A Judicial Solution for Presidential Overreach and Congressional Abdication

The Supreme Court should take a page from its own history.

The recent high-profile cases of Trump v. Slaughter and Learning Resources v. Trump might not initially appear to share very much in common. Yes, they both involve President Donald Trump, but the former is about the president's purported authority to fire the heads of federal agencies at will, while the latter is about the president's purported authority to unilaterally impose tariffs. Totally different legal issues, right?

Well, yes and no. Trump's name may dominate the headlines, but both cases are also about the actions of Congress. Or perhaps it might be better to say that both cases are about the inactions of Congress; about how Congress has relinquished its lawmaking power over many years both to the executive branch and to the executive-ish federal agencies who wield what a notable jurist once called "quasi-legislative" authority. In other words, both cases are about the separation of powers.

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

The framers of the U.S. Constitution famously divided power among three branches of government so that, as James Madison explained in Federalist 51, the "constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places." The constitutional separation of powers was absolutely vital, Madison argued, because "ambition must be made to counteract ambition."

Notice the key assumptions on which this argument rests: Madison assumed that each branch would seek to enlarge its powers; but he also assumed that each branch would jealously guard its powers from being seized by the other branches.

President after president after president has certainly behaved as Madison assumed. But what about Congress?

Consider the constitutional authority "To declare War," which is granted exclusively to Congress via Article 1, Section 8. Yet Congress has officially done nothing in response to Trump carrying out repeated acts of war without even the slightest hint of congressional authorization. When an ambitious president meets a supine Congress, what's left of the separation of powers?

What's left is the third branch of government. Madison described the proper role of the judiciary as being "an impenetrable bulwark against every assumption of power in the legislative or executive."

I know what some of you are thinking, and you're right: The Supreme Court has undeniably failed to perform that judicial duty on many occasions. But there are some estimable past examples worth remembering, and emulating, today.

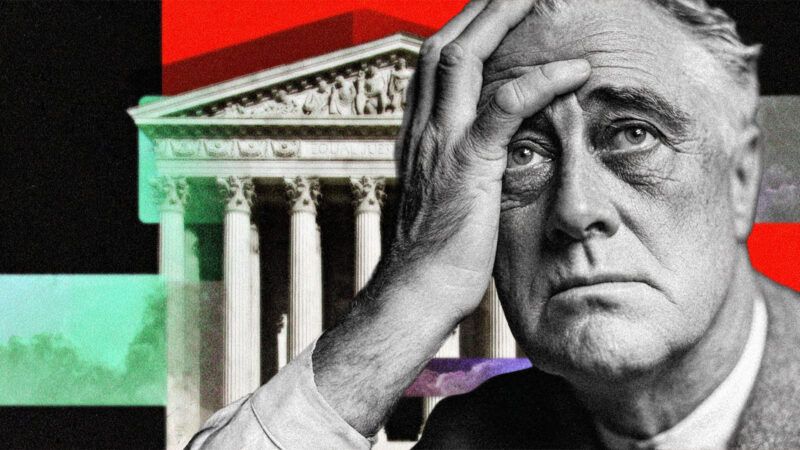

In 1935, the Supreme Court weighed the fate of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA), which President Franklin Roosevelt had championed as "the most important and far-reaching legislation ever enacted by the American Congress." Among other things, the NIRA placed unprecedented lawmaking power in the hands of the president.

Yet "such a sweeping delegation of legislative power" cannot be reconciled with the Constitution, declared Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States. "Congress cannot delegate legislative power to the President to exercise an unfettered discretion to make whatever laws he thinks may be needed or advisable for the rehabilitation and expansion of trade or industry."

The Court's Schechter ruling was 9–0, which meant that even the Progressive legal hero Justice Louis Brandeis lined up against Roosevelt. In fact, shortly after the decision came down, Brandeis personally delivered a blunt message to White House lawyers Tommy Corcoran and Ben Cohen. "This is the end of this business of centralization," Brandeis said to them, "and I want you to go back and tell the president that we're not going to let this government centralize everything."

By enforcing the non-delegation doctrine (and other venerable constitutional principles) in Schechter, the Supreme Court did its part to enforce the separation of powers. And the Court did so, it is worth noting, even though the legislative branch had voluntarily surrendered some of its powers to the president.

That same judicial solution to the intertwined problems of executive overreach and congressional abdication is still an option today. Or at least it is still an option if the current Supreme Court is prepared to do its job.