Learning from 1896: Why an Anti-Trump Third Party Will Flop

History shows the flaws in temporary 'fixes' against populist takeovers.

If the anti-Trump third party plotters want a clue on how they might fare, they can learn from events in another realigning presidential election. Many elements of the story are familiar. Populist insurgents, often backed by low income new voters, seized control of one of the two major parties. Though caught completely off guard, the toppled elite and activists of the original party eventually fought back. They united in a third party intended to be the "true" embodiment of the old. They nominated two prominent politicians and generated substantial media coverage and praise, including from the last standard bearer of the old party. Despite this, the new party was a bust in November, garnering less than one percent of the vote.

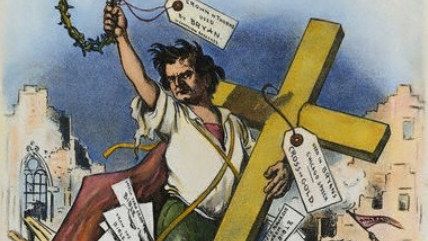

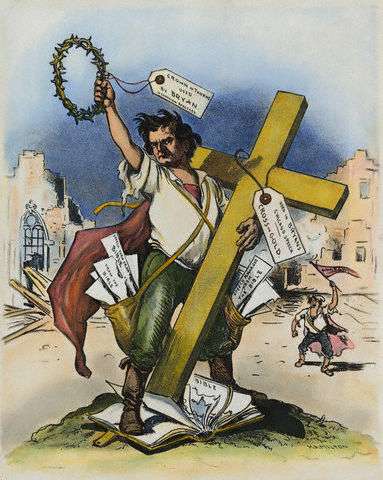

These events, though dating to more than a century ago, should give pause to advocates of an anti-Trump third party. In 1896, the old leadership of the Democratic Party had watched in horror as a group of outsiders, led by the young and charismatic William Jennings Bryan, captured the national convention and jettisoned the party's traditional support of the gold standard. Bryan charged that past Democratic policies had destroyed American jobs, compromised U.S. sovereignty, and enslaved the U.S. to British economic interests. Rhetoric on all sides was toxic and no reconciliation appeared possible. Democratic Senator Benjamin Tillman, one of the best known of these "Popocrats," even promised to skewer the pro-gold Democratic sitting president, Grover Cleveland, with a pitchfork. Bryan went on the hustings speaking to large and boisterous crowds about how a "cross of gold" was crucifying mankind.

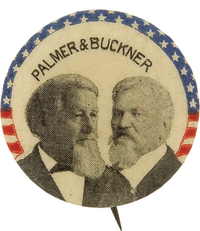

Once over the initial shock, anti-Bryan's Democrats expressed determination to never support either him or the Republican alternative, William McKinley, who, though a recent convert to a strict gold standard, championed the protectionism they had long abhorred. They formed the National Democratic Party (NDP), drafted a pro-gold standard platform, and nominated two former governors. The rebels were a diverse coalition of party regulars, such as Senators William Vilas of Wisconsin and Donelson Caffery of Louisiana, former Mayor John P. Hopkins of Chicago, former U.S. Representatives William D. Bynum of Illinois and William C.P. Breckinridge of Kentucky, as well such pro-gold/pro-free trade ideological pundits as Edward Atkinson and Oswald Garrison Villard.

Many of the contradictions that characterized the NDP are already appearing in the nascent anti-Trump third party. Among these is an emerging tension between advocates of building a permanent party to replace the GOP, such as Randy Barnett, a professor at Georgetown Law School, and those who, in the words of Bill Kristol, want a "one time, emergency adjustment" allowing voters "to correct the temporary mistake of nominating Trump."

Using rhetoric much like current anti-Trump third party advocates, former governor John M. Palmer, the NDP's presidential candidate, hoped to create a "nucleus around which the true Democrat….can rally once more, and to preserve a place for our erring brothers, if the time comes when they repent." Revealingly, Kristol suggests the "Latter Day Republicans" as the party's name. The rebels of 1896 had much the same idea in selecting "the National Democratic Party" as their brand.

A major flaw in both the Kristol, and to some extent, the Barnett strategy is already apparent. The stated goal of splitting a major party just to defeat its official candidate clashes with the natural desire of voters in that party to not throw away their votes or help the candidate in the party that remains united. In October 1896, for example, one NDP activist, expressing a widely shared frustration, reported that many Democrats were "almost persuaded" to vote for Palmer "but hesitate at the fear that the National Democracy is but a Republican side show." Not surprisingly, Bryan's supporters had a field day depicting the campaign as giving aid and comfort to the GOP and Palmer regularly was met by hecklers with jeers such as "Look at the McKinley Aid Society." It makes perfect sense to assume that supporters of anti-Trump third party will face an equal measure of hostility, or worse.

Another likely vote-suppressing factor for an anti-Trump party is the thorny issue of how to deal with down-ticket candidates. The NDP ran these candidates in only a few states, almost all against anti-gold Democrats. More typical was the policy adopted in Wisconsin at the behest of Vilas to abstain entirely from non-presidential races. Vilas asked whether "the fight should be hot? We are after votes now, and the unification of the party by and by." An unintended consequence of Vilas's conciliatory approach toward incumbent Democrats was to turn off potential voters who concluded that the NDP was not a serious political party.

Thus far, proponents of an anti-Trump third party are echoing much of this approach toward down-ticket races. One significant difference with 1896 is that more restrictive ballot laws now make running such candidates pretty much a non-starter, at least for this election. Barnett depicts the new party as a "vessel" that GOP non-presidential candidates can "support in good conscience." Talk show host Erick Erickson argues that it will actually help these candidates by increasing Republican turnout. "If voters don't turn out to vote for a presidential candidate," he asserts, "they're probably not going to turn out and vote for state and local legislative races as well, which could be a real bloodbath for Republicans." The likely result, however, will be to feed the perception that the anti-Trump party is just a feel-good temporary refuge for Republicans to temporarily park their votes, or a spoiler for Hillary, not a credible third party.

The diverse nature of the anti-Trump third party plotters creates an added problem. The bolters of 2016 are an amalgam of neo-conservatives, social conservatives, fiscal conservatives, quasi-nativists, moderates, and even some small-government libertarians and constitutionalists. Finding a candidate who can appease, much less energize, all of these factions may be difficult. By contrast, the NDP, despite its eventual failure, had a much easier task of uniting its members around two simple goals: preserving the gold standard and low tariffs.

While an anti-Trump third party, as currently conceived, will probably fail, and fail badly, a third party organized along different lines might just make a splash. The trick is to mount a campaign that can simultaneously appeal to the record numbers of disaffected Republicans and disaffected Democrats. The current plan of anti-Trump party proponents, such as Erik Erickson, to target political and social conservatives, including GOP foreign policy hawks, pretty much closes off the prospect of getting non-Republican votes. A better way to create a winning combination is to run a candidate who can reach those socially liberal voters in the Democratic Party who reject Hillary and her crony capitalism and hawkishness but aren't necessarily comfortable with Sanders' socialism. Right now, the only candidate who could conceivably pull this off is Libertarian Gary Johnson, a successful former two-term governor of New Mexico who will have ballot status in nearly all states.

Because of his commitment to civil liberties and free markets, his opposition to the drug war, and his call for a more non-interventionist foreign policy, Johnson has a once in a lifetime opportunity to peel off disaffected elements from both parties. Both the Barnett and Kristol strategies, by more or less limiting the pool to conservatives who would normally vote GOP, can't hope to do this. Of course, it would be a pipedream to believe Johnson can win but he may be able to make major inroads and send a message that voters reject the corrupt Democratic establishment of Hillary and the impulsive xenophobia of Trump. All of this also assumes not only the Johnson is up to the task of staying on message and has sufficient funding to bring that message to the voters.

Show Comments (58)