Community Fridges Are Facing Vandalism and Regulatory Challenges

The community fridge is a civic model that regulators should encourage, not seek to shut down.

Community fridges—refrigerators parked on city sidewalks by volunteers who stock them with food that hungry people may take as they need—are facing a raft of challenges from crime and vandalism. If that weren't enough, some community fridges are also facing the ax from overzealous regulators.

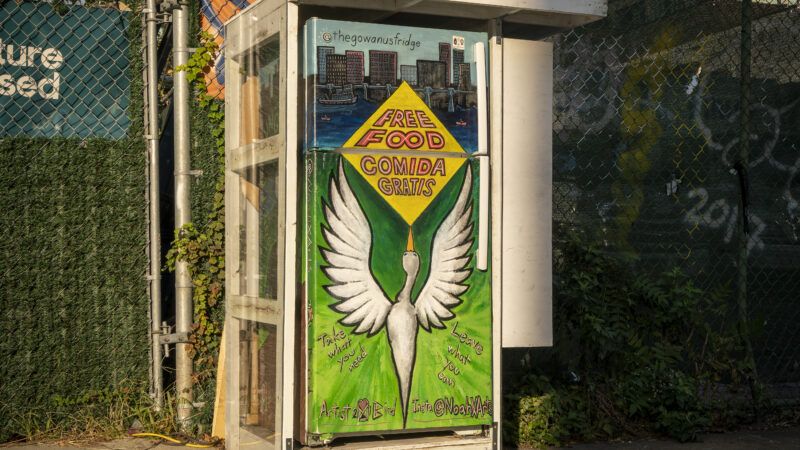

As I explained in a column last year, a "community fridge" refers to a working refrigerator that volunteers plug in on a city street and stock (and restock) with food that anyone can take and eat free of charge. Community fridges operate like microscopic, hyperlocal, decentralized food banks. They are, I opined, "exactly the sort of community-building and local self-reliance that America needs right now."

But right now, crime appears increasingly to be hampering the operation and spread of community fridges. In July, a community fridge in DeKalb County, Georgia, was vandalized and its contents strewn across the street. That particular fridge, which had been vandalized previously, is operated by a mutual-aid organization that's reduced the fridges it operates from six to two since it began operating in 2020. A month earlier, in Philadelphia, a community fridge and its contents were stolen right off the street—presumably to be sold for scrap.

But those examples of theft and vandalism pale in comparison to what's happened to a couple who regularly stock a community fridge that's located near their home in Portland, Oregon.

"Jeana and Mark Menger sleep with their car keys near their bedside, and they have a plan," The Oregonian reported in July. "Should a man who has frequented the community refrigerator full of free food on their Portland street make good on his vow to burn down their bungalow, they will climb out their bedroom window and drive off to safety." The paper notes residents who live near the community fridge also face other, perhaps lesser negative externalities, including human waste, rodents, and vandalism.

These are just some of the latest threats faced by community fridges and their supporters. Despite those threats—some literal and terrifying—the biggest challenges facing the community-fridge model across the country may still be regulations that prevent them from operating at all.

Indeed, as I noted in my column last year, community fridges in some cities and towns "are in jeopardy due to an unwelcome combination of outdated laws and overzealous regulators." In 2020, for example, code enforcement officers in Sacramento shut down a community fridge there, dismissing it as nothing more than "dangerous" "'junk' and 'debris.'" Then, earlier this year, code enforcement was at it again. They shuttered a city council candidate's community fridge with the same junk-and-debris claim. The city has since sent out warnings to others operating community fridges in the city, threatening them with hundreds of dollars in fines.

In Des Moines, Iowa, last year, the city ordered a resident farmer to close the community fridge in her yard. The city told farmer Monika Owczarski, the Des Moines Register reports, that "zoning permits the placement of sheds only in side or back yards" and "the refrigerator and the open-front shed housing it are a secondary structure on a property in a residentially zoned neighborhood without a primary structure—another violation of the city's code." The report also notes this was at least the second such time the city had ordered a community fridge to close due to misguided zoning rules.

Despite these continued challenges, many still see promise in the community fridges model. It's easy to see why. They allow people to help others in their communities directly, allow people in need to choose foods that are right for them and their families, reduce food waste, foster community, and other positive outcomes.

But overzealous regulations and regulators—along with crime and other challenges—have limited their reach and effectiveness. That problem, alas, is as old as community fridges themselves. After the first community fridges appeared in Germany about a decade ago, according to a group called Whole Healthy Group which promotes the use and spread of community fridges, "[g]overnment authorities intervened around 2016 and shut down most of the fridges[.]"

At a time of record-high food prices and crushing inflation, lawmakers should be doing more to ensure they lower or eliminate regulatory burdens to allow community fridges to be made available wherever charitable people see a need they wish to address.