How to Track COVID-19 Without Mass Surveillance

Apple and Google's Bluetooth-based app would reportedly be voluntary and anonymous. Privacy advocates say we should accept nothing less.

With lockdowns still in effect across the country, Americans are growing angry and restless. They want to resume their lives.

There's a system that could make that possible without increasing the spread of COVID-19. It's called "contact tracing," and it involves tracking down every in-person interaction that infected individuals have had in the preceding days, and then testing, isolating, and repeating the process. Several countries have phone applications that use Bluetooth or GPS to generate a record of whom individuals have come into contact with. In Singapore, downloading contract-tracing apps is voluntary; China and Israel use GPS to enforce mandatory quarantines and isolation.

In the U.S., Apple and Google have partnered to create a contact-tracking app for iPhones and Android devices.

But these technologies are raising serious privacy concerns.

"It's important that these systems are lawful and voluntary," says Alan Butler, a lawyer with the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), which has been urging Congress to build privacy protections into any contact tracing system deployed in the United States. "It's important that these systems minimize to the greatest extent possible the collection of personal information."

As in other countries, Butler says, these apps would be used in conjunction with manual data collection done via interviews with public health officials. And he cautions against systems deploying any apps that use GPS to track phones, like those being used in China and Israel. This, he says, "really changes the fundamental dynamic of…the relationship between the government and the citizen."

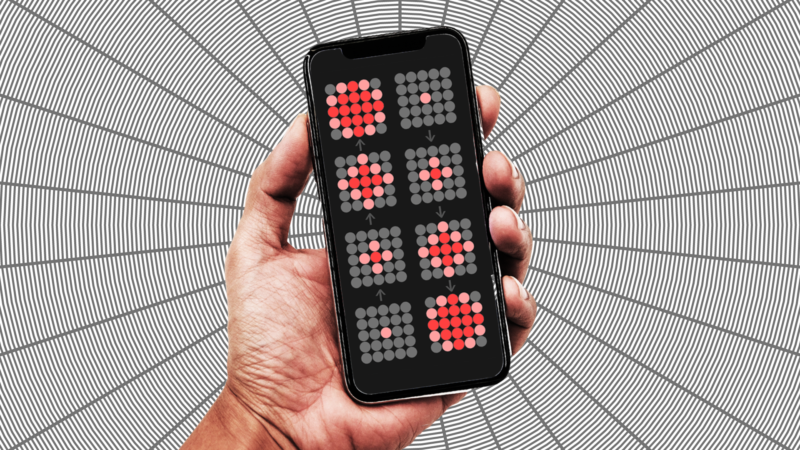

Butler says that a better approach is to use a phone's Bluetooth signal to enable virtual "handshakes" that exchange only randomized numerical identifiers, as opposed to more revealing personal information.

Attorney Peter van Valkenburgh is the director of research at Coin Center, a nonprofit advocacy group for cryptocurrency and decentralized computing technologies.

He praises aspects of Singapore's Bluetooth-based TraceTogether app, which alerts users when they've been in proximity to someone who recently tested positive for COVID-19 without revealing that person's identity.

But he objects to Singapore's decision to store phone numbers in a central database.

"We're not talking about a system that's truly privacy-preserving, because there's still this very valuable list of phone numbers that have been near other phone numbers," says Valkenburgh. "You could mine that data, and if you were sort of malicious and dedicated, you could come up with just about as accurate a portrait of a person's movement throughout their day" as you would with GPS.

Van Valkenburgh says that cryptocurrency developers, with their expertise in building privacy-preserving systems, could solve that problem. He cites a recent paper from the ZCash Foundation, where van Valkenburgh is a board member, that describes an anonymous and decentralized system for tracking COVID-19 test results. A record of Bluetooth handshakes would never leave a user's phone until that user reported a positive result.

"The data is not shared at all unless and in the event that you are sick," says van Valkenburgh. "And so that's how we keep it private and local."

He says another application of this technology could be in issuing "proof of immunity" certificates for individuals who have developed antibodies that protect them from COVID-19.

In this scenario, health officials would grant digital "tokens" of immunity to qualified individuals, who would then be allowed to engage in otherwise restricted activities such as going to restaurants, driving taxis, and walking around without a mask.

"The normal way of doing digital identity is to just have a big list of information about people," says van Valkenburgh, who uses Facebook's feed as an example. "The decentralized ledger would not include any personal identifiable information. It would just be these pseudonyms."

But truly private and decentralized systems are harder to build, and it's not clear that what van Valkenburgh envisions could be ready in the near term. Perhaps the system being developed by Apple and Google will have to be good enough.

The companies didn't respond to our interview requests. But according to the initial proposal, the system relies on Bluetooth handshakes, not GPS, to preserve location privacy. The phone identifiers recycle daily and never leave the device, unless the user reports a positive case. And the whole system is completely voluntary, with "users decid[ing] whether to contribute to contact tracing."

Apple and Google's software would maintain a central record with identifying information from the phones of those who test positive, but it would stop there, keeping those who were merely exposed anonymous.

Yet even allowing devices to identify each other through Bluetooth is a step toward weaker security that the companies wouldn't consider in the past.

"When we give up a little bit of privacy in favor of security or to address a crisis, we rarely gain that privacy back," says van Valkenburgh. "Maybe if it turns out that we can't build a solution that minimizes those privacy risks, we just shouldn't have this. We should just say, look, there are other ways to fight a pandemic."

The Apple-Google project is set for release in mid-May.

Produced by Zach Weissmueller. Graphics by Isaac Reese. Opening and closing graphic by Lex Villena.

Music by Kai Engel licensed under a Creative Commons NonCommercial License.

Photo credits: "Closed Barbershop," Marcelo Wheelock/EFE/Newscom; "Google and Apple Collaborate," Andre. M. Chang/ZUMA Press/Newscom; "Immunity Passport QR Code," Wan Quanchao/Xinua News Agency/Newscom