Two Governors Kick Off 2019 With Big Occupational Licensing Reforms

A new law in Ohio and an executive order in Idaho require state lawmakers to take a more active role in overseeing occupational licensing boards.

Two Republican governors got the new year off to a productive start by striking a small blow against their states' occupational licensing boards.

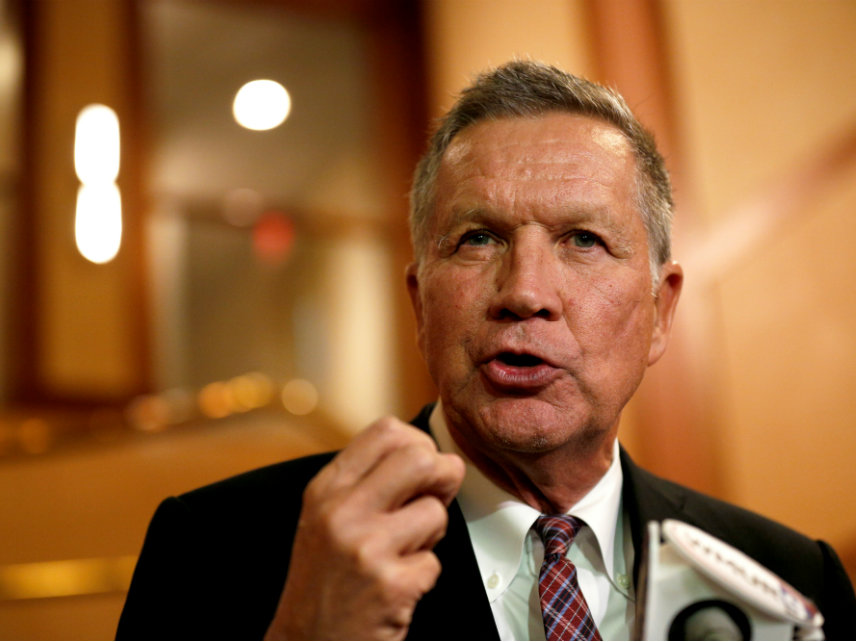

In Ohio, Gov. John Kasich signed a bill requiring the state legislature to review all licensing boards at least once every six years to ensure there is a continued public need for the licensing rules. The legislature will also be tasked with determining whether one-size-fits-all licenses are "the least restrictive form" of regulation for specific professions. If it determines that the answer is "no," the boards can be shuttered. Finally, the legislature will have to determine if a board's actions have inhibited economic growth, reduced efficiency, or increased the cost of government.

"Occupational licensing should only be a policy of last resort," says Lee McGrath, legislative counsel for the Institute for Justice, a libertarian law firm. A 2018 analysis published by McGrath's group calculates that licensing laws cost Ohio 68,000 jobs and $6 billion in economic activity annually. "This licensing reform has the potential to create more economic opportunity and save Ohioans billions of dollars," McGrath says.

The bill also opens the door for Ohioans with criminal records to obtain licenses in some fields. More than a million residents of the state have a criminal record of some sort, and about 25 percent of all Ohio jobs were off-limits to those individuals solely because of their records, according to a recent report from Policy Matters Ohio, a left-leaning think tank.

Licensing rules that automatically disqualify individuals with criminal records continue to punish people long after they have paid their debts to society. Under the reforms that Kasich signed this week, individuals with criminal records will be able to ask licensing boards whether their specific criminal records would be grounds for denying a license before they spend time and money (sometimes years and several hundred dollars) trying to meet the qualifications.

It would be better to require licensing boards to publish a specific list of crimes for which a license application could be denied. It makes sense, for example, to prevent someone with a history of crimes against children from getting a license to be a preschool teacher, but not to keep him from being a carpenter. Still, Ohio's new law will likely help some residents of the state navigate the complex licensing process and land a job.

In Idaho, the first executive order issued by newly elected Gov. Brad Little will impose a mandatory periodic review of the state's occupational licensing boards by the state legislature, similar to the reform in Ohio. In his first "state of the state" address, Little promised to put regulatory and licensing reform at the top of his agenda.

The executive order "will deliver more jobs and economic opportunity to Idahoans, particularly our low-income friends and neighbors," says Wayne Hoffman, president of the Idaho Freedom Foundation, a free market think tank.

Idaho and Ohio join three other states—Louisiana, Nebraska, and Oklahoma—that passed similar licensing sunset provisions last year.

It would be better, of course, for states to strike many occupational licensing laws from the books entirely. A promise that the legislature will review those laws and boards every few years is only as good as the people who sit in the legislature—and lawmakers always have more interesting and politically beneficial things to do than check up on how a bunch of bureaucrats are doing.

But the mandatory sunset periods are an undeniable step in the right direction, even if only as a way to curb some of the boards' worst behaviors. It's one thing to pass a rule saying that someone needs 1,000 hours of training before he can safely use a blow dryer on a customer's scalp when you think you are the final authority on the matter. Simply knowing that you'll be subject a periodic review might put the brakes on that sort of thing. And if it doesn't, the periodic reviews give the public (and pro-liberty groups like the Institute for Justice and state-based think tanks) an open door to press for changes or at least to highlight the more problematic laws.

The reforms in Ohio and Idaho are not a guarantee that licensing boards won't continue to abuse their authority. But they tip the scales slightly toward economic freedom.

Show Comments (31)