How the Tax Code Manipulates Us

Every time tax rules nudge us in a chosen direction, they preempt the market's signals.

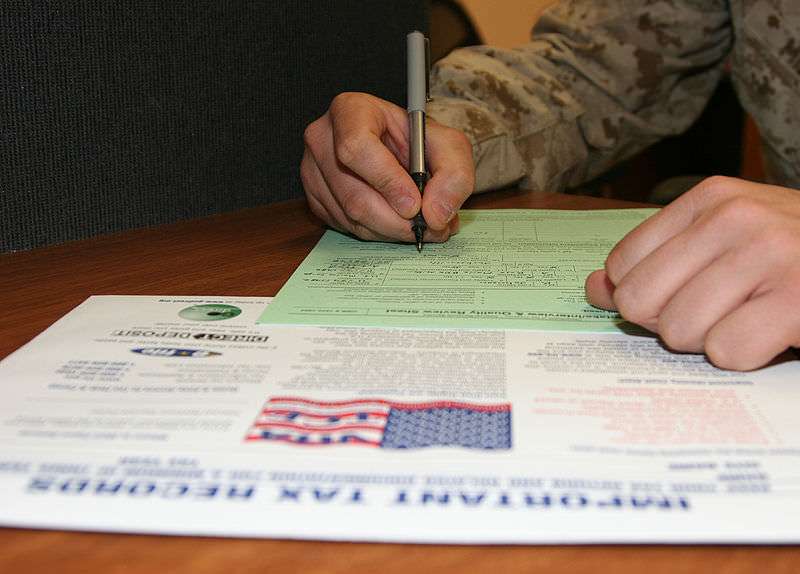

It's tax time. I'm too scared to do my own taxes. I'm sure I'll get something wrong and my enemies in government will persecute—no, I mean prosecute—me. So I hired Bob.

Bob's my accountant. I like Bob, but I don't like that I have to have an accountant. I don't want to spend time keeping records and talking to Bob about boring things I don't understand, and I really don't want to pay Bob. But I have to.

What a waste. Once, I calculated what I could do with the money I give Bob. I could have a fancy dinner out 200 times. I could buy a motorcycle. I could take a cruise ship all the way from New York to Venice, Italy, and back. Better yet, I could do some good for the world. For the same money I waste on Bob, I could pay four kids' tuition at a Catholic high school.

The tax code is now complex enough that most Americans now hire Bob, or his equivalent. Instead of inventing things, doing charity work or just having fun, we waste weeks (and billions of dollars) on tax preparation. And we change our lives to suit the wishes of politicians.

"What the tax code is doing is trying to choose our values for us," complains Yaron Brook from the Ayn Rand Institute.

I think I choose my own values, but it's true that politicians use taxes to manipulate us. Million-dollar mortgage deductions steer us to buy bigger houses, and solar tax credits persuaded me to put solar panels on my roof.

Brook objects to every manipulation in the code: "It's telling us charity is good!" On my TV show, I respond: But charity is good! Brook retorts, "If you want to give to charity, great, (but) I might invest in a business that's more important."

That's possible, but since a charity will probably spend the money better than government will, isn't it good that the code encourages people to give? Steve Forbes argues that if taxes were flat and simple, Americans would give more.

"Americans don't need to be bribed to give … In the 1980s, when the top rate got cut from 70 down to 28 percent … charitable giving went up. When people have more, they give more."

While freedom lovers complain about the byzantine complexity of the tax code, the politically connected tout their special breaks. The National Association of Realtors runs TV ads showing Uncle Sam offering first-time homebuyers an $8,000 tax break, while sleazily winking at the viewer.

The tax code oddity that may have the most destructive influence on America might be the fact that if you buy private health insurance, you pay more tax than if your employer buys you a plan.

It's why we ended up with a sluggish health care market unresponsive to individual desires—leading to the insistence that we need a government-managed alternative like Obamacare.

The code is incomprehensible. You can get a deduction for feeding feral cats but not for having a watchdog, for clarinet lessons if your orthodontist thinks it'll cure your overbite but not for piano lessons a psychotherapist prescribes for relaxation. It seems so arbitrary.

In the marketplace, individuals shop around for the most efficient, low-cost way of getting services they really want. Every time tax rules nudge us in a chosen direction, they preempt the market's signals.

Government gets moralistic about it, too, placing "sin taxes" on items like cigarettes and fat, plus luxury items like yachts that some find decadent. It's gone on for centuries. American colonists seem libertarian by today's standards, but they put extra taxes on snuff and "conspicuous displays of clothing."

That's one thing the Founders did that we shouldn't copy—but their otherwise rebellious attitude toward taxation is one that we should emulate. America suffers when government turns taxes into a manipulative maze.

Show Comments (35)