How Government Officials Doom Gun Registration Laws

The problem for gun control advocates is that they keep promising that no way will registration lead to confiscation of firearms, even as it does just that.

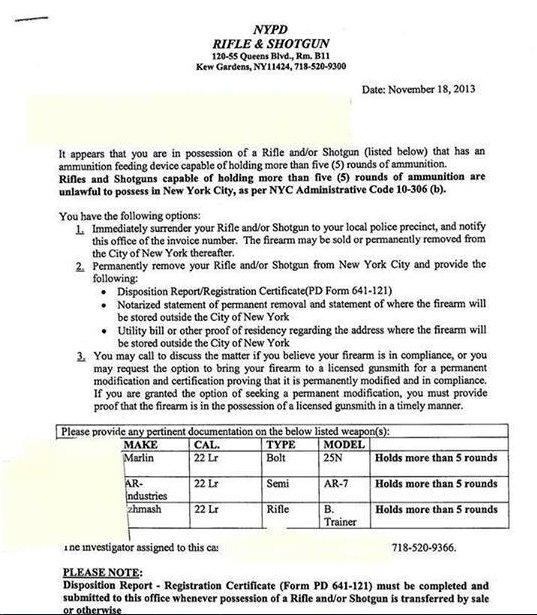

In November 2013, Robert Farago of the Truth About Guns blog began publishing letters received by gun owners in New York City demanding the surrender of rifles and shotguns that hold more than five rounds. While New York state recently passed the controversial SAFE Act imposing registration and restrictions on "assault weapons" and "high-capacity" magazines, the city law has been on the books for years, though apparently only intermittently enforced. Amidst the post-Newtown debate over gun control, though, Big Apple officials' new dedication to poring over registration records and weeding out forbidden weapons couldn't help but fuel fears of confiscation—and thereby spur defiance of already faltering registration schemes in New York, Connecticut, and elsewhere.

The problem for gun control advocates is that they keep promising that no way will registration lead to confiscation of firearms, even as it does just that. The Brady Campaign's Dennis A. Henigan accuses the National Rifle Association of peddling "fear" for even raising the possibility. In the New York Times, Charles Blow calls such concerns "cultural paranoia."

Yet gun owners seem to have legitimate worries. Hundreds of New York City residents are receiving, and publicizing, letters demanding the surrender, not of scary "assault weapons," whatever arbitrary definition may locally apply to that slippery term, but of target rifles and cowboy guns. Among the forbidden items gleaned from New York City registration lists and ordered to be surrendered or removed from city limits are the bolt-action Marlin 25N, and lever-action Browning 92 and Winchester 94 rifles. Semi-automatic rifles of the plinking variety, such as the AR-7, have been targeted, too.

Altogether, the news of the confiscation letters comes at an inconvenient time for politicians trying to convince gun owners in New York and Connecticut to register much more controversial "assault weapons"—and to take their word that nobody will try to grab the guns after they've been recorded.

California, too, has used its gun registration records to seize firearms. Under the Armed Prohibited Persons System, teams of state agents confiscate thousands of guns from Californians who have been disqualified after the fact from ownership because of "maybe a felony conviction, mental health commitment, they received a restraining order, domestic violence restraining order — some type of a misdemeanor conviction that prohibits them from possessing firearms," according to Special Agent Kisu Yo of the California Department of Justice.

A fair number of the people receiving visits from Yo and company might well be less than ideal gun owners. But those categories for disqualification are broad enough to lead many people to wonder if they might wander into them with little effort. "Some type of a misdemeanor conviction" is not hard to come by in modern America. Civil rights attorney C.D. Michel cautions, "For example, you can get in a fight, and plead guilty to being in a fight, and wind up having a statutory prohibition on possessing firearms get triggered for a 10-year period. But the courts haven't told them that."

Why take the risk of a nastygram in the mail, or armed goons at the door when you can avoid that fate by keeping your guns off government lists?

That may well be the thinking of those Connecticut gun owners who've been staying away from the state's registration forms—due by January 1, 2014—in droves. Estimates of affected weapons in Connecticut are hard to come by, though Scott Wilson, president of the pro-gun Connecticut Citizens Defense League, puts the number at 20,000 such weapons. That seems low, though, compared to the one million "assault weapons" that Governor Andrew Cuomo estimated to be affected by a similar law in neighboring (and admittedly much larger) New York, or even the 100,000-300,000 such guns targeted by a (widely ignored) New Jersey ban in 1991.

Whatever the number, though, only about about 4,100 registration applications were received by mid-November, creeping up to 6,315 in early December (along with 4,643 high-capacity magazines), with just weeks until the deadline. That led Michael Lawlor, Conecticut Governor Dannel P. Malloy's criminal justice advisor, to plaintively warn, "If you haven't declared it or registered it and you get caught … you'll be a felon. People who disregard the law are, among other things, jeopardizing their right to own firearms. If you're not a law-abiding citizen, you're not a law-abiding citizen."

Then again, history has shown that people who abide by such laws are "jeopardizing their right to own firearms."

In neighboring New York, it's hard to know how many of Gov. Cuomo's forbidden million have been registered, because the state refuses to release the number. In a state where vows of defiance of the new law have been loud and well-organized, and many county sheriffs have refused to help with enforcement, officials rely on a peculiar interpretation of a privacy provision intended to shield individual gun owners' information to keep statistics to themselves.

Robert Freeman, executive director of the state's Committee on Open Government, and the official responsible for overseeing transparency, told the Democrat & Chronicle, "If we're talking about statistics only, not the actual records that were assembled or collected, in my opinion they're public. I don't know why they would be reluctant."

Assemblyman Bill Nojay (R-Pittsford) thinks he knows why. He says the Cuomo administration doesn't want to release the data because it would show little compliance with the new gun registration requirements.

That's almost certainly true. The record shows that gun restrictions of all sorts breed defiance everywhere they're introduced. About 25 percent of Illinois handgun owners actually complied when that state's registration law was introduced in the 1970s, according to Don B. Kates, a criminologist and civil liberties attorney, writing in the December 1977 issue of Inquiry. Then, when California began registering "assault weapons" in 1990, The New York Times reported after the registration period came to a close that "only about 7,000 weapons of an estimated 300,000 in private hands in the state have been registered."

Compliance figures are unlikely to drift upwards very far, when government officials promise that no harm will come to the law-abiding—and then use registration lists to snatch cowboy guns, or to send goon squads to the doors of people caught up in bar scuffles.

Bureaucrats can nag people all they want that "If you're not a law-abiding citizen, you're not a law-abiding citizen." But policymakers have done their best to demonstrate that being a law-abiding citizen isn't always a good idea.

Show Comments (81)