At SCOTUS, Today's Dissent Can Become Tomorrow's Majority Opinion

Examining the role of dissenting opinions in U.S. legal history.

Writing at The New York Times, liberal legal pundit Dahlia Lithwick favorably reviews the intriguing new book Dissent and the Supreme Court by legal historian Melvin Urofsky. "According to his central thesis," Lithwick notes, "a dissent can become important, can indeed shape the future, when it becomes part of the larger 'constitutional dialogue.' Urofsky's concern here is for the 'canonical or prophetic' dissents that go on to shape the future deliberations of the justices, their successors and the American public."

What a great premise for a book about SCOTUS. One of the more under-appreciated themes in American legal history is that today's dissenting opinion can become tomorrow's majority opinion. One of my favorite examples of this phenomenon occurred as a result of the momentous 1873 decision known as The Slaughter-House Cases. At issue was a Louisiana law granting a private corporation the exclusive monopoly power to operate a central slaughterhouse for the city of New Orleans. According to local butchers, this act of state-sanctioned cronyism violated their rights to economic liberty under the recently ratified 14th Amendment, which forbids the states from passing or enforcing any law which abridges the privileges or immunities of U.S. citizens. Slaughter-House would be the first 14th Amendment case heard by the Supreme Court.

Writing for the 5-4 majority, Justice Samuel Miller turned the constitutional text on its head by claiming that the 14th Amendment actually placed no meaningful limits on state power and offered no meaningful protection for individual rights against state regulation. To hold otherwise, Miller wrote, would make the Supreme Court "a perpetual censor upon all legislation of the states."

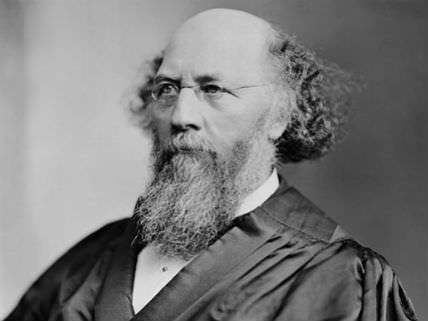

The principal dissent in Slaughter-House was filed by Justice Stephen Field, a Lincoln-appointee who became one of the Court's most important voices in favor of property rights and economic liberty. Field challenged Miller on every point. "It is to me a matter of profound regret that [the monopoly's] validity is recognized by a majority of this court," Field wrote, "for by it the right of free labor, one of the most sacred and imprescriptible rights of man, is violated." In Field's view, "the fourteenth amendment does afford such protection, and was so intended by the Congress which framed and the states which adopted it."

The strength of Field's dissent (and the weakness of Miller's majority opinion) was recognized immediately. In fact, some courts began treating Field's dissent as if it was the majority opinion.

In 1886, for example, a federal circuit in California cited Field's Slaughter-House dissent when it struck down an ostensible public health regulation whose true purpose was to prevent Chinese immigrants from operating laundry businesses within the city of Stockton. "No one can in fact doubt the true purpose of this ordinance. It means, 'The Chinese must go,'" the court declared in In re Tie Loy. Yet that sort of government overreach, the court held, violated the right to labor in an "honest, necessary, and in itself harmless calling," one of the very rights (as Field explained in Slaughter-House) that the 14th Amendment was written and ratified to protect.

A little over a decade later, the Supreme Court itself came around to Field's point of view when it started protecting the 14th Amendment right to liberty of contract in a variety of cases. This Field-ian judicial protection of economic liberty lasted until the New Deal Supreme Court rejected liberty of contract outright in 1937.

Even with the loss of liberty of contract, however, Field's Slaughter-House dissent still shapes our law today. When the Supreme Court protected the 14th Amendment right of married couples to obtain and use birth control devices in 1965's Griswold v. Connecticut, for instance, the Court was following Field's individualist reading of the 14th Amendment—and repudiating Miller's pro-government alternative. The same thing can be said of the Court's 2003 decision striking down Texas' notorious ban on "homosexual conduct." Both of those cases rest on a libertarian foundation that says fundamental rights trump state regulatory power under the 14th Amendment.

All of which raises an interesting (and perhaps unsettling) question: What modern dissent will turn out to be the law of tomorrow? Will it be Justice Clarence Thomas' stirring dissent from the Court's eminent domain abuse in Kelo v. City of New London? Or will it be Justice John Paul Stevens' rejection of the Second Amendment in his dissent from District of Columbia v. Heller? Time will tell.