President Obama's Clemency Project is a Bureaucratic Nightmare

The slowness and disorganization of the clemency process put in place has stranded many of the prisoners and families it was supposed to help.

Last Friday, President Obama commuted the sentences of 42 federal inmates, bringing the total number of sentences commuted by the president to 348.

While this is certainly something to celebrate, especially for the families of those inmates who were scheduled to spend the rest of their lives behind bars, these inmates make up only a fraction of the 10,000 or so prisoners former Attorney General Eric Holder projected would be eligible for clemency under the administration's clemency initiative, which kicked off in April 2014. The initiative aims to prioritize clemency applications from inmates who met certain criteria, such as those who are non-violent, low-level offenders without significant ties to large scale criminal organizations, gangs or cartels, and individuals who have served at least 10 years already.

But instead of offering salvation, the painful slowness of the clemency process has subjected many prisoners and their families to a new kind of bureaucratic cruelty as they wait in dimming hope of being amongst the lucky few who make it through the system.

One such inmate is Antonio Bascaro, who according to clemencyreport.com is the longest serving prisoner for a marijuana offense. Bascaro was sentenced in 1982 to 60 years in prison for a series of crimes tied to a large marijuana conspiracy in the late 70s, when Jimmy Carter was president and before President Reagan ramped up the harsh sentences associated with the "War on Drugs."

In 2014, the United States Sentencing Commission (USSC) voted to amend its sentencing guidelines to make sentences for most drug offenses shorter—and also made the new rules retroactive.

However, because Mr. Bascaro was sentenced in 1982, two years before the USSC was created, a court ruled he was not eligible for a reduction in his sentence under the amended guidelines.

At this point, then, Mr. Bascaro's only hope at an early release is to be granted clemency before President Obama leaves office, or to survive past his release date, which is currently June 8, 2019. At that time, he will be 85 years old.

The initiative was sold as a way of helping inmates like Bascaro. Instead, he's become the victim of a slow-moving system that has struggled to live up to its goals.

When the initiative was launched, the Office of the Pardon Attorney announced it would be working with the Federal Bureau of Prisons to facilitate the initiative, as well as with the Clemency Project 2014 (CP14), a group composed of the American Bar Association, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, the Federal Defenders, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM).

Clemency Project 2014 recruited over 4,000 volunteer lawyers to screen applications from federal prisoners looking to obtain counsel to complete their clemency petition. After inmates are screened and CP14 determines their case meets the president's criteria for clemency, the petitions are sent to the Office of the Pardon Attorney at the Justice Department. The Office of the Pardon Attorney reviews the cases it's sent through CP14 and those submitted by inmates directly. The U.S. Pardon Attorney then decides which cases to send to Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates for review. Yates decides which cases make their way to the White House counsel, who then has the final say over which applications make their way to the President's desk.

With an undertaking this large, and a bureaucratic structure this vast, the system has struggled to process applications in a timely manner. A Politico investigation published in January 2015 found that the clemency initiative "languished during its first year due to a flood of applications, inadequate resources, reliance on a group of outside lawyers to prepare prisoners' paperwork, and a series of bureaucratic hurdles that weren't anticipated."

In January 2016, Pardon Attorney Deborah Leff announced she was resigning barely one year after she was formally appointed to the job. In her resignation letter to Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates, Leff wrote that the Justice Department had "not fulfilled its commitment to provide the resources necessary for my office to make timely and thoughtful recommendations on clemency to the president." According to USA Today, "Leff said Yates had overruled her recommendations in an increasing number of cases—and that in those cases, the president was unaware of the difference of opinion. " After her departure, a longtime federal prosecutor, Robert A. Zauzmer, was appointed to fill her shoes.

Since Leff's departure, the Office of the Pardon Attorney remains overwhelmed. In January, the office only had 10 lawyers, which The New York Times noted is "virtually the same size it was 20 years ago," despite the fact that the number of clemency petitions has increased substantially.

According to Kevin Ring, Vice President of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, a founding member of CP14, Obama's effort was beset with problems from the very beginning. "All the usual problems are there. Prosecutors are reviewing prosecutors decisions and don't necessarily want to let people out—they're not the most sympathetic crowd," Ring said. "Even beyond that, he frankly didn't have the resources to do this job. That's why we got involved with CP14 to provide free legal services."

"From all accounts of what we've heard, the president is personally engaged in this issue," Ring said. "I think the problem isn't lack of will, but the lack of infrastructure."

Early this year, the Office of the Pardon Attorney announced it was hiring 16 new attorneys, which would bring the total number of lawyers in the office to 26.

With 10,621 commutation petitions pending at the Office of the Pardon Attorney in May, and only 26 attorneys available to review, this means that each staffer is responsible for thoroughly reviewing roughly 408 petitions each over the next 6 or so months before Obama leaves office. And the petitions lucky enough to get vetted through the first stage have to endure the bureaucratic vetting process in place before eventually landing on the president's desk.

Separately, as of June 2, CP14 has sent only 1,150 petitions to the Office of the Pardon Attorney for review. The rates of success aren't great. According to Cynthia Roseberry, project manager of Clemency Project 2014, 145 petitions CP14 has sent the Office of the Pardon Attorney "have been acted on," which means they've either been granted or denied by the President, and 111 have been granted. With time running out, many inmates and their families are left wondering if their cases are going to fall through the cracks.

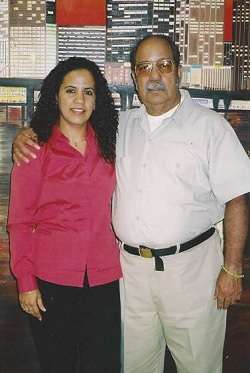

That's the position in which Bascaro and his family now find themselves. According to his daughter, Aicha Bascaro, the clemency process has been a bureaucratic mess for him and his family. In a phone interview, Aicha said her father applied for assistance through CP14 in May 2014. It wasn't until October 2015 that they were assigned a lawyer. In May of this year—two years after he initially applied—Aicha was told that her father's lawyer was withdrawing himself as representation of his case.

According to the letter, the lawyer writes: "He deserves clemency, as he has been in jail for more than 35 years for marijuana smuggling, and he's over 80 years old. Unfortunately, I am a sole practitioner with no criminal law experience, and I do not have the time or the resources to devote to this matter, which is far more complicated than I initially anticipated."

After Aicha received that letter from the lawyer, who sent it to her as a courtesy, not a requirement, Aicha emailed CP14 directly. Aicha told Reason, "I got a response on May 16 that said they are personally reviewing the case to see if he qualifies for representation."

"My father doesn't have a lot of time left. He's had back surgery last year and now walks with a cane. He also has glaucoma."

When I asked Roseberry if she had seen many lawyers withdraw as representation, she told me it happens infrequently, and that most lawyers have stayed. No exact figures were cited, though.

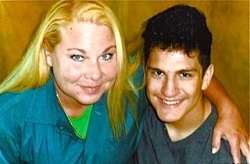

Other inmates, like Rose Summers, have had their cases closed by CP14 because of their upcoming release dates. Summers, a nonviolent drug offender, was sentenced to over 24 years in prison in 1997 when her son was just one year old. Her release date is August 2018.

When I asked Roseberry why they had closed cases of inmates because of their release dates, she said: "We have decided that our focus is going to be on the longer sentences and work our way back." She continued, "we have a skeletal staff, and the best use of our resources is to focus on lifers and those who have still have 40, 30, 20 years left."

For the next six or so months, families of inmates will have to keep their fingers crossed that the see a familiar name on the list of inmates granted clemency appears on the White House's website seemingly random days at a time.

At this pace, it seems likely that Obama's clemency initiative will benefit few, while the majority of otherwise eligible inmates will remain behind bars—waiting and hoping that the next president offers the chance at freedom that Obama's clemency project was supposed to give them.

This article has been updated.

Show Comments (33)