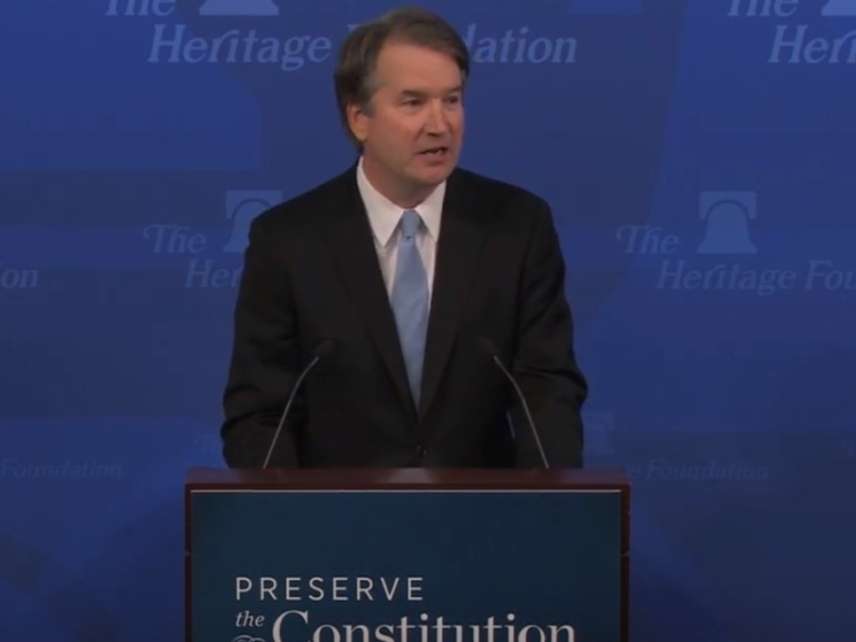

SCOTUS Contender Brett Kavanaugh on Gun Rights, Search and Seizure, and Mens Rea

The D.C. Circuit judge is a strong defender of the Second Amendment but seems less inclined to accept Fourth Amendment claims.

Last week I suggested that whoever replaces Anthony Kennedy on the Supreme Court probably will be more receptive to cases that challenge gun control laws on Second Amendment grounds. That certainly seems to be true of Brett Kavanaugh, who by some accounts is the leading contender for Donald Trump's second Supreme Court nomination, which the president plans to announce on Monday night.

Kavanaugh, who has served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit since 2006, dissented from a 2011 decision in which a three-judge panel upheld the District of Columbia's ban on so-called assault weapons and its requirement that all guns be registered. Kavanaugh disagreed with the majority's use of "intermediate scrutiny," saying an analysis "based on text, history, and tradition" is more consistent with the Supreme Court's Second Amendment precedents.

The D.C. "assault weapon" ban covers a list of specific models as well as guns that meet certain criteria. A semi-automatic rifle that accepts a detachable magazine is illegal, for instance, if it has any of six prohibited features, including an adjustable stock, a pistol grip, or a flash suppressor. "The list appears to be haphazard," Kavanaugh noted. "It bans certain semi-automatic rifles but not others—with no particular explanation or rationale for why some made the list and some did not." In any case, he concluded, the law is inconsistent with the landmark 2008 case District of Columbia v. Heller.

"In Heller," Kavanaugh noted, "the Supreme Court held that handguns—the vast majority of which today are semi-automatic—are constitutionally protected because they have not traditionally been banned and are in common use by law-abiding citizens. There is no meaningful or persuasive constitutional distinction between semi-automatic handguns and semi-automatic rifles. Semi-automatic rifles, like semi-automatic handguns, have not traditionally been banned and are in common use by law-abiding citizens for self-defense in the home, hunting, and other lawful uses. Moreover, semi-automatic handguns are used in connection with violent crimes far more than semi-automatic rifles are. It follows from Heller's protection of semi-automatic handguns that semi-automatic rifles are also constitutionally protected and that D.C.'s ban on them is unconstitutional."

Although Heller suggested that various "longstanding" gun restrictions would pass constitutional muster, Kavanaugh said, D.C.'s gun registration system does not qualify. "Because the vast majority of states have not traditionally required and even now do not require registration of lawfully possessed guns," he wrote, "D.C.'s registration law—which is the strictest in the Nation and mandates registration of all guns—does not satisfy the history- and tradition-based test set forth in Heller."

Kavanaugh also is sensitive to the constitutional implications of regulations that interfere with freedom of speech. In 2009, a year before the Supreme Court overturned statutory restrictions on the political speech of unions and corporations in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, he wrote an opinion rejecting FEC rules that made it harder for advocacy groups to raise money.

The FEC regulations, which were challenged by the abortion-rights group Emily's List, required nonprofit organizations to pay for election-related activities largely with "hard money" subject to donation limits. "Because donations to those hard-money accounts are capped at $5000 annually for individual contributors," Kavanaugh noted, "the FEC's allocation regulations substantially restrict the ability of non-profits to spend money for election-related activities such as advertisements, get-out-the-vote efforts, and voter registration drives." That burden, he concluded, cannot be reconciled with the First Amendment, which "protects the right of individual citizens to spend unlimited amounts to express their views about policy issues and candidates for public office" as well as "the right of citizens to band together and pool their resources as an unincorporated group or non-profit organization in order to express their views."

Kavanaugh seems to take a narrower view of Fourth Amendment rights. In 2010 he dissented from the D.C. Circuit's decision not to rehear a case in which a three-judge panel had ruled that police violated a suspected drug dealer's Fourth Amendment rights when they tracked his movements for a month by attaching a GPS device to his car without a warrant. Kavanaugh rejected the idea that the tracking constituted a search because of the quality and quantity of information it collected, although he anticipated the argument that ultimately persuaded a majority of the Supreme Court: that the physical intrusion required to plant the tracking device amounted to a search.

That rationale would not support invoking the Fourth Amendment in cases where information is collected without trespassing on someone's physical property, as when police use cellphone location records to figure out where a suspect was at particular times on particular dates. Last month the Supreme Court ruled that looking at such data is a search, meaning it generally requires a warrant.

Kavanaugh also dissented in a 2008 case involving a man named Paul Askew, who was stopped by D.C. police because his clothing was similar to an armed robber's. The cops patted Askew down for weapons, as permitted under the 1968 Supreme Court ruling in Terry v. Ohio, but found nothing. Later they unzipped his coat, supposedly to facilitate an eyewitness identification, and found a gun.

The D.C. Circuit concluded that police went too far when they unzipped Askew's coat and that the gun, which became the basis for a weapons charge, should not have been admitted as evidence against him because it was the product of an illegal search. Kavanaugh disagreed, saying unzipping the coat could be justified as "an objectively reasonable protective step to ensure officer safety" after Askew "actively resisted" the pat-down or because "police may reasonably maneuver a suspect's outer clothing—such as unzipping a suspect's outer jacket—when, as here, doing so could help facilitate a witness's identification at a show-up during a Terry stop."

While Kavanaugh typically has not sided with criminal defendants, whether they were seeking to overturn their convictions or shorten their sentences, there are some notable exceptions. In 2012, for instance, he wrote the majority opinion that overturned a military commission's conviction of Salim Hamdan, who admitted serving as Osama bin Laden's driver, for providing material support to terrorism:

When Hamdan committed the conduct in question…the international law of war did not proscribe material support for terrorism as a war crime. Indeed, the Executive Branch acknowledges that the international law of war did not—and still does not—identify material support for terrorism as a war crime. Therefore, the relevant statute at the time of Hamdan's conduct—10 U.S.C. § 821—did not proscribe material support for terrorism as a war crime.

Because we read the Military Commissions Act not to retroactively punish new crimes, and because material support for terrorism was not a pre-existing war crime under 10 U.S.C. § 821, Hamdan's conviction for material support for terrorism cannot stand.

In another 2012 case involving an unsympathetic defendant, Kavanaugh dissented from a decision upholding an armed robber's conviction for carrying a machine gun in the course of a violent crime. Kavanaugh argued that the offense—which triggers a mandatory minimum sentence of 30 years, compared to 10 years for a violent criminal who carries a semi-automatic firearm—requires knowledge that the gun is capable of automatic fire.

"The majority opinion holds that a person who committed a robbery while carrying an automatic gun—but who genuinely thought the gun was semi-automatic—is still subject to the 30-year mandatory minimum sentence," he wrote. "The majority opinion thus gives an extra 20 years of mandatory imprisonment to a criminal defendant based on a fact the defendant did not know. In my view, that extraordinary result contravenes the traditional presumption of mens rea long applied by the Supreme Court."

It is doubtful that Donald Trump, a "law and order" advocate who is not keen on due process or other legal niceties, understands the importance of the principles that might lead a judge to side with a bank robber or a member of Al Qaeda. But it is reassuring that the president's leading choice for the Supreme Court does.