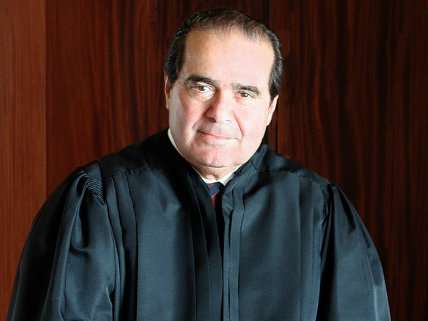

Antonin Scalia Was a Great Jurist for Criminal Defendants

The Supreme Court Justice's opinions often favored the accused-because their rights were in the Constitution.

"I ought to be the darling of the criminal defense bar," Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia once said. "I have defended criminal defendants' rights'"because they're there in the original Constitution'"to a greater degree than most judges have."

Many criminal defense lawyers might gag at the thought. After all, Scalia was the most vociferous defender of the death penalty, even pushing (in losing causes) for its application to minors and the mildly mentally retarded. He wrote the majority opinion that upheld a grotesquely disproportionate drug mandatory minimum sentence from an Eighth Amendment challenge.

Yet Scalia was not delusional. He believed his opinions in those cases were well grounded in the text of the Constitution. After all, capital punishment is mentioned specifically in the Constitution and thus cannot now be considered unconstitutional As for mandatory sentences, the use of prison, even for lengthy terms, would not have struck the Framers as both "cruel" and "unusual," as the Eighth Amendment required. Thus, Scalia's originalist approach led to unhappy results for criminal defendants in these cases.

Yet other Scalia opinions, also rooted in "the original Constitution," favored criminal defendants and were cheered by the defense bar. Indeed, in many cases Scalia sounded like a full-throated civil libertarian. Most famously, Scalia voted to protect American flag-burning protestors from criminal punishment, even though, he later admitted, he had no love for the "scruffy, bearded, sandal-wearing people" who did such things.

Scalia is rightly credited with single-handedly reviving the Sixth Amendment's guarantee that "[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right…to be confronted with the witnesses against him." Before Scalia joined the Court, it had held that out-of-court statements could be used against a defendant if they were deemed reliable. Scalia convinced his colleagues that the guarantee made by the Framers is greater than that and gives the accused the right to confront witnesses and cross-examine their testimony.

Scalia also stood strong in defense of Americans' Fourth Amendment guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures. In Maryland v. King (2013), for example, Scalia disagreed with the Court's conservatives about the constitutionality of a Maryland law allowing law enforcement to take DNA by mouth swab of anyone charged with a violent crime.

In a typically stirring dissent, Scalia argued the Fourth Amendment prohibits Maryland from conducting such suspicionless searches. "Solving unsolved crimes is a noble objective," he wrote, "but it occupies a lower place in the American pantheon of noble objectives than the protection of our people from suspicionless law-enforcement searches."

Perhaps the public would be made safer if the government were allowed to take minimally invasive DNA samples from anyone who flies on an airplane or applies for a driver's license, Scalia wrote, "But I doubt that the proud men who wrote the charter of our liberties would have been so eager to open their mouths for royal inspection." Liberal privacy expert Jeffrey Rosen said Scalia's opinion was "not only one of his own best Fourth Amendment dissents, but one of the best Fourth Amendment dissents ever."

Scalia sided with criminal suspects (and the Constitution) in several other search cases. For example, he prevailed in blocking law enforcement's use of modern technology, such as thermal imaging to search a house for contraband or a GPS monitor to track a suspected criminal's car. He strenuously dissented from a 2014 decision allowing warrantless traffic stops based on "an uncorroborated, vague, and nameless tip." Not unaware of law enforcement's interest, Scalia nevertheless concluded, "Drunken driving is a serious matter, but so is the loss of our freedom to come and go as we please without police interference."

Finally, Justice Scalia spoke out strongly against two very current criminal justice system concerns: the eroding of the Sixth Amendment's right to trial, and the tendency of Congress to criminalize everything.

Those of us who care deeply about criminal sentencing are indebted to Justice Scalia for helping ensure that a jury'"not a judge'"finds beyond a reasonable doubt all the facts that could increase a defendant's prison sentence. Scalia described this as the "the fundamental meaning of the jury-trial guarantee of the Sixth Amendment." In Sykes v. United States (2011), Justice Scalia wrote:

We face a Congress that puts forth an ever-increasing volume of laws in general, and of criminal laws in particular. It should be no surprise that as the volume increases, so do the number of imprecise laws. And no surprise that our indulgence of imprecisions that violate the Constitution encourages imprecisions that violate the Constitution. Fuzzy, leave-the-details-to-be-sorted-out-by-the-courts legislation is attractive to the Congressman who wants credit for addressing a national problem but does not have the time (or perhaps the votes) to grapple with the nitty-gritty. In the field of criminal law, at least, it is time to call a halt.

Last year'"four years after calling for an end to the overcriminalization madness'"Scalia prevailed. He wrote the majority opinion striking down the vague criminal law that aroused his ire in Sykes. The Due Process Clause, he wrote for the Court, prohibits the government from "taking away someone's life, liberty, or property under a criminal law so vague that it fails to give ordinary people fair notice of the conduct it punishes, or so standardless that it invites arbitrary enforcement."

With Justice Scalia's passing, conservatism might have lost its best friend on the Supreme Court. But all of us who believe in the rights of the accused lost a good friend, too.

Kevin Ring is the vice president of Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) and editor of Scalia Dissents: Writing of the Supreme Court's Wittiest, Most Outspoken Justice. His new book, Scalia's Court, will be published by Regnery in April.