Obama's Last-Minute Cuba Change Scrambles Immigration Politics, Disrupts Lives

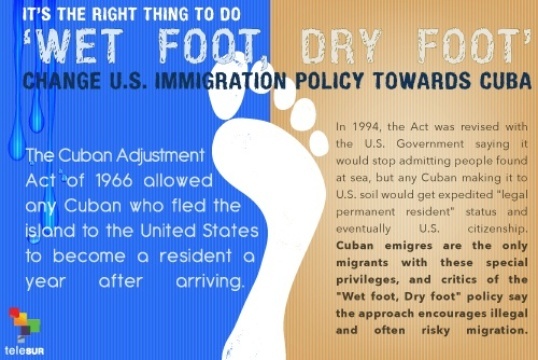

Eliminating 'Wet Foot/Dry Foot' has been a longtime goal of immigration reformers and restrictionists alike, though Cuban-Americans remain split.

It's not every day that an immigration decision made by President Barack Obama draws praise both from liberalizers such as Sen. Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) and restrictionists like the Federation for American Immigration Reform, yet that's precisely what happened after yesterday's abruptly announced policy change to end the decades-old "Wet Foot/Dry Foot" policy of giving Cubans who manage to arrive on American soil automatic residency, access to welfare, and a pathway to citizenship. The White House also terminated the Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program, which had allowed Cuban doctors who are conscripted by their government to work in a foreign country to defect. As Obama worded it in his statement,

Effective immediately, Cuban nationals who attempt to enter the United States illegally and do not qualify for humanitarian relief will be subject to removal, consistent with U.S. law and enforcement priorities. By taking this step, we are treating Cuban migrants the same way we treat migrants from other countries. The Cuban government has agreed to accept the return of Cuban nationals who have been ordered removed, just as it has been accepting the return of migrants interdicted at sea.

FAIR issued Obama a congratulatory press release, saying that "In his final week in office we are pleased to be able to say for once that he has acted wisely." Flake, who has long championed both immigration reform and an opening up of U.S.-Cuba relations (read his interview with Reason on these subjects from a year ago in Cuba), told Politico that "Individuals on both sides of the U.S.-Cuba debate recognize and agree that ending 'wet foot, dry foot' is in our national interest," and added:

It is a win for taxpayers, border security, and our allies in the Western Hemisphere. It's a move that brings our Cuba policy into the modern era while allowing the United States to continue its generous approach to those individuals and refugees with a legitimate claim for asylum.

President-elect Donald Trump has yet to weigh in on the proposal, but as I pointed out in an L.A. Times op-ed 11 months ago, he had been critical of Cubans' special immigration status on the campaign trail:

"I don't think that's fair. I mean why would that be a fair thing?" Trump responded [to a question from the Tampa Bay Times]. "I don't think it would be fair…. You have people that have been in the system for years [waiting to immigrate to America], and it's very unfair when people who just walk across the border, and you have other people that do it legally."

In later interviews he was more non-committal, saying he needed to consult more with Cuban-Americans. And what are those emigres and their families saying? As with many aspects of U.S.-Cuba policy, the reaction is mixed, though largely sorted along partisan lines.

For example Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), who had previously introduced legislation changing Cuba policy to require that immigrants prove they are political refugees ("We have people living in Cuba off Social Security benefits," he said while running for president. "They never worked here….This is an outrageous abuse"), was nevertheless largely negative about Obama's move, because it's part of a Washington-Havana rapprochement that Rubio despises:

"While I have acknowledged the need to reform the Cuban Adjustment Act for some time now, the Obama administration's characterization of this change as part of the ongoing normalization with the Castro regime is absurd," Rubio said on Thursday. "It is in fact President Obama's failed Cuba policy, combined with the Castro regime's increased repression, that has led to a rise in Cuban migration since 2014."

That last bit is certainly true, though Rubio left out two other important factors: Many Cubans now have more money to travel (thanks to the U.S. easing on remittances, and the Cuban easing on private-sector activity), and Raul Castro lifted his dictatorship's longstanding exit-visa requirement. Still, the sharp spike in Cuban immigration across the Mexican border the past two years has been an advertisement for the unintended consequences of oftentimes arbitrary, country-by-country immigration micromanagement from Washington.For instance, a Sun-Sentinel investigation in October 2015 found that Wet Foot/Dry Foot was indeed leading to the kinds of welfare-state abuses that Rubio, other elected Cuban-Americans, and immigration restrictionists have all vowed to combat:

Cubans' unique access to food stamps, disability money and other welfare is meant to help them build new lives in America. Yet these days, it's helping some finance their lives on the communist island.

America's open-ended generosity has grown into an entitlement that exceeds $680 million a year and is exploited with ease. No agency tracks the scope of the abuse, but a Sun Sentinel investigation found evidence suggesting it is widespread. […]

The U.S. has continued to deposit welfare checks for as long as two years after the recipients moved back to Cuba for good, federal officials confirmed.

Of course, unintended consequences can flow in the opposite direction as well: As this Washington Post analysis argues, the human result of the new rules—which were effective immediately; click here to read about the last Cuban admitted, and here to hear from those who didn't make the cutoff—will be to ratchet up the degree of difficulty in crossing the border, and exacerbate an already groaning illegal immigrant/asylum-seeking burden:

[Cubans] will probably do what tens of thousands of Central American migrants do now: wade across the Rio Grande, wait for the Border Patrol vans to arrive, and ask for asylum, citing a fear of persecution if sent home.

Unlike migrants from Mexico, the U.S. can't quickly turn them back. They must be detained, processed and have their claims adjudicated. In theory, this should happen quickly. In reality, it often takes years.

There is a basic fairness/equality rationale for Obama's restriction that makes intuitive sense: At this point, why not treat migrating Cubans like Venezuelans? Particularly if you can find a way from shipping political dissidents back into the arms of their persecutor. But coupled with the incoming Trump administration's planned crackdown on illegal border crossings, tightening of refugee screening, and reductions in legal immigration, the demise of Wet Foot/Dry Foot is likely to drive migrants into ever-more-dangerous black markets, and add massive stress on any section of U.S. immigration policy that looks like a loophole.

As ever, the best way to reduce illegal immigration is to increase the legal stuff. But that's a lesson the new administration will likely never learn.

Show Comments (92)