Connecticut Drug Law Imposes a Three-Year Mandatory Minimum for Living in Hartford, New Haven, Bridgeport, or Waterbury

Forty-eight states have laws that designate so-called drug-free zones, boosting penalties for drug offenses committed within a certain distance of locations where children congregate. These laws are supposed to keep drug dealers away from kids, but in practice they impose extra punishment based on geographical happenstance. Connecticut's law, which creates enhanced sentencing zones within 1,500 feet of schools, day care centers, and public housing, may be the clearest example of such arbitrariness. As a new report from the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) points out, "these zones are so large that they blanket entire cities, leaving no uniquely protected areas." The upshot is "an unfair two-tiered system of justice based on a haphazard distinction between urban and rural areas of the state."

Under Connecticut's law, manufacturing, transporting, distributing, selling, or possessing with intent to sell drugs within a zone triggers a three-year mandatory minimum sentence in addition to the standard penalty. The law also imposes a one-year mandatory minimum for possessing drug paraphernalia within 1,500 feet of a school and a two-year mandatory minimum for possessing drugs within 1,500 feet of a school or a day care center. The standard sentences and the special, zone-related sentences must be served consecutively.

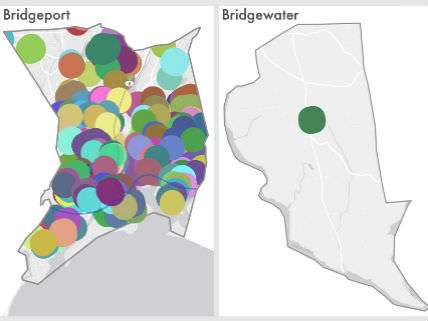

But depending on where a drug offender happens to live, those special penalties may not be so special. After mapping out the zones, PPI found that "94% of Hartford's residents, 93% of New Haven's residents, and 92% of Bridgeport's residents live in areas covered by a sentencing enhancement." By comparison, suburban and rural communities such as Prospect, Bridgewater, Union, and Canaan have just one or a few zones, covering a small percentage of their territory.

Within cities, PPI argues, "Connecticut's sentencing enhancement zones cannot deter drug activity because they are both pervasive and imperceptible on the ground." Furthermore, cases where enhancements apply almost never involve minors, whose protection is the rationale for the zones:

The Legislative Program Review & Investigations Committee looked at a sample of 300 sentencing enhancement zone cases and found only three cases that involved students, none of which involved adults dealing drugs to children. The Committee explained: "In one case, a police officer observed a group of students sitting outside the school smoking marijuana. In two cases, school officials called police to the school in response to information that students were selling drugs on school property. Except for those three cases in which students were arrested, all arrests occurring in 'drug-free' school zones were not linked in any way by the police to the school, a school activity, or students. The arrests simply occurred within 'drug-free' school zones." All of the other 297 cases in the legislature's sample involved only adults.

PPI recommends abolishing the zone-based sentences, since other laws can be used to enhance penalties in cases that actually involve minors. If that proves politically unfeasible, it says, the legislature should at least consider making the zones smaller, reducing the number of "protected" locations, and exempting drug offenses inside private residences.

Back in 2006, I noted that "in New Haven the only substantial piece of land not covered by a drug-free zone is the Yale University golf course." New Jersey is years ahead of Connecticut in recognizing the injustice of location-based drug sentences.