Crashes Caused by Negligence Are Still Accidents

The movement to stop calling car crashes "accidents" blurs an important distinction.

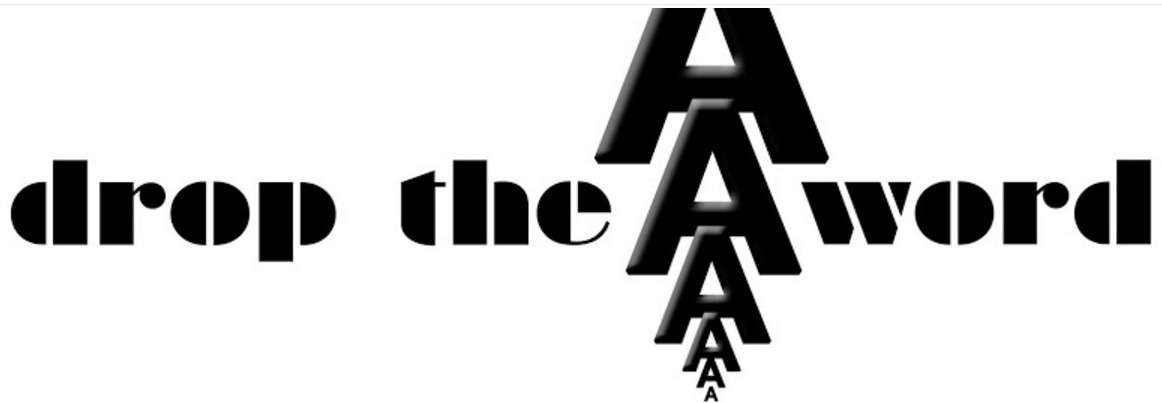

Jeff Larason, the Massachusetts highway safety director, wants journalists and public officials to stop calling car crashes "accidents," because he thinks that term lets drunk, drugged, or otherwise negligent drivers off the hook. Larason, who promotes this message through a blog and a Twitter account called "Drop the 'A' Word," recently scolded me for using the words collision, crash, and accident interchangeably in a blog post about marijuana and driving. "Drugged crashes are not 'accidents,'" he tweeted, noting that the Associated Press (in response to lobbying by Larason and his allies) now recommends that "when negligence is claimed or proven," reporters should "avoid accident, which can be read as exonerating the person responsible."

No doubt the word can be read that way, but that is not what the word means. It means only that a crash was unintentional, not that it was unavoidable or did not involve negligence.

Larason selectively quotes dictionary definitions of accident to make his case. "On Facebook," The New York Times notes, "he posted a Merriam-Webster definition that describes accident as 'an unexpected happening' that 'is not due to any fault or misconduct on the part of the person injured.'" But it's clear from the full Merriam-Webster definition that accidents involving negligence are still accidents:

1 a: an unforeseen and unplanned event or circumstance

b: lack of intention or necessity: chance <met by accident rather than by design>

2 a: an unfortunate event resulting especially from carelessness or ignorance

b: an unexpected and medically important bodily event especially when injurious <a cerebrovascular accident>

c: an unexpected happening causing loss or injury which is not due to any fault or misconduct on the part of the person injured but for which legal relief may be sought

d: used euphemistically to refer to an involuntary act or instance of urination or defecation

3 a nonessential property or quality of an entity or circumstance <the accident of nationality>

Note that definition 2(c), the part quoted by Larason, refers to an incident where the injured party is not at fault "but for which legal relief may be sought," meaning that someone else is (at least arguably) at fault, as when a pedestrian slips on an icy sidewalk that a property owner was supposed to keep clear. So even the definition Larason prefers does not support his claim that "drugged crashes are not 'accidents.'" Definition 2(a)—"an unfortunate event resulting especially from carelessness or ignorance"—obviously does not help him either. Neither do definitions 1(a) and 1(b), which hinge on whether the event was foreseen, planned, intended, or necessary.

"We hear a lot from reporters who defend use of the word 'accident' by saying that no one crashes intentionally," Larason writes in a blog post. "But let's look at the definition." In that post he focuses on the top result you get when you Google "accident definition":

ac·ci·dent

1. ?an unfortunate incident that happens unexpectedly and unintentionally, typically resulting in damage or injury.

2. ?an event that happens by chance or that is without apparent or deliberate cause.

Larason argues that "drunk, drugged, negligent, and criminal driving crashes are not unexpected." While "a driver may not intend to crash," he says, "the resulting crashes, and the tragic results, are wholly predictable." At a macro level, yes, but the point is that the driver does not expect or intend to crash. By Larason's logic, when an elderly woman falls in the shower and breaks her hip, that is not an accident either, because it is "wholly predictable" that elderly women who take showers will fall and break their hips.

Larason also argues, referring to definition 2, that "the causes of most crashes are apparent," since "there is little doubt when a driver is drunk, drugged, distracted and/or speeding as to the cause." But lack of an apparent cause is not a necessary part of definition 2, which applies to an event that happens by chance, an event that has no apparent cause, or an event that was not deliberately caused.

No matter how much Larason pushes his own idiosyncratic definition of accident, it makes perfect sense to talk about accidents caused by motorists who speed, recklessly change lanes, text while they're driving, fall asleep at the wheel, or drive while impaired by alcohol or other drugs. By contrast, it does not make sense to talk about accidents caused by drivers who deliberately run down pedestrians or commit suicide by crashing into brick walls.

Mark Rosekind, head of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, agrees with Larason that accident should be replaced by crash. "When you use the word 'accident,'" he told the Times, "it's like, 'God made it happen.'"

Maybe Rosekind and I have fundamentally different worldviews, because when I hear accident, I think, "Somebody screwed up." Often the screwup is clear enough that one driver is deemed to be at fault, in which case his insurer covers the damage. Sometimes the screwup gives rise to a lawsuit, which may or may not be successful at pinning the blame on one party. And sometimes the screwup is reckless enough (or the consequences serious enough) that it's treated as a crime. Even then, however, the defendant is charged not with purposely causing a crash but with intentionally doing something (such as getting drunk) that increased the odds of a crash.

I realize that some readers, including relatives of people killed in crashes caused by reckless drivers, see accident as an inadequate or even offensive description of such an incident. It is nevertheless an accurate description, and insisting otherwise obscures the important distinction between hurting people on purpose and hurting them unintentionally.