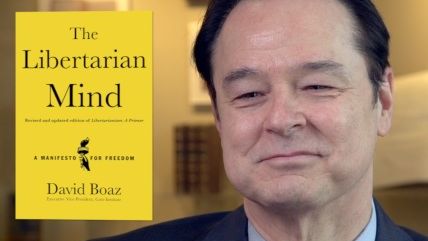

Cato's David Boaz Talks Politics, History, and His Path to Libertarianism

"I think the general idea of 'it's your life you get to run it the way you want to' is an appealing aspect of libertarianism," says David Boaz executive vice president of the Cato Institute. Over the years, Boaz has been on the libertarian forefront fighting for drug decriminalization, educational choice, private property rights, and shrinking the growth of government.

Boaz recently sat down with Reason TV's Nick Gillespie to discuss his new book, The Libertarian Mind: A Manifesto For Freedom. This is a revised and updated edition of Boaz's highly acclaimed classic book, Libertarianism: A Primer which brought the historical and philosophical roots of libertarianism to life in a compelling and fascinating read. Boaz has updated the new book with current information on the threat of government survelliance, the 2008 recession, and the welfare state.

About 1 hour.

Edited by Amanda Winkler. Camera by Joshua Swain and Todd Krainin.

Scroll down for downloadable versions and subscribe to Reason TV's YouTube channel to get automatic notifications when new material goes live.

This is a rush transcript. Please verify quotes against video for accuracy.

Reason: Hi I'm Nick Gillespie with Reason TV, and today we're talking with the Executive Vice President of the Cato Institute, David Boaz, a longtime libertarian activist and premier thinker. David, thanks for talking to us.

David Boaz: Thank you.

Reason: The exact event that we're dealing with here is "The Libertarian Mind," it's a revised and updated edition of "Libertarianism: A Primer", a book I reviewed for reason in '97, and I'm happy to say I gave it a rave review. It's subtitled now "A Manifesto for Freedom," so let's talk about "The Libertarian Mind." Talk a bit about how you define libertarianism in the book.

Boaz: In the very first line of the new book, I say libertarianism is the philosophy of freedom, so that's the easiest thing. The sentence that I developed when I was talking about this book on the radio many years ago is that libertarianism is the idea that adult individuals have the right and responsibility to make the important decisions about their own lives. Then I go onto say in the book, "Well, what does this mean?" It means economic freedom and civil liberties and I think a non-interventionist foreign policy, it means the protection of individual rights through limited government.

Reason: And the idea of limiting the government is to give more space to individuals to experiment or innovate or come up with the way they want to live their lives, and you stress this throughout, calling on thinkers from the past, as long as they're not infringing on the equal rights of others.

Boaz: Right.

Reason: One shorthand that gets used a lot for libertarianism, and I think it comes up in various iterations in your book is also that libertarians tend to be socially liberal and fiscally conservative. What is the truth in that and what's the limitation of that popular saying?

Boaz: I say that a lot when i'm talking to journalists or when I'm talking politics--

Reason: --so this is when you're talking to very stupid people, okay. Journalists and politicians.

Boaz: As you know David Kirby and I did several studies on the "libertarian vote." And obviously there we're not talking about people who read Reason magazine every month or have read my book, we're talking about, we think, tens of millions of people who are basically socially liberal and fiscally conservative. I think what's important about that politically is that it sets them apart from the red base of the Republican party and the blue base of the Democratic party and therefore if people know I'm fiscally conservative and socially liberal, or some of my colleagues prefer to say socially tolerant, then you should know that you're not a fully comfortable Republican or Democrat, and that means you should be open to thinking of yourself as independent, or maybe even grasping that you're kind of libertarian.

Reason: And this is also a way of stressing that libertarianism is kind of a pre-political designation, don't you think? I mean there's a Libertarian Party, which is important and we can talk about that, but the small "L" libertarian, it can inform your vote, but also it exists before a partisan tag.

Boaz: Oh yeah, I think that's absolutely right. Libertarianism is a philosophy, it's an attitude or a sense of life that I can make better decisions about myself then other people can. It may be a more developed political philosophy, even to the extent everything the government does seems to screw up so why don't we have less government? Or it can be a more fully developed political philosophy. But in any of those cases it doesn't necessarily tell you to get involved in politics or how to get involved with politics.

Reason: You stress that libertarianism is a political philosophy, it is, quote, "not a complete guide to life." Talk a little about that.

Boaz: Libertarianism is about the relationship of the individual and the state. It says what rights we have with respect to each other, and it says what rights we have with respect to the government, and what powers the government should have. But beyond that, as the famous communitarian philosopher said, "the language of rights is morally incomplete." Yeah, no kidding!

It's actually a very minimal set of rules: Don't hit other people and don't take their stuff. Then we build a legal system around those very simple rules. But it doesn't tell you how to treat your spouse, or how to treat your friends, or how to treat your employees. I know there are businessmen who say, "I apply libertarianism insights in my business," and they may, and those may work for them, but there's nothing in libertarianism mandates about how you treat people other than not hitting them and taking their stuff.

Reason: But could a libertarian really be unlibertarian on a personal or private level? If you're really a libertarian in your politics do you have you to be a libertarian in your personal life?

Boaz: Well I've known enough libertarians to know they don't have to treat other people nicely. So I don't think it's very likely. You know, it's like, you have to pretty a doctrinaire libertarian if you just don't like gay people, but you still support gay rights. Similarly, if you are a real misanthrope, and you want to treat people badly, and particularly treat them as if they were not autonomous individuals. Now as a legal matter you have to, but yes you could say, I'm going to pay good wages but I'm not going to give you a moment's peace if you work for me, that doesn't seem like a likely things a libertarian would do. But yeah as a libertarian I would say, if you want to make that offer to people and people accept bad working conditions, they have a right to do it.

Reason: You identify with a natural rights tradition, as opposed to consequentialism or utilitarianism or various other justifications. Talk a little about the natural right tradition and how that influences your libertarianism.

Boaz: Natural rights to me means I hold this truth to be self-evident: that everybody has the right to live his life the way he chooses, so long as it doesn't violate the natural rights of others. And I think that tradition can be traced back to Aristotle, Aquinas, Locke, Mill, Herbert Spencer, and into the 20th century. Even the Austrian economists, thought they're generally regarded as consequentialists, I think you see the notions of treating people as rights-bearing individuals. And then in a more modern era of Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard. But I want people to understand this is not something invented in the late 20th century by Rand and Rothbard. It has a long history, but it is the idea that we have rights as individuals, and if we set up government, it's to protect those individuals' rights.

Reason: And the government, going back to the Declaration of Independence, that a government that does not respect those rights actually deserves to be overthrown.

Boaz: We have a right to alter or abolish it.

Reason: But you talked about how many of the these we consider the libertarian core of belief, especially in rights to act the way that you want, actually stem from a religious base that arose in the religious civil war in 17th century England. Talk a little bit about the levelers and about the English civil war and about how even though today libertarianism is widely considered a haven for atheists, much of what we consider libertarian thought really started in a religious-based civil war.

Boaz: In going back even before that, I think you can say that a lot of the fundamental ideas of libertarianism developed through the Judeo-Christian theory of the autonomous individual, the thinking individual, the natural law, the individual who gets to read the bible and has a personal relationship with Jesus.

Reason: We all have a soul, so we are God's property in some sense and not each other's.

Boaz: That's right, you can trace that back to give unto God what is God's and unto Caesar what is Caesar's. It establishes that there are things that are not Caesar's. That establishes that the government doesn't own your whole life, it doesn't own the whole world. But then you get to the English Civil War. Yes, a lot of ferment in the 17th century, dissatisfaction with the Stuart kings, who were perceived as coming in and trying to change the traditional English constitution which respected the rights of Englishmen, and arrogate more power into the monarchy. You have robust debates going on, and you have a group of people called the Levelers. Like most political names, this was given to them by their opponents. All they wanted to do was level rights, they believed in equal freedom under the law, they didn't believe in leveling society [in terms of outcomes or money]. There was in fact another group of people who called themselves "true levelers" and they really were like socialists. Other people called the the "true levelers" the diggers, because they dug up the land of the aristocrats. But the Levelers were putting together a program based on their Christian faith originally. It was based on the autonomy of every individual and the responsibility that every individual has to God, not to the king. The king is only there for so long as he respects our rights. So they talked about individualism, individual rights, religious freedom, because there were arguments going on there between the Catholic church, King Henry's Episcopal church, and people who actually wanted real protestantism.

Reason: And freedom of conscience, a freedom to worship God as you saw fit.

Boaz: That's right. And so those kinds of things merged with their political theory, their defense of property rights, their defense of manhood suffrage, to create what we could consider the first recognizably libertarian political platform.

Reason: And of course, [this line of thinking] harkens back to even a pre-Christian era with tragedies such as Sophocles' Antigone, which is all about a person that refuses to follow the mandates of the political leader because she is answering to a higher law.

Boaz: That's right.

Reason: What is the evidence of the fact that we're in kind of a libertarian moment or a libertarian era?

Boaz: We've tried to announce the libertarian moment several times, but we might be in better shape here. One of the things certainly, is in my view, that creates libertarian moments is government overreach. People will see government is getting too big and it isn't working very well. So you had the financial crisis. There's a big argument over what caused that. Was it rapacious, unfettered capitalism on Wall Street? Or was it shaped by bad decisions by the Federal Reserve causing the mistakes in the market. And to the extent that a significant number of people accepted that latter point, it's the Federal Reserve and overregulation that caused it.

Reason: You were saying the overreach--I mean whatever caused it—people were bothered by the corrections government pushed: OK, we're bailing out auto manufacturers! That was never popular. Bailing out banks was never popular.

Boaz: Yes that's right, in September of 2008, you have this crash start to happen, and you have the government respond really in a completely undeliberative, unelected way. My memory of that fall is every Monday morning the head of the Fed, the secretary of the treasury and the head of the New York Fed would announce what they did over the weekend to destroy the remains of the free-enterprise system. And small government people felt like we were being slapped in the face every Monday morning with these announcements. It was a very depressing time to be a libertarian or a small government person. And obviously a president promising a big expanded view of government was about to get elected, and then announce a health-care takeover and the hugest spending bill in the history of the world. But, the other thing that starts going on during this period was a pushback. Sales of Atlas Shrugged start soaring, sales of The Road to Serfdom start soaring, sales of the Cato institute's pocket Constitution made The New York Times' best seller list in October 2008. So there's that pushback, and then the rise of the Tea Party. The Tea Party is not a libertarian movement exactly, but was a libertarian force in American politics. It was against big government, big spending, big debt, health-care takeover.

Simultaneously, on Election Day 2008, gay marriage is defeated in California. Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton, all the Republicans are against it, and it looks like wow, it just took a big hit. And then, over the coming year, judges and legislators in more states started endorsing gay marriage. And then, over four years it gets so big, that Barack Obama has a long dark night of the soul and changes his mind. And now he's in favor of it. Simultaneously you have a marijuana legalization movement that's been around for many years. I had a New York Times op-ed in 1988 on why we should end the drug war. But suddenly around 2008-2010, it starts actually winning a couple of elections. So all of those things I think are part of the libertarian moment. Then, as you folks at Reason have stressed, much more than I do, the cultural aspect of the libertarian moment. New technologies that are allowing people to make their own music, publish their own books, publish their own magazines, find their own cab drivers, all sorts of things, that feel more libertarian, and give more people the sense that they can make decisions in the marketplace that they weren't making before.

Reason: Does the sense that people are rejecting party labels such as Democratic or Republican add to the sense that something is happening. People are less interested in being an old-style Republican or Democrat or even a liberal or conservative.

Boaz: There are a lot of political scientists who say there aren't really independents. If you push voters, they admit, "Yeah, I always vote Republican" and that sort of thing. But still, the number of people that say they're independents is growing, and that certainly shows an increasing dissatisfaction with both parties, in particular the Democratic Party, which has always had a plurality of the electorate. They're losing that now to independents. And [work I've done with David Kirby and others] shows that a large percentage of those independents are libertarian in the sense that they are, shall we say, socially liberal and fiscally conservative. Some of them, and this is the reason why you can't organize the independents, some of them are independent and swing voters because they're socially conservative and fiscally liberal. They're basically the anti-libertarian on a range of things. On the other hand, they're very anti-establishment. They don't like the big boys in Washington, so I think a candidate, maybe it's Ronald Reagan, maybe it's Rand Paul, a candidate who can appeal to that anti-Washington ethos might pick up some of those people, even though ideologically they shouldn't.

Reason: Talk about a recent governor's race in Virginia, where the democratic candidate was Terry McAuliffe, who's very closely tied with the Clintons, is kind of a standard Democrat liberal. Ken Cuccinelli, Virginia's attorney general, was a very standard-issue Republican, pretty socially conservative but also very small government, at least in many of his proclamations. And then there was the Libertarian candidate, Robert Sarvis, who got what, 8 or 9 percent of the vote?

Boaz: I think he only got 7 percent, but he'd shown 10 or 12 percent in the polls.

Reason: He more than covered the gap between them, although, exit polls showed that he pulled more from McAuliffe than from Cuccinelli, which is fascinating. Is this a test case where if either Cuccinelli or McAuliffe could have appealed to swing voters, Cuccinelli might have triumphed, or the margin of victory of McAulifee would have been much bigger?

Boaz: Well sure, if either one of them could have picked up a substantial number of Sarvis's 7percent, he would have won a comfortable victory. I think what you had there was a really right-wing Republican, and a really corrupt hustler liberal Democrat. And so it was kind of a tailor made for a third party to kind of get some attention. And I know the Libertarian Party was thinking, wow, if we actually had some money, or if the media covered us, think of what we could have gotten in a race with those two very flawed candidates. But yeah, I think Sarvis showed that there is this group of people that will even vote for a Libertarian if they hear his name, and you kind of had an essence of Republican and essence of Democrat candidate, and a lot of people didn't like them.

Reason: There seems to be a part of the Libertarian moment or an ascendancy, I think in the first time in my life, people are seriously talking about libertarian wing to the Republican Party. Where did that come from, and is that for real?

Boaz: Well, I said to Rand Paul the other day, I keep reading these headlines about the libertarian wing of the Republican party, and I'm like, who is this wing? It's Rand Paul!

Reason: Yeah, and maybe a couple of others.

Boaz: There's a couple of others, and I do think that the Tea Party and Rand Paul together have made people think, "Oh, there's some kind of libertarian wing." The election of Justin Amash, and Thomas Massie, and the election of Mike Lee and Ted Cruz are perceived as being different from establishment conservatives, even though it's not clear that they're libertarians, but they're very strongly free market, and ticked off about the way the government is trying to run the economy. So there's that kind of libertarian wing, but it's also true, if you look at votes, take the Amash amendment, to restrain the NSA, it split both parties, got about 40 percent of both parties on its initial vote on the Hill.

So that suggests that there was a libertarian wing of the Republican Party, maybe even a libertarian wing of the Democratic Party. What we haven't been talking about here is foreign policy. I think 13 years of war has caused even a lot of Republicans to say, "When is this ever gonna end? Why are we doing this?" And they're now saying, a majority, I think, of Republicans, this war was a mistake. So Rand Paul has been the person leading that effort, but neocons are complaining about an isolationist wing of the Republican party. I mocked them in 2012 and said, the neocons said there's an isolationist wing in the 2012 debate? Excuse me, from the former US trade representative Jon Huntsman, from the businessman Mitt Romney, who are these people who are isolationist? These are people that are saying, you know, maybe we're in enough wars and it's time to wind them down. So that's a change in thinking.

Reason: Where's the libertarian appeal the strongest? Foreign policy is one of these areas where majorities of people, now anyway, are saying that the invasion of Iraq was a mistake. That Afghanistan, it's not clear what it achieved, and we're still there, we have 15,000 troops. Talk about why people are rethinking foreign policy. Is there something beyond just fatigue or failure?

Boaz: Well, there are two fundamental things that go on in American understanding of foreign policy, I think. One is generally a lack of interest in running the rest of the world. We have these two big oceans, we don't have to get involved all over the world, and a lot of Americans are perfectly happy not to. We don't speak very many foreign languages, and that kind of plays into, "We don't need to do that." But there's also this Scotch-Irish attitude, that if anyone kicks us, we're gonna kick back. So when you see beheadings, or the attacks on 9/11, or anything like that, you get a very strong push among the American public to hit back. Now the libertarian argument is if you weren't over there in Iraq then ISIS, wouldn't be beheading Americans. So, stay out of conflicts and you won't have to get into further conflicts.

Reason: Do you buy that?

Boaz: Yes.

Reason: In a broad sense, but then in a local sense it's not clear, is it? If you're beheading freelance journalists covering the Syrian civil war…

Boaz: Yes, that's right, but most of what goes on in the Middle East, in the first place, there wouldn't be a broken Iraq if there was no Iraq war and there might not be a Syrian civil war. And maybe it's a good thing that people want to get rid of Assad, but it wouldn't be drawing us in. So no, I don't think it would be the same thing. If we didn't already have war there, there wouldn't be the same desire to go in and fight there with respect to libertarianism, but it does come up against this: we hit back when someone hits us.

Reason: Part of the pushback [against non-interventionism] is that there is also a military-industrial complex, which Eisenhower famously named and warned against. People all over Washington and in the country get a lot of defense dollars. They don't really care about being overseas, they just care about the $500 or $600 billion a year in the baseline defense budget. They want to make sure it oesn't get cut, and in fact grows.

Boaz: Well, if all that the defense budget cost us was the $500 or $600 billion, that would be better than going to war and costing us lives and entanglement. I think actually foreign policy is an area where the libertarian argument has more resonance with the people than it does with the elites, but because people tend not to vote on foreign policy issues, that means the elites get to run things. So you've got a liberal internationalist establishment in the Democratic party and a neocon establishment in the Republican party, and those two together, though they would have trouble winning an election, or a referendum in the whole country, nevertheless control Washington.

Reason: Yet libertarians don't shrink from an integrated world.

Boaz: No, I think the whole term isolationism--there are a few Americans who are isolationists, traditionally, some people didn't like international trade, they didn't want to learn languages or go overseas, and they didn't want our troops overseas. So that's isolationism. And Pat Buchanan might be an example of that today. But libertarians are very much cosmopolitan, we want to trade, we want cultural interaction, we want to get books and ideas and people. We're open to liberal immigration rules. The one thing we want to minimize is political and military intervention in the rest of the world. So that's simply not isolationism, it's non-interventionism.

Reason: And non-military interventionism. Where are other places where you think the libertarian appeal is at its strongest?

Boaz: I think clearly one of the strongest appeals is, Don't raise taxes. In fact, cut taxes. It's disappointing to me that the taxpayer movement has never been more successful than it has been. Because it is very hard to win against an argument that we should do more for education, more for healthcare, do more for transportation. Where you can win is by explaining, "It's gonna cost money." So we shouldn't tax more and we shouldn't go into more debt. Those two things, no debt and low taxes, I think are very strongly resonant with the public.

Reason: One of the problems though, is that if you keep cutting taxes but you don't cut spending, you get into a very bad situation. It seems that politicians have learned that you can actually cut taxes and keep spending more and more. I mean, this is the lesson of the George Bush presidency.

Boaz: Or the lesson of the Reagan presidency.

Reason: Actually the lesson of all presidencies since Eisenhower.

Boaz: Well that's right, and I think among libertarian scholars there's a lot of argument over this "should you starve the beast" or does cutting taxes without cutting spending lead you to say, "Hey, spending is free!"

Reason: Paul Krugman, for instance, says, that with interest rates so low, we should be taken on as much debt as we can, because it's never going to be this cheap again.

Boaz: That, again, I think is an elite argument that appeals to Democratic spenders but does not have much resonance with the American public. I think that no debt and low taxes have stronger popular appeal. And we argue about what is the practical impact. I still pretty much come down on Milton Friedman's side, that you want to cut taxes and cut spending whenever you get the opportunity. But I appreciate that [Nobel laureate economist] James Buchanan and [former Cato chairman] Bill Niskanen were very smart advocates of limited government—

Reason: —and they had the argument that, when you raise taxes, spending will actually go down because they suddenly realize what they're paying for.

Boaz: Well, there were arguments about that, and my sense is that Bill Niskanen sort of changed his mind on that. He did not believe that this idea of a grand bargain, raise taxes and cut spending, was going to work, although he had at an earlier point.

Reason: Foreign policy, taxes, what else is another big appeal for libertarianism right now?

Boaz: I think the idea of "it's your life, run it the way you want to," is an appealing aspect of libertarianism. Unfortunately in political terms, many voters are susceptible to saying that in principle, but then upon being told that what some other person wants to do is smoke marijuana or engage in a homosexual relationships or worship the wrong god, in different periods of American history, people have reacted against that. And liberals, modern American-style liberals, not us classical liberals, will tend to say sure people should be able to make their own decisions, but not if that means not contributing to the public good by paying 50 percent in taxes.

Reason: Or not selling cakes to gay people, or not selling cakes to homophobes. Or if you start saying the wrong thing. So where do you think the libertarian appeal is the weakest? Where are places that large numbers of people still need convincing that libertarianism is a smart way to think about the world.

Boaz: Well, you're talking about Americans, right? Because in a whole lot of the world the idea of religious freedom is still a problem. In America, I think the drug war is still something that even though we're starting to win a couple votes on marijuana, we're a long way from persuading people that other drugs should be legal. And that's an issue libertarians have talked a lot about, probably is associated with libertarians in the minds of reasonably informed people, so that's been a challenge for us, and it's one we have talked about.

Reason: What about immigration? And I know there's a smattering of libertarians who are anti-immigration for various reasons, but overwhelmingly libertarians believe in the flow of goods and services across borders, and we believe in the free movement of people. That seems to be a radically unpopular in contemporary America.

Boaz: I don't think it's radically unpopular, I think if you look at the polls, most people are reasonably sympathetic to a moderately liberal immigration policy. They believe that immigration is good for America, they believe that we should be open to immigration, they believe we should control our borders and control the flow, but they're generally pro-immigration. However, there are a significant number of people who we would generally regard as being pro-free market and anti-big government, anti-federal government, who are vociferously anti-immigration. So yes, in terms of putting together a political majority, there's a lot of people who don't like immigration.

Reason: What do you think drives the anti-immigrant sentiment, particularly among conservative Republicans? They seem to be the most vocal.

Boaz: Well to some extent the conservative reaction is simply against change. People don't like change. My Scotch-Irish ancestors came to this country before the Declaration of Independence, and I'm sure along the way they didn't like the Germans, and they didn't like the Irish, and they didn't like the Jews and Italians, and now they don't like the Hispanics. There's a zero sum economics attitude, that they will come in and take our jobs, which is is just a misunderstanding of the way the economy works. There is clearly some element of opposition to difference, racial difference.

Reason: It's a form of tribalism.

Boaz: Tribalism, yes, there is that. And there is also going along with it, a somewhat legitimate attitude about rule of law. These people are here illegally while my ancestors or my cousins waited in line. Now I always say to the anti-immigration people like Pat Buchanan, you know when your ancestors came in the 19th century, my ancestors were sitting here waiting for them and they grumbled about it, but there were no restrictions. You were allowed to come in. So when you say your ancestors were legal, they were only legal because there were no barriers. So what would your ancestors do if Ireland were suffering a potato famine, and America had restrictions on immigration? They might just come in anyway. But it's a legitimate concern that things should happen according to the law.

Reason: There always seems to be an unwillingness to say, you know, if we change the laws [to let more people emigrate legally], more people will migrate legally.

Boaz: It does not seem to lead them to say, Why don't we change the law?

I want to finish answering your question about what's most difficult. Because one of the very difficult things for us to sell to a whole lot of people is the idea that specific things the government will do to you is a bad idea. That the government, in fact, doesn't run good schools, it doesn't run good healthcare, its not even the best way to build roads and bridges, and all of these things together will be built inefficiently, and they will cost a lot of money. The stuff you think is free will end up costing you more than you would have paid for it in the marketplace. So just the general idea of the government as Santa Claus is a real obstacle to a libertarian or any other small government, fiscally conservative politics.

Reason: I think libertarians flatter themselves to say, Well the difference is that we think systematically and other people just aren't that evolved. I know tons of people who are smart, have tons of degrees, and might say, I don't think the government should be doing that but I get a National Science Foundation grant, and the government should definitely be funding that. Is one of the ways the we persuade more people to the efficacy or the effectiveness or the goodness of libertarianism is by trying to create more systematic thinkers?

Boaz: Yes, it's probably good if more people are systematic thinkers. On the other hand, there are plenty of PhDs--Paul Krugman won a Nobel Prize in economics--yet he doesn't agree with us on very much. So we can't just say, if people were smarter and could think better… It's still probably good for the world if people can think more logically, but it's not an automatic ticket to winning. One of the things you point out, though, is that each new government program creates a new constituency. So, the National Science Foundation, childcare subsidies, or the highway for your district. All of those things create people who were not previously advocate of big government, but now are required to rally around and defend the farm subsidies or whatever. So one of the reasons that we so very much want to stop these new programs is that each new one creates a new constituency.

Reason: Which then, in order to get its concentrated benefit, is willing to add pennies to its tax bills to pay for everybody else.

Boaz: Yes.

Reason: Talk about global warming and environmentalism. I think this is a case where there are very strong libertarian arguments about the way forward. But it often comes up as one of the places where libertarianism has no way of solving or even acknowledging that collective action is needed to stop the planet from boiling in its own juices. What is the libertarian response to that?

Boaz: I think it's a difficult issue, I don't think that you solve that problem by saying, "I have no systematic theory or rules on what I think the government should do, anything that looks good to me I'm for." What is your political philosophy that defines what's appropriate for the government and what's not? Is it you think that everything is the purview of the government.

But for libertarians, it's an issue. As far as global warming goes, my own view, base on Pat Michaels' work at Cato--we're the only think tank with an actual climatologist on the staff--is that the globe is warming, it's partly man made, it's not going to be catastrophic. The globe has warmed and cooled over the millennia, and there's no evidence that it's gonna be particularly dangerous. However, that doesn't mean in theory that it couldn't be. A hole in the ozone layer, or something else like that, could be devastating, and then you have public-action problems. And yes, I think libertarians should think more carefully about what we would do if that were the case. And I don't know if I have a good answer other than decentralization, trying to avoid command and control solutions. A strict respect for property rights typically gets you better answers and better internalization of costs.

Reason: You're implying as well that, South Florida, which has had [extreme] weather for a long time, and Holland, they do a pretty good job of coping with environmental variance and catastrophe, in a way that Bangladesh doesn't.

Boaz: Well, that's right. The most important thing in solving these problems, like the spread of ebola in Africa, or the threat of exaggerated hurricanes here, is wealth. Create more wealth. Our buildings are much less likely to fall down because we're a wealthy country and we value having buildings that don't fall down. In Bangladesh they may value them, but they don't have the money. In Africa, in the countries affected by ebola, they just have not created enough prosperity to be able to afford the medical infrastructure that would make ebola easily manageable. So, the answer to healthcare problems in Africa, to many of the world's environmental problems, is to have a more prosperous world, to create more wealth, which can then be spent on the real challenges.

Reason: What are the best ways to boost economic growth?

Boaz: We may be, because of demographic reasons or whatever, in a period where growth can't be as high as it could have been. On the other hand, it was running at 3 percent before [the financial crisis]. China's been running at 9 percent but they had a lot of catching up to do. I'm betting we could do better than 3 percent if we had lower taxes, less regulation on the economy, less cronyism and protection for established business. Take Uber as an example: Here we have this 50-year-old taxi cartel in every city and every state, and a new business comes along and wants to break up this cartel and provide more service, better competition, and the cartel fights back. So breaking up cartels from the taxis to the banks to whatever is one way to do it to open up the economy and get more entrepreneurship, get more things happening, but the burdens of taxation and regulation make that difficult.

Reason: How do you prevent upstart businesses from suing for peace and creating a new cartel once they've established themselves? That's already happening with Uber, which is now playing with certain cities' commissions to keep out other services. Is that just part of the free market, that big government and big business work hand-in-glove?

Boaz: It's not part of the free market, it's part of the politicized market.

Reason: Let me put it this way, it's an excrescence of the free market, because once you have a wealthy business, you can start spending more money on things, one of the things you start spending it on political favors.

Boaz: Yes, but if we had a more strictly applied constitution or had written the Constitution more strictly in the first place and the government wasn't allowed to create monopolies, for instance, then it wouldn't do you any good to pay politicians to create a monopoly. So in a free market, protected by law that actually guarantees a free market, then this would be less of a problem. In our current politicized market, then it is. I just read the Virginia legislature on a bipartisan basis is sitting down with Uber and Lyft to discuss rules to enable them to operate. The first rule is they have to pay $100,000 for a license. Well, Uber can afford that, but there might be a lot of potential businesses who can't afford $100,000. So yes that absolutely looks like the established players, now including Uber and Lyft, will be able to get some barriers to entry created by the legislature.

Reason: What are the challenges to the libertarian paradigm? Last year saw the publication in English of Thomas Piketty's book, Capital, where's he's basically saying that we are now entering a new Gilded Age. It's worse than that, even, in his telling. The have get all the returns and the have-nots are locked out. Returns to individual laborers can't catch up to the returns on capital. Do you see that as a fundamental challenge, or a credible challenge to the free market perspective?

Boaz: I suppose that it's a credible challenge. I'm not an economist and I certainly am no expert on what's good or bad in Piketty's work. Piketty made an argument that was attractive to the world's leading media, and so it was immediately hailed as the most important book of the decade and so on. And there were no critics, because who's read it? It's 800 pages and it's a brand new book. And so the media report, "He shows this" and then after the month-long media hype, economists start actually plowing their way through it, and my understanding is that they have uncovered significant questions about the theory of the increasing returns to capital, serious questions about the actual data in the book, and so on.

So five years from now, how influential will Piketty's book be? I don't know, but it made a big difference there. But yes, inequality and the perception of inequality is a big issue. One thing I think libertarians say—which possibly isn't always compelling to people—is, "Would you rather be equal at low incomes or unequal at higher incomes?" Every day that Microsoft stock goes up, the gap between me and Bill Gates gets greater. I have a little Microsoft stock, so I make $10 that day, he makes $100 million that day, but I don't see that as bad for me. So in general it seems to me that the problem we ought to be concerned about is poverty and the stagnation of middle class wages. So rather than focusing on, "We don't want Bill Gates to be rich or get richer," we should focus on, "What are we doing wrong that might improve the problem of poverty or middle class incomes.

Reason: Is that really where the battle is being drawn? Inequality does seem to be growing. The gap between the richest Americans and the poorest Americans is growing and middle class incomes seem to be stagnating. But even Obama isn't talking about, "You know what, I'm going to go after those malefactors of wealth, the billionaires." He ends up attacking people who are in the top 10 percent or the top 20 percent. So it's not that Bill Gates gets rich, but that somebody is making twice or three times as much as me. We've got the same education, we started out in the same place--that seems to be where the rub comes, isn't it?

Boaz: I'm not sure about that, it seems to me that what we hear about is billionaires, and billionaires are in a completely different place. Yes, there has been some stretching out of middle-class incomes. Charles Murray talks about how [in the past], if you were good at math you could be an engineer and make twice as much as the factory worker. But now if you're good at math you can become a Wall Street quant and make 100 times what the factory worker does. That may seem unfair, but the market is about satisfying human needs, and if it turns out that your skills, once not very useful, are now incredibly useful to make our economy work better and to provide more real wealth for people, then that's a good thing. I saw a chart of incomes from 1979 [to the current time] for the various income classes the other day. What it shows is the bottom four quintiles are all up roughly forty percent in that period. The top 20 percent is up twice that much and the top 1 percent up a thousand percent. Okay, that is rising inequality, but it's also significant increases in living standards for all Americans, and that seems to be better than what would be the results of seriously trying to restrain inequality.

Reason: But this is Obama talking to Joe the Plumber, saying, "Why don't we take just some of that wealth at the top and spread it around a little, that's fair."

Boaz: That's right, and it's easy to say that's fair, and if you take a little bit extra from the billionaires, really, are they gonna stop working? But as you say, it's not just the billionaires that will be hit by these taxes, it's the people who are currently working and building businesses. Because you can't get that much from billionaires, and if you try to take a lot of what they have then yes, they will stop creating companies and they will stop working. It's a bad thing for America and for the world that Bill Gates stopped working because he had enough money and went into philanthropy. He was brilliant at creating new connections and new wealth for society, it's too bad that he's not doing that any more.

Reason: I suspect many Microsoft employees would agree with you, that he should have kept working. Here's a possible challenge to the libertarian paradigm: millennials. And I know that you've done some work on millenials, Reason has done an in-depth poll. Millennials, on a certain level, are very libertarian. They hate things like nanny state rules, they hate soda bans, they hate smoking bans. They want more choices in their lives, they don't have the same kind of sexual or racial hangups that older Americans have. They're very cosmopolitan, they're very loose, they're very free in that way. But a majority of them believe that the government should guarantee you healthcare, should guarantee you a job, should guarantee you lots of stuff. Is that mentality a standing challenge to a libertarian paradigm?

Boaz: Oh, I think it is. You know, my friends who run Students For Liberty, and Emily Ekins who does this polling work ,keep trying to convince me that millennials are essentially libertarian. "This is the most libertarian generation ever!" I look at those polls and I see that millennials have an incredible faith in a government that I think they know has been a huge disappointment in a whole range of areas. And yet, they want this magical government to provide jobs, provide housing and so on.

Now, one answer to that may be that when they get in the workforce and start paying taxes they'll have a different view on how much the government should do. On the other hand, millennials are either in the work force and paying taxes or not able to get jobs because of economic policies. So we may be [entering] a period of trying to argue to this generation, "What is it that isn't working? Is it the rapacious untrammeled capitalism that isn't working, or is it the burden of taxes and regulations?" I think it is the burdens we're placing on the market causing so many young millennials to not be able to find jobs, to still be in their pajamas at their parents' house, talking about a need for health care.

Reason: One of the things that's interesting is that libertarian thought, and the political philosophy that it comes out of is the belief that you and I and everybody is an autonomous individual, who should be given wide latitude to make choices in their life, choices of who to vote for, of what to buy, what to wear, how to organize their lives--

Boaz: --how to worship.

Reason: There's a lot of pushback now from evolutionary psychology and even economics that says, Wait hold on. Individuals are actually much more subject to forces that direct and control them that we didn't really pay attention to. And so you have people like Cass Sunstein talking about nudging people, or creating a framework which will direct people to the "right" decision. You have people that say that advertising--the hidden persuaders—are increasingly effective at goading people to buying certain things. Even Nobel prize-winning economists like Vernon Smith, a phenomenal libertarian and a really interesting economist, who says that his experimental economics really consistently shows that he can take freshmen and teach them a couple of rules in an investment system, and within the second or third trial we'll be doing exactly what the system tells them to do. Somebody like Charles Murray says, "Look, some people just don't have the wherewithal to really make the best choices for their lives." Is the libertarian paradigm at risk from an attack from people who say, "You know what, this idea that we're making meaningful choices is just a bunch of hooey."

Boaz: Well, we may all be living in the Matrix, but the thing about the Matrix is you don't know that. So I am certainly not conversant enough with all of these schools of thought to have a rational opinion about it. I guess what I would say is society works best if we let people make decisions, whatever way we're making them. We will get better results if we act as if people have free will, if they have autonomy, if we hold them responsible for the consequences of their actions. Even if there may be some unfairness because they had something in their brains causing to them to do this. And we should continue to study these things, and maybe we'll find out something better, but I think we've learned from trying socialism and central planning and theocracy, and various kinds of ways of actually regulating through force what choices people can make, that you get worse results. Do you get ideal results, or perfect results from people making their own decisions? Maybe not but I think you get better results than any other social-political system will give you.

Reason: This is an interesting point that you raise. Libertarianism is often accused of being utopian, but it really is profoundly anti-utopian, because it's never talking about the one best way or the final breakthrough. It's about the process that allows people to discover to discover what they want and what they should be.

Boaz: Right, it's a discovery procedure, it's a framework for utopias. You can try to set up the way you'd like to live and I can try to set up the way I'd like to live. And some of those ways will turn out to be more attractive to people than others. You know this idea that advertisers or anybody else can shape what we think, yeah up to some extent, but it's also true that sometimes their big budget movies fall flat on their faces, and there's the old story about, you know, we've tried everything with our advertising and we still can't people to buy the dog food, why is that? And finally the intern says, "Dogs don't like it."

Reason: Talk a little about what are the challenges to kind of a libertarian political movement or social movement that you find particularly challenging.

Boaz: There are a lot of challenges to our political movement. Right now there aren't enough of us and we don't have enough money. To the extent that we do have money, it tends to go all into economic issues, regulation and taxes, and not into broader parts of libertarianism. That may itself connect to one of the challenge we face, which is that a lot of us grew up in a world where it seemed like everyone in America was white except the 10 percent were black, and they didn't have a whole lot of involvement in shaping politics or public life.

Reason: And they were men as well.

Boaz: That's right. And now we're in a much more diverse world. Libertarianism has the image sometimes of being a white guy's club and so we need to work on diversifying, to have more women, more people of color involved. We see that among younger groups, you definitely see a more diverse group in Students for Liberty than you do at an older donor's conference. You see a much more diverse group among Cato's interns than among Cato's middle-age policy staff, so I think that is partly changing, but I think it's also that we need to think more about talking about issues of race and class, and talking about ways that appeal beyond our logical Austrian-Randian-INTJ white guy syndrome.

Reason: You talk about this in the book, both in terms of feminism and gender equity, as well as racial equity. What is the libertarian line on these things?

Boaz: Well, the history is very good. Libertarians are the heirs of classical liberalism, and who was it who first said after thousands of years, challenge slavery? Some Christians, but mostly Christians [with] liberal values. Who first said women are equal to men? Classical liberals, proto-libertarians. And the same thing with gay rights. The only people who challenge the general societal attitude toward homosexuality were classical liberals.

Reason: You point out that the Libertarian Party in 1972, as part of its platform, had gay rights, and at that point, homosexuality was still considered a mental illness [by most psychiatrists].

Boaz: Yes, and a crime in many states. So yes, libertarians have been ahead of the game up through slavery, Jim Crow, gay rights--

Reason: And you point out as well there's kind of a founding matriarchy of the post-war libertarian movement in terms of Ayn Rand, Isabelle Patterson, Rose Wilder Lane. But this is kind of like Rand Paul going to Howard University and stopping his history of how great the Republican Party was on race in the 1920s. What is the contemporary pitch to women and minorities? The pitch that says: Actually, libertarian thought is the place that you should be looking at.

Boaz: I think that, to women the pitch is, absolutely we believe every individual, every adult individual is equal, everybody should have the opportunity to fulfill their dream, to pursue their dream as they choose, which might be being a homemaker, and it might be being a CEO and everybody gets to make that choice. And to the extent that there are some feminists that want the government to care of women, whether traditionally by barring them from certain occupations or these days by mandating them in certain occupations, by guaranteeing childcare and birth control or whatever, well libertarians have to disagree with that. But individualism and equal dignity, we're there on that. With Hispanics, we obviously talk a lot about liberal immigration rules, we also talk about this country being a land of opportunity, and let's make it store so, and let's have better schools, and those are the things that help people rise. With the African-American community, I think we did sort of for a generation drop out of that battle, and libertarians need to get back in it. And what can we say to people in the African-American community? The Cato Institute runs policemisconduct.net. We're the people monitoring police misconduct around the country. We are the people criticizing the drug war, which brings such a heavy military presence and criminal presence, prison presence, into black communities. We're talking about giving poor people more options in schooling, and that would be so much of a benefit to poor people, which disproportionately includes African-Americans.

Reason: Let's talk a little bit about your personal odyssey to libertarianism. You hail from Western Kentucky, you're Scotch-Irish, so that means that family gatherings must be quite a combustible affairs, and particularly if Kentucky bourbon is involved. What's your intellectual genealogy? How did you start to become a libertarian, when did you start calling yourself that?

Boaz: My parents were both well-educated and conservative. I grew up sort of a Jeffersonian constitutional conservative. In my part of the country we were still all Democrats back then, but Democrats who voted Republican a lot of the time. And so I got interested in these ideas, and thought of myself as a conservative, I guess I wasn't a very rebellious kid at that time, so my parents were conservative and that's what I read. I read Henry Hazlitt, and that was pretty much all the economics I was going to learn. You read Economics in One Lesson, and that's the lesson. I read Barry Goldwater's Conscience of a Conservative, which is a very libertarian book despite its title, and that gave me a framework for understanding public policy, and then actually I read a couple of issues of--

Reason: Can I ask you before we move off of Coldwater, how did you square his Conscience of a Conservative with his later book, Why Not Victory?, which was a brief for military victory in Vietnam and elsewhere. It was a kind of massive anti-Communism, which makes a hell of a lot of sense, but there's a militaristic component to that which Goldwater embraced but not fully (I think he was always against the draft). Were you more of a conventional conservative, who believed "we've got to go over there, we've got to be on the Korean peninsula, we've got to be in indochina, we've got to be everywhere where the bugs might show up and get them before they take over land"?

Boaz: At that time I was a pretty conventional conservative. As you know it was pretty common for conservatives who thought that the federal government couldn't do anything competently except maybe deliver the mail nevertheless thought it could have this massive military establishment throwing its weight around the world, confronting Communism all over. When I was 14 years old, my first published article was a call for victory in Vietnam, so yes, I bought all of it.

Reason: The South Vietnamese, right?

Boaz: Yes!

Reason: So you encountered Goldwater, you've read Henry Hazlitt, and then what starts happening that you pull into a libertarian--

Boaz: Well, I became a subscriber to New Guard, the magazine of Young Americans for Freedom--

Reason: Young Americans for Freedom was the conservative student group that was founded by Bill Buckley.

Boaz: Yes, and around 1970 I read a few issues, and they were really focusing on the conflict between freedom and order. They had radical libertarian writers and radically traditionalist writers, and I began to see libertarianism is the emphasis on freedom, and so that pushed me in a libertarian direction, and then I read Ayn Rand, and that pretty well pushed me into the libertarian camp. But I still thought libertarians were sort of a kind of conservative, and so I got involved in Young Americans for Freedom. I became the editor of New Guard magazine.

Reason: When you were editor, what were the issues that were really hot in the moment?

Boaz: Well I was editor in the late 1970s, so the first and second Reagan presidential campaigns were certainly shaping things there. And opposing Jimmy Carter and his energy policy. As a young conservative-libertarian activist in Washington, I worked with Jimmy Carter on resisting the draft until he switched sides, and on the deregulation of transportation. So I was able to say, "This guy's good on this, but all this overweening energy regulation we're against," and, you know, in a partisan Republican kind of way as well, we're just against Jimmy Carter. And I went to the Republican convention in 1976 as a Reagan advocate. Four years later I opposed Ronald Reagan because I was supporting the Libertarian Party candidate, so somewhere in there I had made a transition.

Reason: Was there some kind of Damascus Road experience where you realized libertarians are not a version or a type of conservative, but a whole different species?

Boaz: Well, I did some more reading, I read Rand, I read some [Murray] Rothbard, I ran into [Cato Institute founder] Ed Crane and [author and activist] Tom Palmer through the Libertarian Party, and got beaten on by them, to understand the contradictions within conservatism, and began to feel more and more uncomfortable. YAF was always undergoing internal fights, and I kind of ended up on the wrong side of a factional fight, and fortunately had become libertarian enough to get a job in the libertarian movement. So right there around 1979 I got my first job in the libertarian movement, and then I jumped ship to go work for the Ed Clark campaign. I really learned [a lot during the] Ed Clark campaign, really learned how to write libertarian articles on behalf of Ed Clark.

Reason: Ed Clark was in the 1980 presidential election, and he scored, what, a million votes? Or 900,000—

Boaz: 900,000 votes and 1.1 percent of the popular vote.

Reason: It was the best showing a Libertarian candidate had until Gary Johnson did basically the same numbers [in 2012]. A little bit higher in terms of total votes, a little bit lower in percentage.

Boaz: That's right.

Reason: What was appealing to a million people, basically, or 1 percent of the voters in an election in 1980. There was Jimmy Carter, there was Ronald Reagan, there was John Anderson. What was it about Ed Clark that managed to pull one percent?

Boaz: Well, one percent is not much.

Reason: But relatively speaking, it's pretty good.

Boaz: Yeah, well, relatively speaking. I do think Clark came across as a serious, thoughtful guy, and he had a semi-professional campaign, which is probably better than the Libertarian Party has done in recent years. But you have to say that one of the significant things that he had was money from David Koch, who was his running mate, which was the only way a then multi-millionaire, later billionaire, could actually give a lot of money to a presidential campaign. So Ed Clark was able to run, as I recall, 47 five-minute advertisements on primetime network television back when there were only three networks. And that has to be the explanation, but the message was the American tradition, individual liberty, individual rights, here is what the Republicans are doing wrong, and what the Democrats are doing wrong. He could have gotten more votes if Ronald Reagan hadn't been a pretty libertarian rhetorician that year, and I think he would have gotten more votes if John Anderson hadn't been there, because Anderson was sort of a liberal Republican. He wasn't one of those Moral Majority types, and so I think he took a lot of the attention the third party candidate could have gotten, and he took some of the votes of the socially liberal, fiscally conservative group.

Reason: And the Clark-Koch campaign, they were running on things such as the abolition of the FBI and the CIA, right?

Boaz: I don't remember specifically, did we say that? We might have—

Reason: I think so—

Boaz: We certainly…we had a list of a whole bunch of government programs we were gonna abolish--

Reason: I mean it was a wonderfully hardcore libertarian recission of government roles and responsibilities. This was coming out of a decade where every day you would wake up to a new exposé of how awful the government had been. And not just simply misdelivering the mail, but surveilling people—

Boaz: COINTELPRO and Watergate and Vietnam.

Reason: Let's talk about intellectual property, which is a hot issue and has become more so in a kind of digital age. Libertarians love property rights. So intellectual property rights would be great, right? Ayn Rand was a big believer that if you wrote it, you owned it forever and ever and you could transfer it to an heir indefinitely. Copyright law, ironically, is starting to approximate that, because every time Mickey Mouse or some other big company's property is about to go into the public domain, the copyright term gets extended.

Boaz: I am a very strong property rights advocate, so my instinctive position is what I call "Ultramontane Randianism." If you build a house, you may bequeath that house to your son and his son and his son and his son. If you right Atlas Shrugged, why is that not just as much a product of your effort as a house? And so why can you not bequeath the rights of that novel to your son and his son and his son, or your intellectual heir, or whatever? I've had lots of conversations with people who have thought about this and the implications of that. We realized that there were some differences here among libertarians, so we had a Cato staff lunch where we were gonna come present these things, and it turned out to be… You think Scotch-Irish family gatherings are a problem? This turned out to be people throwing food at each other over whether it is a right or merely a consequentialist argument, or merely something established in the Constitution as a positive right in order to advance the useful arts and sciences.

Reason: I mean, it's a government granted right to monopoly in the Constitution for a limited period of time--

Boaz: Well, it's a government granted right if you look at it that way. If you look at it the Randian way, I created this. If you created the movie Star Wars, why should Reason TV be able to do parodies or simply sell the movie? And obviously there are differences there between just selling the movie, or doing a parody of it, or doing the sequel or whatever. And do you get to copyright the characters, or the concept, or whatever? I have certainly moved in the direction of, "Gee, these issues are more complicated, and we don't want to stifle creativity. Gee, would I really want Shakespeare's works to still be under copyright?" On the other hand, we'd still buy them, we'd still pay $12.95 for the book, so would it really make a difference? So I have to say that's one where I have moved from a dogmatic position to mostly confusion.

Reason: Well, that's the story of life, I hope, to move from dogmatism to confusion.

Finally, let's talk about 2016. We've just come through a midterm election that was just short of a landslide for Republicans. They now control the House and the Senate, which means that they will probably reveal themselves to be utterly contemptible over the next two years. But in 2016, we have people like Rand Paul, who's clearly running or gunning for the Republican nomination. Do you think 2016 is going to be a libertarian year, or will libertarian issues be front and center?

Boaz: I think there will be a lot of libertarian issues being talked about. I think endless war is an issue that certainly Rand Paul will talk about, and other candidates are going to respond to that. On the other hand, there may be conservative issues in the sense that, if ISIS is still marauding in Iraq and Syria, then there's gonna be a strong neocon argument that we gotta go in and fight that. But yeah, I think war will be [important]. I think NSA surveillance is still going to be an issue on the table that most of the Republicans would just as soon not deal with, and the Democrats, too. But if Rand Paul is running, which I'm pretty sure he will be, he'll be talking about it.

And then the general issues of the size of government, what should we do about inequality, what should we do about poverty. All of those have libertarian answers. Gay marriage may be off the table by then because the Supreme Court may take it off, and I don't think conservatives will respond the way they did to Roe v. Wade and go on a 40- year crusade to repeal it. This is not about the taking of life, this is about letting people get married. And I think after a year of letting people get married, Republicans will say yeah, whatever. Marijuana might be a bigger issue, probably not a presidential level issue, because I don't think anybody's going to want to take it up, but I do think Rand Paul will be running, and I think he will talk about these kinds of issues, and he will get beat up by the establishment conservative media, and all the other Republican candidates and so it will be interesting to see whether he can hold up to all of that.

Reason: Do you agree that the "the Libertarian Moment" doesn't really turn on whether Rand Paul is the Republican nominee or not.

Boaz: That's right. Historical trends are bigger than any one candidate. I think we can look and see if Ronald Reagan had not been the Republican nominee in 1980, would things have been different? Probably so. So it does make a difference, but government programs will continue to falter, the economy will continue to struggle because of the burdens placed on it. We will continue to get ourselves involved in unnecessary wars. The president talked in the State of the Union speech about being dragged into unnecessary conflicts. Of course, he's bombed seven countries and Bush only bombed four, so he should know. All of these things will continue to be problems, and if Rand Paul doesn't get elected president, people may decide, as they did with Ronald Reagan, "Boy, we made the decision last time, we should vote for him next time." Or other libertarian candidates will surely emerge.

Reason: We've been talking with David Boaz, he's the executive vice president of the Cato Institute and the author most recently of the new book "The Libertarian Mind," a revised and updated version of "Libertarianism: A Primer." It's also subtitled "A Manifesto for Freedom." David Boaz, thanks for talking.

Boaz: Thank you.

Reason: For Reason TV, I'm Nick Gillespie.