After Climbing 3 Years in a Row, U.S. Pot Busts Fell by 18% Last Year

The odds of getting arrested for consuming cannabis are getting smaller.

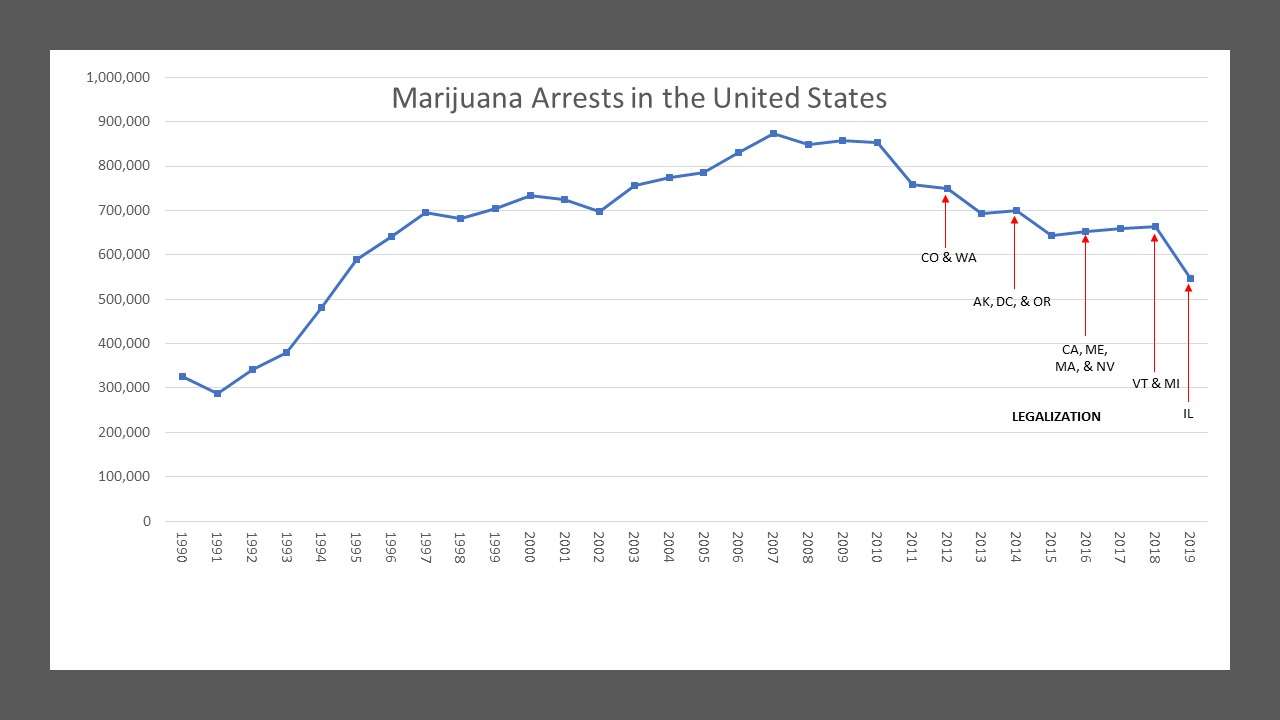

After rising for three years in a row, marijuana arrests in the United States fell by 18 percent in 2019, according to the FBI's latest numbers. Police made about 545,600 marijuana arrests last year, compared to about 663,400 in 2018. As usual, the vast majority of those arrests—92 percent—were for possession rather than manufacture or sale. The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws reports that "much of the national decline resulted from a drop-off in marijuana arrests in Texas in 2019, which experienced over 50,000 fewer marijuana-related arrests last year" than in 2018.

Nationwide, marijuana arrests peaked at nearly 873,000 in 2007; last year's number was 37 percent lower. While the odds that any given cannabis consumer will be arrested have always been low, they are getting lower. Possession arrests in 2007 represented about 3 percent of marijuana users that year, judging from survey data. That risk last year, when there were more marijuana users and fewer arrests, was down to about 1 percent.

As the above graph above indicates, marijuana arrests are down 27 percent since Colorado and Washington became the first states to legalize the drug for recreational use in 2012, but the decline has not been smooth. After dropping in 2013, pot busts rose in 2014, fell in 2015, then rose slightly for three consecutive years before dropping substantially in 2019. During that period, nine other states and the District of Columbia legalized recreational marijuana, although Vermont and D.C. do not allow commercial distribution.

Since possession had been legalized in eight states—including California, the most populous—by 2017, it may seem surprising that marijuana arrests continued to rise until last year. But in California, possession of an ounce or less for personal use had been treated as a citable offense punishable only by a $100 fine since 2011. So while California accounts for 12 percent of the U.S. population, it accounted for less than 2 percent of marijuana arrests in 2016.

Four of the other jurisdictions that legalized marijuana in 2012, 2014, or 2016—D.C., Maine, Massachusetts, and Oregon—likewise had already decriminalized possession of small amounts. In Alaska, Nevada, and Washington, possession was still a misdemeanor, while Colorado treated it as a "petty offense." Another thing to keep in mind: Public marijuana use remains an arrestable offense even in states that have legalized possession, cultivation, and distribution. Still, the increases in marijuana arrests after these jurisdictions legalized recreational use suggest that other states picked up the slack.

Three more states—Illinois, Michigan, and Vermont—legalized recreational use in 2018 or 2019. Illinois and Vermont had already decriminalized possession, as had many cities in Michigan. In 2016, Michigan's share of marijuana arrests was about the same as its share of the national population. As you would expect, Vermont, which has a tiny population (about 0.2 percent of the national total), accounted for an even tinier share of marijuana arrests (about 0.02 percent). But Illinois accounted for about 12 percent of marijuana arrests that year—three times its share of the U.S. population.

In 2014, Washington Post reporter Aaron Blake found that Illinois had more marijuana arrests per capita than any other state. The rate in Illinois was 80 percent higher than the rate in New York, which was the runner-up even though it supposedly had decriminalized possession of up to 25 grams (nearly an ounce) in 1977. New York's law still allowed arrests for possessing marijuana that was "burning or open to public view," a loophole that the New York Police Department used to launch a cannabis crackdown during Michael Bloomberg's administration, when low-level pot busts in the city skyrocketed. The state legislature closed that loophole last year.

As New York's experience shows, "decriminalization" is not necessarily as meaningful as it sounds. Even after Illinois decriminalized possession of less than 10 grams (about a third of an ounce) in 2016, people caught with more than that amount could still be arrested. Yet decriminalization, perhaps combined with a reassessment of police priorities, seems to have had a dramatic impact in Illinois. According to the Chicago Sun-Times, police in that city made 129 arrests and wrote 300 tickets for marijuana possession in 2017, compared to 21,000 arrests in 2011. Legalization had an additional effect: The Associated Press reports that marijuana arrests in the Chicago area plummeted after legalization last year.

While the risk of arrest is small and getting smaller, it is not evenly distributed across the population. This year the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reported that blacks are 3.6 times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession as whites, even though rates of cannabis consumption in the two groups are similar. That was about the same as the ratio that the ACLU reported in 2013.

Racial disparities persist even after decriminalization and legalization. In 2017, the Sun-Times reports, four-fifths of the people busted for marijuana possession in Chicago were African Americans, who account for about a third of the city's population. After states legalize marijuana, the ACLU found, the black-white gap shrinks but does not disappear. In Colorado, for example, public use remains illegal, and blacks are almost twice as likely to be arrested for such offenses as whites.

As with New York City's anti-cannabis crusade, which overwhelmingly targeted blacks and Hispanics, there are possible explanations for these disparities that do not involve racist intent. If police concentrate their resources in high-crime neighborhoods or if people with smaller living spaces are more likely to use marijuana outside, for instance, those factors would be apt to increase the risk of legal trouble for black cannabis consumers. But the fact remains that skin color predicts how likely a pot smoker is to be arrested, which is a troubling state of affairs, regardless of intent, for a country that aspires to equal treatment under the law.

While people arrested for marijuana possession generally do not spend much time behind bars, they suffer long-lasting ancillary penalties. A marijuana arrest or conviction makes it harder to get an education, make a living, and find housing. That's why clearing the records of marijuana users (and growers and sellers) who were unlucky enough to be caught is an important, although frequently overlooked, part of reversing, or at least ameliorating, the injustice inflicted by pot prohibition.