The Measles Outbreak and the Precautionary Principle

How U.S. public health authorities helped fuel the anti-vaccine movement

In 1998, the British researcher Andrew Wakefield and 11 co-authors published an article in the prestigious journal The Lancet claiming that 12 children had experienced the onset of severe neurological disorders shortly after being inoculated with the combined measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine. Wakefield's paper sparked widespread hysteria about the possible connection between the vaccine and autism. The study was ultimately discredited, and the journal retracted it in 2010; Wakefield has now lost his medical license for dishonesty and unethical practices.

Meanwhile, in the wake of several widely publicized methylmercury poisoning incidents, the FDA Modernization Act of 1997 included provisions directing the Food and Drug Administration to assess the safety of all mercury compounds in any of the products it regulated. Tiny amounts of thimerosal, an anti-bacterial compound that breaks down into ethylmercury in the body, were included in several products, including eye drops, nasal sprays—and some vaccines. The FDA had just launched its inquiry into mercury containing products when Wakefield's article appeared.

In April 1999, the FDA asked vaccine manufacturers for data on the amounts of thimerosal contained in their formulations. In July of the same year, the United States Public Health Service and the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a joint statement declaring that "thimerosal-containing vaccines should be removed as soon as possible." The statement noted that "there are no data or evidence of any harm" stemming from the minuscule amounts of thimerosal in the vaccines, but the authors nonetheless recommended removing the preservative "because any potential risk is of concern."

The underlying notion here is known as the precautionary principle. The canonical version of the precautionary principle—the "Wingspread Consensus Statement"—was framed by a group of environmentalists in 1998. "When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment," it said, "precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically." In its 2001 analysis of the safety of thimerosal, the Institute of Medicine explicitly cited the Wingspread statement to justify the removal of the preservative from childhood vaccines.

This invocation of precaution by public health officials and physicians quickly attracted the attention of autism activists who swiftly forged a connection between thimerosal in vaccines and autism. In 2000, two of those activists—Sallie Bernard and Lyn Redwood—co-founded the group Safeminds and began promoting the idea that autism is a novel form of mercury poisoning. Safeminds continues to push this idea, even as more recent studies find no connection between autism and the preservative.

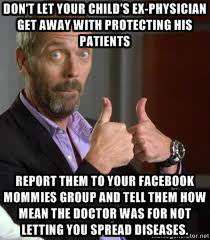

As the fear that inoculations could cause autism spread to the wider public, it became a staple in the anti-vaccination movement. Many concerned parents reasoned that if public health officials are worried about the safety of vaccines, they should worry too.

Even though the Wakefield study has been thoroughly invalidated, with several scientific reviews conclusively debunking the supposed vaccine/autism connection, a YouGov poll in January found that some 13 percent of Americans believe that childhood shots can definitely or probably cause autism. Dishearteningly, the most credulous group is the youngest—adults aged ages 18 to 29—where 21 percent embrace the idea.

In that way, a "precautionary" measure a decade and a half ago helped kindle the current outbreak of measles. Public health officials thought it was a case of "better safe than sorry," but the consequences left us more sorry than safe.

Show Comments (182)