one of the first desegregated school districts in any Jim Crow state, with the Arden School admitting its first black students at a time when the Delaware state constitution still mandated segregated public education. No one stopped them.

But the government was still there, and sometimes Ardenites would use it as a weapon in one internecine struggle or another. Usually this involved some petty dispute, as with George Brown's sex talk in 1911 or, five decades later, when some townspeople petitioned the county zoning board to prevent a gas station from being built on an Arden lot. Sometimes the issue was larger, as with a pair of lawsuits that pit a bunch of townspeople against the trustees in 1935 and 1942. In the first suit, the town's elected assessors tried to reduce rents, the trustees blocked the idea, and the government sided with the assessors, changing the balance of power within the village. In the second, a vacancy opened among the trustees, the town was deadlocked on whom to appoint, and the struggle got dragged into the courtroom.

During the latter battle, one of Frank Stephens' sons bemoaned the fact that their "communal problems" were now a matter for the courts, comparing the conflict to what he called the "futile madness" of World War II. The judge, for his part, got fed up with listening to what sounded to him like abstract ideological debates and decided to appoint the new trustee himself. As the man he tapped, one Phillip Cohen, left his chambers, the judge called after him: "Cohen, keep them out of my court!"

Roadz

But the most notable change in the community's relationship with the outside authorities came when it incorporated. An enclave that once had bordered on anarchism established a formally recognized government, and in the process it acquired a small but distinctly un-Georgist source of funds that did not come from anything like a land tax. The chief reasons for this change revolved around the roads.

It wasn't that the place lacked roads. The community had been maintaining its own private network of streets and footpaths since the beginning of the century. (To preserve those avenues' private status, the townspeople were required to close them off for a day once every seven years.) Incorporating made Arden eligible for state street aid, a fact that the advocates of incorporation were happy to tout. Still, the town certainly could have continued without the subsidy.

But amid those private paths there was Harvey Road, running straight through The Ardens. This was owned by the government, and the State Highway Commission had plans to widen it and to build an Interstate interchange. The locals strongly opposed this, and incorporating gave them a way to stop it: A municipality could claim exclusive powers of condemnation, then block any higher levels of government from taking property for the road.

And there was one more street problem. In the U.S., private associations generally have more flexibility than public authorities in setting their own rules. But thanks to a peculiar court decision in 1961, Arden suddenly found its hands tied when it came to enforcing its rules of the road. After a man ran a stop sign, Judge Robert Wahl decreed that the driver was free to do so because the state's motor vehicle laws had been written for public roads, not private ones. Arden had the power to kick a trespasser off its avenues, but that was it.

Not surprisingly, incorporation was highly controversial. When an early draft of the proposed town charter circulated, some residents warned that they could be erecting a mini-tyranny—an unaccountable body that lays sidewalks without a referendum, levies fines with no right of appeal, and drags offenders to the New Castle County Correctional Institution. The change was also opposed, interestingly, by at least some members of Delaware's political establishment. One of the local papers editorialized against incorporation on the grounds that it would create "just one more local government to be meshed into the whole when the time comes for giving this area the metropolitan government it needs." (A few years later, that same consolidationist spirit would shutter the Arden School.)

But the town voted to incorporate, and at the beginning of 1967 the Village of Arden became a municipality in the eyes of the law. Shortly afterward, the trustees transferred ownership of the roads to the town government. In 1973, they transferred the forests and greens as well, thus exempting the property from county taxation.

Ardentown and Ardencroft soon followed Arden's lead and transformed themselves into municipalities too.

The land trust continued as a private institution, albeit one intertwined closely with the local government. The trust collects rent from the town's leaseholders and, as the sole property owner, it pays everyone's county and school taxes. The rest of the rent goes to the municipal government. That bundle of money makes up the vast majority of the Arden budget—usually about 90 percent of it—though the town has a few additional sources of income, such as the rent for the antenna on the water tower (and, yes, the state's street aid). The county provides some services, and the rest are done either internally, as with the volunteers who run the local library, or by companies that contract with the village, as with the business that collects the trash. The big decisions are made in town meetings.

Outside the formal government there is a densely organized civic life. Much of this takes place under the aegis of the Arden Club, which serves as an umbrella for the town's guilds. Not all of today's guilds date back to Arden's early days, and not every guild from Arden's early days is still around. But one institution with deep roots is the Dinner Gild, a modern-day descendant of the communal meals the Ardenites enjoyed when the place was little more than a summer camp. Every Saturday night from October through May, one local group or another—maybe the Shakespeare Gild, maybe the Ivy Gables retirement home, maybe just a group of families that like to cook—prepares a big meal for anyone who wants to buy a ticket and come. Around 80–130 people show up for the supper, where they can enjoy their neighbors' company in an environment more convivial than a town meeting.

Dog Wars

"You know how every community has a wingnut or two?" Ken Rosenberg tells me as he sets up some audio equipment. "We have several."

I'm back in the Buzz Ware Village Center, where Ardencroft is holding its May town meeting. I'd been warned about Ardencroft politics. Every small town has its fights, but in this one, I was told, the battles had gotten unusually nasty lately.

Pat Morrison, a retired doula, had regaled me the day before with some stories about the sniping. "We had some dog problems," she had said. "One person in town was convincing these other people that they didn't have to leash their dogs." Some pit bulls started scaring kids and hurting other dogs, "and I happened to be on the Safety Committee at this point. I thought we were supposed to try to get them to stop unleashing their dogs. But there was this counter group that wanted freedom: 'Dogs should have freedom.' It became huge. It blew up over three or four years to threats against people's lives."

That struggle mixed with other conflicts, and the 2015 election for town chair was bitterly contested, complete with accusations of vote fraud. The new chair—Ken Morrison, Pat's husband—hired a parliamentarian to bring some order to the town meetings. He paid a couple of county cops to be on hand too, just in case things got violent.

Things seem to have wound down a bit in the last two years, though. Neither the parliamentarian nor the police are here tonight. Turnout in general is pretty sparse, and tensions are mostly limited to some passive-aggressive comments from a woman who, I eventually learn, was one of the losing candidates for chair in 2015.

The closest things come to boiling over is when the talk turns to signage. I won't bore you with all the details, but the upshot is that there's a spot in Ardencroft where it isn't entirely clear which house number goes with which house. At the last meeting the town voted to improve the appropriate signs, so that there won't be delays when someone has to respond to an emergency. But now the Safety Committee has looked into the issue and come to a different conclusion. If there's a problem, they say, it's not the signage. It's the fact that three different houses close to each other are all numbered 1502, each for a different street. Amy Pollock—the woman who lost the election two years ago—won't have any of it: She wants new signs. No one hurls any insults, but more than one voice starts to drip with contempt.

And then it's on to other business. Ardencroft has six town meetings a year, while Arden and Ardentown each have four; there's a proposal afoot to reduce the Ardencroft meetings to four as well. One citizen stands to object: "If you want to live in Arden, move to Arden!"

The Master-Planned Free-for-All

The stereotypical suburb is a comprehensibly planned place whose rules foster uniformity. But not every settlement surrounding a city fits that model. In 1978 the geographer Roger Barnett identified a type of community he called the "libertarian suburb": subdivisions where, due to various hiccups in the history of the local land market, lots were developed individually, in an improvisatory manner, rather than en masse by a single developer. The result is a landscape of dramatically different houses, irregular lot sizes, and diverse yards: "a patio with exotic plants and garden furniture; a vegetable plot; livestock raising, including the rearing of sheep and horses; overflow storage from the house; auto repairing; auto dismantling."

There is one political issue in such places that is "guaranteed to provoke concerted reaction," Barnett says: "Incorporation means submitting to minimum standards and paying for improvements required by municipal regulation. Who needs sewers, wide streets, sidewalks, and a code that renders 'home improvements' subject to visits and approval from building inspectors?"

Barnett focused on certain suburbs of Stockton, California, but another academic, Jacob Wegmann, has described a similar pattern in some working-class communities near L.A.—places whose residents "found plots that they could afford to buy, living on them cheaply in tents, shacks made of boxes or tar paper, or trailers, while gradually building their houses, sometimes over many years, without debt." They worked for wages when they had to and for themselves to the extent that they could; many of them fended off annexation by incorporating "municipal governments so small that they governed territories closer in scale to neighborhoods than to typical small cities." Most of those micro-town governments' functions were then contracted out.

That's a radically different form of suburban living than you'd find in those master-planned developments. Yet Arden somehow manages to echo both models at the same time.

Will Price designed Arden comprehensively, aiming to emulate the English planner Ebenezer Howard's utopian ideas about "garden cities." Yet within the highly planned framework of Price's landscape, the town allowed an enormous degree of unplanned freedom. Self-built homes were common. People developed their own lots with little standardization, and not always with respect for the county codes. The late Wilmington News-Journal columnist Bill Frank once described Arden architecture as "a strange collection of homes, ranging from fine buildings to shacks, from comfortable old English-type structures to expanded chicken coops." The town is a master-planned free-for-all.

Arden isn't just reluctant to impose its own land-use rules. It has wrangled official exemptions from a number of county regulations too. New Castle County restricts how high your grass can grow, but those rules aren't enforced in Arden, where several of the locals keep natural gardens. When the county adopted "instant ticketing" for property code violations, Arden opted out. Ardenites are also allowed to ignore several rules restricting home-based businesses, and as a result there are a number of studios, workshops, and other enterprises in the village.

Not every business blossoms in Arden. There's a dearth of shops in the town—"That is our major downfall," Macklem the museum volunteer says with regret—and while various inns and eateries have existed there in the past, today any Ardenites who want to go out to dinner have to exit the village limits. But if you want to open a restaurant in Arden, you're allowed to try.

Those looser legal rules reflect a looser culture. In Arden, unattended kids roam the roads and forests freely, a fact that wouldn't have seemed unusual in my 1970s childhood but can be jarring to outsiders today. Macklem once was giving a tour of the town to a group of students from Temple University when they ran into a 10-year-old and a 12-year-old coming home from a basketball game. The children said hello and Macklem said hello, and they chatted a while before everyone moved on. The visiting students seemed nonplussed by the exchange. "The kids are out without adults," they said. "They talked to you."

"The idea that children could be out without a parent hovering was just completely unknown to them," Macklem recalls. "And the fact that the kids talked to someone who they obviously knew but who was not a parent."

Jollity Farm

Such differences don't always endear Arden to outsiders. The place has always attracted strange rumors—there were tales in the early days that it was a nudist colony, and more recently there have been conspiracy theories that paint the town as a Satanic haven for the Illuminati. Macklem sometimes encounters less outré forms of resentment. "Our reputation is of being different," she says, "which can be a condemnation from people. 'People in Arden get their own way.' 'People in Arden do whatever they want.' 'People in Arden are just really kind of strange.'" As I was working on this article, I asked a friend from Wilmington what sort of reputation the town had when he was growing up. "Pretentious and weird," he replied.

But the place also has far more admirers than your average small suburb. People come from all over the area for concerts at the Gild Hall, for plays on the Village Green, for the annual Arden Fair. Many of those visitors like what they see. Some like it so much that they move there. The town's slogan is "You are welcome hither," and there doesn't seem to be a shortage of people willing to take the offer.

In Radical Innocent, his biography of Upton Sinclair, Anthony Arthur compares the George Brown affair of 1911 to the events of Nathaniel Hawthorne's story "The May-Pole of Merry Mount," in which Puritan authorities invade a free-spirited settlement to suppress its festivities. Arthur gets the chronology of the Brown tale wrong, making the parallels a little less striking than he supposes. But he may have been onto something anyway. There really was a freewheeling little outpost in early Massachusetts called Merrymount. The people there defied the Puritans' economic rules by selling rum and guns to the Indians, and they defied the Puritans' moral rules by restoring the traditional May Day revels. "Jollity and gloom were contending for an empire," Hawthorne wrote, and Merrymount was the capital of jollity.

After the Arden 11 did their time for those illicit acts of baseball and ice cream, Sinclair claimed that the constable who dragged them to the pen kept saying "that we were just the jolliest, jolliest bunch of convicts he had ever, ever put in jail." More than a century later, Arden is more gentrified and more governed than it was in those anarchic early days. But something jolly is still alive there.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Delaware's Odd, Beautiful, Contentious, Private Utopia."

Show Comments (28)