You Should Read More Romance Novels

The libertarian case for bodice rippers

Libertarians like their genre fiction just fine and read lots of it. Science fiction is a staple, from Ayn Rand's Anthem to the works of Robert Heinlein to Joss Whedon's dearly departed television series Firefly. Murray Rothbard is on record as a reader of detective novels. Rand praised Ian Fleming and Mickey Spillane for the rough heroism of their potboilers. Rose Wilder Lane's and Laura Ingalls Wilder's independence-minded stories of settlers on the frontier have been staples of children's literature for generations.

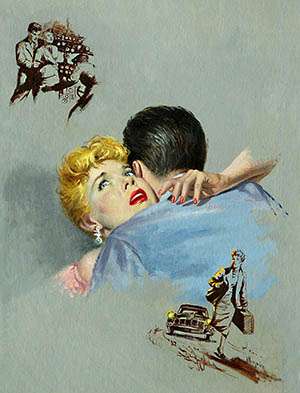

But when it comes to romance novels, it seems as if fans of the free market aren't buying what Fabio is selling. Hayek isn't on record anywhere as a fan of Gone With the Wind. And Coase and Mises are strangely silent about the charms of regency romances and modern gothics. Maybe it's the lurid covers, with their heaving bosoms and metallic lettering? Maybe there's something to the stereotype of libertarians as emotionless rational calculators? I prefer a third thesis: Maybe libertarians just don't know what they're missing under these covers.

In fact, modern romance fiction is filled with lessons about the things independent thinkers value—or ought to value—most highly. If you're a reader looking for novels that understand the importance of work and markets, that promote the bourgeois virtues, and that enthusiastically support Millian experiments in living, you should be reading romance.

'If I Could Make a Living Out of Loving You'

The basic structure of most romance novels is not terrifically complicated. The hero and heroine are introduced to the reader and one another very early on. As savvy readers know, even if the protagonists claim to despise one another, they are destined for a happy ending by the novel's final pages. So the job of the romance author is to throw a compelling obstacle in their way.

Sometimes the obstacle is a past insult (like Mr. Darcy's famous snub of Elizabeth Bennett early in Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice). Sometimes it's a tortured past (such as Mr. Rochester's mad first wife, locked in the attic at Thornfield Hall). Really, the thwarting device can be anything—an overly protective older brother, a difference in class status, a run of incredibly bad timing, a poorly chosen outfit, a cursed demon amulet. It just has to keep the hero and heroine apart for enough tantalizingly torturous pages to make the happy ending feel satisfying and earned.

What's interesting, though, is how often the obstacle is work. While Fifty Shades of Gray has made us all annoyingly familiar with the "mysterious billionaire" subgenre of romance novels, in which the hero has a seemingly endless supply of wealth while apparently doing very little to obtain or maintain it, other romances manage the realism somewhat better.

Melia Alexander's Merger of the Heart, for example, begins with the heroine's discovery that her grandfather died moments before selling the family construction business out from under her. The hero is, of course, the man who was ready to buy it. Conflict ensues.

What's great about Merger of the Heart is that we hear the details of the heroine's business. She's anxious because Grandpa purchased construction equipment rather than leasing it and wasn't able to pull in enough work to break even with the cost. She's worried about the fates of her 200 employees. Throughout the novel we consistently see her thinking about and working on the company on a daily basis.

The trouble with Merger of the Heart, though, is one that plagues "contemporaries," or romance novels set in the current time. The company that wants to buy our heroine's family construction business seeks it to raze the corporate offices, get the zoning changed, then redevelop the valuable riverfront property. The heroine protests because of her emotional investment in the business. It's a familiar cliché, and it's as present in contemporary romance fiction as in popular culture writ large: The big company is always the bad guy, and the hero who works for the big company only achieves redemption and wins the heroine's heart when he realizes that mom-and-pop shops are more important than big, faceless corporations. Atlas Shrugged it ain't.

So I greatly prefer the complicated and nuanced discussions of work that can be found in historical romance novels. (These are the ones with the bare-chested heroes and corseted heroines.) Often set among the aristocracy, these tales can lead to some interesting debates over gender roles ("You get to have an interesting job and I have to learn to embroider? How is that fair?" or "Do you really expect that I'll give up working when we get married?") or the mixed blessing of aristocratic privilege ("My father gambled away the family fortune, so I must work, but I have no skills!" or "I'd really like to be a writer/scientist/architect, but it is simply not done by people of my class.") or class and opportunity ("Yes, I stole your wallet, but I was fired from my job as a governess for 'tempting' the master of the house, and isn't it better to steal than to be a prostitute?"). Because of the deep conflicts over work throughout history, work in a historical romance novel can be a source of conflict between the hero and heroine. And romance novels thrive on conflict that keeps the lovers deliciously apart until they find a way to reach a happy ending.

In Sabrina Jeffries' How to Woo a Reluctant Lady, our heroine Minerva is a gothic novelist who wants to arrange a fake engagement to an inappropriate man in order to encourage her grandmother to release her inheritance. (The basic plot of the romance may be simple, but there are endlessly delightful variations and rococo complexities to discover.) What Minerva finds, instead, is a lawyer and fanboy: "I've read them all," he says of her books. "When she's with people she hides behind her clever quips and her cynical views, but you can see the real Minerva in her novels. And I like that Minerva."

His genuine affection and respect throws Minerva for a loop and she finds that she doesn't hate him after all. But here comes the mandatory obstacle: She believes their professions mean she can never have him, since a king's counsel requires a wife of pristine reputation and she could never be that. She could never play the part of adoring spouse exclusively, and he would come to resent her need to write. Two hundred pages later they've found a way to continue both their careers and their romance.

The heroine of Laura Kinsale's Midsummer Moon is an inventor of flying machines. Her suitor must learn that trying to keep her safe by forbidding her to work on and test her machines is as damaging to her as any physical injury. The heroine of Tessa Dare's A Week to be Wicked is a geologist who is desperately trying to get her newly discovered fossil specimen to Edinburgh for a symposium. The Duke who comes to her assistance learns to love her for her academic passion, even as he helps her attain her professional goals. Violet Waterford of The Countess Conspiracy by Courtney Milan has used Sebastian Malheur as the beard for her botanical research for years. When he decides he can't play along any more, it forces her to claim her work in public and face her attraction to him. And in Linda Mooney's Mine Until Midnight, the hero and heroine pause in the middle of an exhibit at the Crystal Palace to debate creative destruction, technical advances in agricultural machinery, and the question of whether a workforce will move from the country to the city. (Shortly afterwards they make out passionately in a secluded corner.) In all these stories, the characters' passion for their work is at least as important as their passion for each other.

My favorite discussion of work, however, happens in Loretta Chase's Silk Is for Seduction. Here, the Duke of Clevedon must learn to appreciate and even participate in the bourgeois virtues of the dressmaker heroine, Marcelline Noirot. Her job, he points out to her, "isn't employment. It's your vocation." They begin working together, combining his connections and her talents. By the end of the book, they have gotten into business, and into bed, together.

In romances like these, appreciating a heroine's occupation means appreciating the heroine. A woman who is free to be herself in her working life is free to be herself in her romantic life. And no happy ending is possible without that.

'I Honestly Love You'

But romance novels don't just offer hot occupational action. They provide more subtle lessons as well.

Trust and the keeping of promises are, as economist Deirdre McCloskey's work has argued, important virtues for preserving the kind of culture that allows market economies to function. They are also central to the plot of many romance novels.

In Courtney Milan's Unlocked, for example, Lady Elaine Warren is teased and tormented as a young woman by the Earl of Westfield and his society friends. He returns to London years later, older and wiser, and must persuade her that he has changed and that he is worthy of her trust. In fact, the entire series of four books set in and around Lady Elaine's group of acquaintances is an extended meditation on how we learn to trust people and what it means when we do.

Romantic suspense novels often turn on questions of trust as well. From The Scarlet Pimpernel onward, the secret agent has been an irresistible romantic hero—and sometimes heroine. Lauren Willig's wildly popular Pink Carnation series is a round dozen of novels playing with the question of how to trust people whose very occupation requires them to lie.

Contemporary romantic suspense novels often feature undercover cops, or witnesses with shady pasts, or romantic leads who are (for a time) suspects in serious crimes. The first novel in Suzanne Brockmann's Troubleshooters series, The Unsung Hero, features a Navy SEAL recovering from a head injury who spots a terrorist. When the Navy dismisses his concerns as paranoia caused by the head trauma, he needs to find other people who will trust his instincts. The novel's heroine, a doctor, initially agrees with the Navy's diagnosis, but comes to trust him over time. Together they track down the terrorist and find a happy ending.

The point is that romantic exchanges, like economic exchanges, require trust. They require that the two people most intimately involved in the exchange completely trust one another—even if they trust no one else. So when Marcelline of Silk Is for Seduction tells her duke that she cannot marry him because "You couldn't ally yourself with a worse family. We seduce and swindle, lie and cheat. We have no scruples, no morals, no ethics. We don't even understand what those things are," he responds, "You don't cheat your customers." And any reader with a grain of sense knows that means he trusts her entirely.

'She's a Very Kinky Girl'

But let's be honest, a lot of readers are just in it for the naughty bits, right? There's certainly plenty of sex in the modern romance novel, and—for reasons both prurient and pure—libertarians may be particularly interested in how sex works in the genre these days.

Leaving aside a few notable exceptions (Fifty Shades of Gray, in particular) most modern romance novels make a feature out of the sexiness of consent. In Beyond Heaving Bosoms, a study of the romance novel, Sarah Wendell and Candy Tan note that romances written in the '70s and '80s routinely featured scenes where the hero raped the heroine, who then came to realize how much she really loved him. Today's readers won't stand for this, and "when books featuring rape or forced seduction scenes rear their tumescent, purple-helmeted heads, Internet message boards on Romance websites light up like Christmas trees, with the majority of people expressing indignation at the continued presence of this spectre in our genre."

Writers like Courtney Milan are often singled out for particular praise for the care and eroticism with which they handle consent in their novels. When Sebastian and Violet finally go to bed together in The Countess Conspiracy, the whole encounter is infused with concern for Violet (who was abused by her first husband) and for her continued consent. Pantingly, they reach an agreement about contraception. While deftly unbuttoning her bodice and unlacing her corset Sebastian tells her, "Stop me…Stop me any time you wish—" Her response: "I don't." Their foreplay is a model—and a very sexy one—for a sane and adult approach to the fraught topic of sexual consent.

Steamy though they are, the sex scenes in Milan's novels are fairly traditional. The whole-hearted embrace of kink by other romance novelists, however, means that the modern romance novel might well take its motto from John Stuart Mill's On Liberty. "There should be different experiments of living…free scope should be given to varieties of character, short of injury to others;…the worth of different modes of life should be proved practically, when anyone thinks fit to try them." Whatever romantic or erotic interest a reader has—heterosexuality, bisexuality, homosexuality, BDSM, threesomes, moresomes, vampires, aliens, threesomes with vampires and aliens, angels, demons, werewolves and other werecreatures in their human or animal forms—there is a romance novel out there for the reader who wants to read about it. And in nearly every case, those desires are treated, by everyone but the novels' worst villains, as understandable, acceptable, and perfectly OK.

Such complete acceptance of sexual choices in life is a fantasy, of course, but it's a great one, and a particularly libertarian one at that. The point of the romance novel is not that everyone should have sex with three werewolf lovers beneath the light of the full moon, but that all people should have the chance to make their own decisions and fully live the lives they choose.

The Book of Love

Romance novels are a billion-dollar industry, making up about 13 percent of the total market for adult book and electronic book purchases. Liberty-minded folk owe it to themselves to crack open a few of these bestsellers, consider what values the bodice-ripper reading populace is imbibing, and ponder what these novels can tell us about the world we're living in. If nothing else, the genre is an underappreciated vector for teaching the value of work, the importance of trust and other bourgeois virtues, and the individual's right to choose his or her own life. No matter who you love or how you love them, you've got to love that.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "You Should Read More Romance Novels."

Show Comments (63)