What Kristi Noem Gets Wrong About Habeas Corpus

The legal principle safeguards civil liberties, protecting even unpopular people from the government.

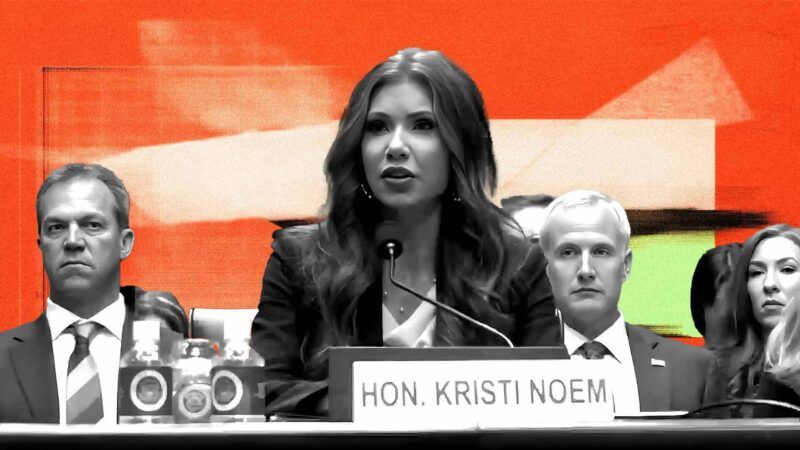

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem at a congressional hearing on Tuesday had a contentious exchange about habeas corpus, the constitutional right that allows people to challenge their imprisonment in court.

Sen. Maggie Hassan (D–N.H.): What is habeas corpus?

Noem: Well habeas corpus is a constitutional right that the president has to be able to remove people from this country—

Hassan: No, let me stop you ma'am—

Noem: —and suspend their right to, suspend their right to—

Hassan: Excuse me, that's incorrect.

Noem: President Lincoln used it.

Habeas corpus is a fundamental civil liberty: It effectively forces the state to justify why it is detaining someone. It is, by definition, a check on the government, not a right it possesses.

Noem is likely aware of this. The homeland security secretary told lawmakers at a different congressional hearing last week that immigration levels may justify suspending the protection. Giving her the benefit of the doubt, then, it's possible she meant to imply today that President Donald Trump needs to subvert that right in order to deport people. And perhaps that is also what she meant by her reference to former President Abraham Lincoln, who did not most famously "use" habeas corpus but rather suspended it during the Civil War without congressional approval—an action that was later found to be unconstitutional.

Viewing the exchange in a light most favorable to Noem, it generally comports with the administration's position. Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff for policy, said earlier this month that Trump is "actively looking at" suspending habeas corpus for migrants. "The president of the United States," Noem said later in the hearing today, "has the authority under the Constitution to decide if it should be suspended or not."

But that is highly constitutionally dubious, as Reason's Jacob Sullum wrote last week, for a few reasons. The first: The clause that allows for its suspension—"the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it"—is found in Article I of the Constitution, which governs Congress. The executive's powers are outlined in Article II.

That is in large part why Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Ex parte Merryman (1861) that Lincoln had violated the Constitution when he unilaterally suspended the right, which, in terms of the present-day debate, the Supreme Court has also confirmed applies to people in the United States unlawfully. (Congress ultimately approved Lincoln's suspension in 1863, about two years after his initial decree.)

Then there is the justification the Trump administration would have to invoke: that the U.S. is experiencing an "invasion," or that public safety is endangered so severely that it requires suspending a core constitutional protection. Whatever your views on immigration, the reference to invasion, as Sullum notes, has historically been understood (including in the courts) to reference literal warfare—a military attack, for example.

The "public safety" invocation would likewise be extremely tenuous, particularly when considering, for example, the Supreme Court's ruling in Boumediene v. Bush (2008), which affirmed that Guantanamo Bay detainees, who were also noncitizens, had the right to habeas corpus. If terrorism suspects are entitled to those petitions, then it stands to reason so should people like Rümeysa Öztürk, the Tufts student who was recently released from detention after a federal judge ruled the government had provided no evidence for her imprisonment other than that she co-authored a pro-Palestine op-ed.

Habeas corpus, and the Constitution broadly, protects unpopular people for a reason—and it protects them from the government. The president certainly has a prerogative to uphold the law. But that doesn't mean much if he and his administration engage in lawlessness to do so.