How a Heartwarming 'Hero Flight Attendant' Meme Helps Donald Trump Deport People

A viral tale of Alaska Airlines staff saving a sex-trafficked teen turns out to be propaganda for federal immigration enforcement.

A dramatic story. A righteous cause. A timely tie-in to the Super Bowl. It's no wonder Shelia Fedrick's tale recently went viral. An Alaska Airlines flight attendant, Fedrick was on a flight from Seattle to San Francisco in 2011 when she spotted an older man with a teen girl whom she suspected of being in trouble. After communicating with the girl through a secret bathroom-note, Fedrick alerted the pilot, who alerted authorities, who were waiting at the gate when the plane arrived, according to what Fedrick told NBC News.

The story of this "hero flight attendant" and the group she represented quickly spread from tabloid outlets like the Daily Mail to the pages of The New York Times and BBC News. But each new iteration failed to produce additional facts. There was no follow-up on where the alleged trafficker had come from, what happened to him after the flight—arrest? prosecution? prison?—or data on how often law enforcement responds to in-flight staff tips. (There were also many misreports that Fedrick's tale coincided with last year's Super Bowl in San Francisco, though it happened years earlier.) Most stories mentioned Airline Ambassadors International (AAI), an organization training flight attendants on how to handle suspected human traffickers, but none dug beyond AAI's own statements about intent and impact. If they had, they would've found something far less simple, and darker, than a heartwarming human-interest story.

Friends in High Places

Fedrick's 2011 experience didn't just happen into the 2017 media by accident. Her story is part of a campaign from Airline Ambassadors International, whose staff was in Houston last week to train flight attendants ahead of the Super Bowl. Like many groups focused on the issue, AAI used the myth of a sports-related sex trafficking boom to permeate the Super Bowl news-cycle.

AAI was founded in the 1990s by Nancy Rivard, and the bulk of its efforts long revolved around providing adult escorts to children traveling for medical procedures. But beginning in 2009, the agency began a serious shift toward human-trafficking awareness. These days, AAI gives presentations to airline and airport staff around America and abroad, using a training program approved by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and the U.S. State Department. Under AAI's "Blue Lightening Protocol," flight attendants who suspect someone of being trafficked are told to radio the upcoming airport and provide info directly to a DHS Tip Line, but not engage with the potential suspect or victim directly, nor "display any unusual concern or alarm."

What manners of in-flight behavior might warrant flight attendants taking action? "Children and young women traveling alone" are one sign of sex trafficking, says AAI in a training module. People who seem "nervous," appear "afraid of uniformed security," or wear "inappropriate clothing" should also trigger alarms. Likewise people who claim to be adults but have "adolescent features," and adults claiming to be the relative of a young traveler.

"I have personally witnessed how quickly law enforcement responds to the calls by flight attendants," Deborah Sigmund, co-founder and president of anti-human-trafficking group Innocence at Risk, has said. "When reports come in to the hotline, [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] agents come immediately to meet the plane as it reaches the ground."

There might be a reason for that: Innocence at Risk's other co-founder, Sandra Fiorini, was married to Alonzo Peña, a former deputy director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and DHS Attaché in Mexico. Peña is credited as the driving force behind Homeland Security's Border Enforcement Task Force (BEST), which brought together state, local, and federal officers to address security on the Southwest border. Innocents at Risk and AAI now work together on training and initiatives, and both work closely with ICE, CBP, and other DHS agencies. They're also frequent collaborators with U.S. legislators such as Reps. Chris Smith (R-NJ), Barbara Comstock (R-Virginia), and Jackie Speier (D-California), all of whom received awards at AAI's annual reception last September.

The 2016 reception was held in D.C.'s newly opened Trump International Hotel and hosted by Joe David, author of The Infidels (a novel about Christians being "brutally slaughtered" by Muslims) and Chris Hansen, former host of NBC's sex-sting show To Catch a Predator and an AAI board member.

"Perhaps the high point was during a special VIP tour led by Michael Damelincourt, managing director of Trump International Hotels, in which a handful of VIPs watched Daniel Mahdavian, director of food and beverages, amazingly de-cork a magnum of Veuve Clicquot Champage with a saber," says the AAI website. "Monies raised at this important gathering will be used to support the work of Airline Ambassadors and provide more trainings at airports throughout the U.S. on human trafficking awareness," and Trump International Hotel staff would also be trained.

The reception was sponsored by Trump Hotel, Choice Hotels, Bobby Burchfield (a lawyer who represented George W. Bush in the Florida recount and was recently hired by the Trump company), American and United Airlines, and several D.C. investment-banking, public-relations, and consulting firms. Guests included Innocence at Risk's Sigmund; Denise Mitchem, director of strategic partnerships for the National Diversity Coalition for Trump; and Henry Marx, co-founder of intelligence consultancy Norse, a group most well-known recently for its biased report on Iran's cyber capabilities.

If You See Something…

The hero of all this hoopla, 49-year-old Shelia Fedrick, has been an Alaska Airlines flight attendant for 10 years. She also lists model and actress on online resumes and talent-portfolios. Beyond this, Fedrick has little online trail, and my attempts to reach her this week were unsuccessful.

NBC notes that the girl in Fedrick's story is now in college, but it does not say what happened to her alleged trafficker. Whatever happened to him, the dramatic incident received little public attention in 2011. While the news that year is full of stories about a man arrested at the San Francisco International Airport for wearing baggy pants, plus stories about local efforts to stop sex trafficking, none mention a human trafficker apprehended at a Bay Area airport that year. The San Francisco Police Department's (SFPD) web archives turn up similarly scant results. And nothing fitting the description is mentioned in a statewide 2012 report about successful anti-trafficking efforts in the previous year.

When the Super Bowl was held in San Francisco, in 2016, the airport teamed up with Airport Ambassadors International and others for employee training on human trafficking awareness. None of the materials promoting this event mention any previous trafficking busts at the airport based on flight-attendant tips. Similarly, the DHS made a big production of standing up to human trafficking in San Francisco during last year's Super Bowl, including efforts to train airline and airport staff on stopping it, but these materials also failed to mention a previous airline-assisted trafficker bust in the area.

DHS did, however, note the new slogan for its Super Bowl-related campaign: "If you see something, say something." It's the same message Fedrick emphasizes at the end of her NBC segment.

Building an Air-to-ICE Pipeline

The lack of a public trail related to Fedrick's suspect certainly doesn't mean her story didn't happen. But it does suggest it wasn't quite the big-time catch it's being portrayed as. Perhaps it was even a big misunderstanding—a teen traveling with her dad, a young but adult woman traveling with an older boyfriend, someone else writing back on that bathroom note. Or perhaps Fredrick really did save a teen in danger, but authorities botched the case somehow. We can't know, because no one will provide any specifics, nor even confirm or deny that the incident occurred. The SFPD told me to contact the airport about it; the airport never got back to me. Alaska Airlines took two days to tell me that out of respect for customer privacy, it couldn't provide any comment.

Still, AAI representatives, federal lawmakers, online activists, and others are comfortable calling for more laws encouraging everyone to play catch-a-trafficker, regardless of whether there's evidence that these programs are effective, and without thought to the ways they could backfire. Programs asking people to profile criminals have a notoriously bad record, from New York City's stop-and-frisk to terror-thwarting work by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), another agency under Homeland Security's umbrella. Newly released TSA records obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union show previous "behavior detection" techniques weren't effective at detecting bad behavior but did lead to screenings and detainment based on racial and religious profiling.

Although a 2016 law already mandated that U.S. flight attendants be trained on spotting trafficking victims, "Rivard and Fiorini continue to lobby Congress for better awareness training for flight attendants," according to NBC News. It's unclear how their legislation would differ from the similar legislation passed last year, except to favor or fund the use of AAI and Innocence at Risk training techniques and protocols. AAI has recently been promoting an app, TIP Tools, that allows airline attendants and anyone else to easily report suspicious activity to Homeland Security. TIP Tools users can send their location, pictures, videos, and texts directly to federal agents, and AAI encourages people to use the app rather than confronting those suspected of being in trouble.

Some of the things flight-staff are being told to watch for—young women traveling solo, young women traveling with older men, women in "inappropriate clothes," people with little luggage, etc.—are incredibly common. Other things may read odd at first but have far less sinister explanations than human trafficking. A woman deferring to a male companion when interacting with airline staff, for instance, could signal a language barrier, religious/cultural tradition, a run-of-the-mill controlling relationship, or a woman who gets bad motion sickness on planes. Someone seeming "drugged" may have just taken a pre-flight Ambien. Kids who can't tell some airline employee where they're flying may have been taught not to talk to strangers.

What it comes down to is people encouraging flight personnel (or maybe anyone traveling) to report people to federal authorities, based on a broad range of harmless behavior, as a first line defense against human trafficking. "One part of our training, and it's the difficult part, but once we report it, we're supposed to let it go," Andrea Hobart, an Airline Ambassador trainer and Alaska Airlines flight attendant, told NBC. "Even though it's hard to let it go, you transfer it into the hands of the authorities and they'll pursue the case."

But if history and human nature are any indication, most of these sex-trafficking tips will turn out to be wrong. There's little evidence of U.S. sex traffickers flying victims in or around by commercial plane, and less still of strangers anywhere (on planes, at hair salons, or in any of the other locations where the federal government has been encouraging trafficking awareness) successfully spotting traffickers or trafficking victims based on brief, generic encounters. What does exist, however, is a long history of people using see-something-say-something policies to profile innocent folks as criminals based on stereotypes, to sic police on adult sex workers, and to give authorities—from local cops to child protective services to FBI agents—pretense to stop, search, and interrogate those found suspicious for any manner of trivial, bigoted, misinformed, or random reasons.

At airports, this attention is likely to fall hardest on people from certain regions, religions, or ethnic groups—especially considering our current political climate—though anyone found with a personal cannabis stash in their suitcase, a parole infraction somewhere, the potential to be engaged in sex work, or a general bad attitude may wind up with trouble.

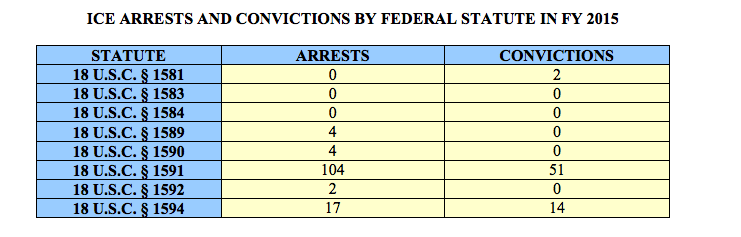

A Trump administration and Jeff Sessions-led Justice Department may bode especially badly for matters of law, order, and borders, but federal immigration agents have already been doing a fair amount of big-tent policing under the guise of fighting human trafficking. According to data presented to Congress by the U.S. Attorney General's Office last June, ICE pursued 1,034 investigations "with a nexus to human trafficking" in government fiscal-year 2015, leading to more than 1,437 arrests domestically and internationally, 752 federal indictments, and 587 convictions. But just 104 of these federal arrests were on sex-trafficking charges, and ICE-led investigations led to just 51 convictions on federal sex-trafficking charges that year. Two people were convicted on federal offenses for involuntary servitude, and 14 for conspiracy to commit human trafficking.

We cannot, in our zeal to stop sexual exploitation (or to tell and share clickbait stories), be blind to the very real harms posed by exposing all sorts of innocent people to unnecessary scrutiny from federal law-enforcement and immigration authorities. While the people behind Airline Ambassadors International, Innocence at Risk, and their ilk may be well-intentioned, the people they're working with have different agendas.

Show Comments (61)