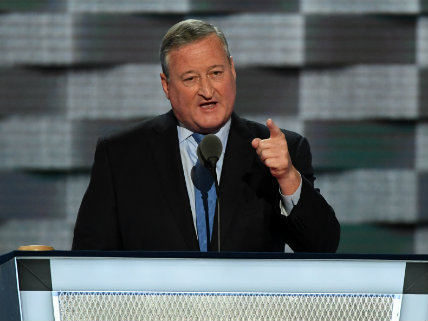

Philly Mayor Blames 'Price Gouging' for Outrage Generated by City's New Soda Tax

Businesses are passing along the cost of the tax to consumers, because that's how taxes work. Someone get Jim Kenney an economics textbook.

After driving up the cost of soda and other sugary drinks with a new tax, the mayor of Philadelphia is now trying to blame businesses for charging higher prices (and for the outrage those prices have generated).

Mayor Jim Kenney, who proposed the soda tax and championed its passage through city council last year, told reporters on Tuesday it's not the new 1.5-cents-per-ounce tax that's making it more expensive to buy a can of Coke in Philly. No, according to the mayor, those higher prices are caused by city businesses price gouging their customers in order to stir up opposition to the tax.

"They're gouging their own customers," Kenney said, KYW News reports.

To understand Kenney's reasoning, you have to know that the new tax technically is applied at the wholesale level. That is, the city is charging a tax on the transaction that takes place when a business, like a sandwich shop or grocery store, purchases soda (or the syrup used to make soda in a fountain) from a distributor. In the mayor's mind, it seems, distributors and retailers are supposed to eat the cost of the tax and continue selling their products at the same price as before the tax went into effect.

In the real world, those sandwich shops and grocery stores, of course, are adjusting the retail price of sugary drinks to make up for the added cost imposed by the tax. Some of them have posted signs to inform customers why drink prices have skyrocketed.

Kenney doesn't like that. He called those efforts "wrong" and "misleading" and suggested that it could be an extension of the expensive fight put up by soda companies, retailers, and even the city's Teamsters Union in a failing effort to prevent the tax from passing in the first place.

"This is what they do," Kenney told KYW News. "And they'll continue to lose because their legal case is not sound and their public case is not sound."

Kenney can fight the grocery stores and soda distributors opposed to the tax—though it was probably wrong for him to assume they would just go along with things after it passed against their wishes—but he can't fight the laws of economics.

Newswork's Katie Colaneri visited Carbonator Rental Services in Philadelphia to break down the math.

The distributors sells five-gallon boxes of syrup that can be used in soda fountains, and each box costs a retailer about $60. Thanks to the city's new tax, though, retailers have to pay $57.60 in taxes for each of those boxes of syrup.

"We're not talking about a couple of bucks on a $60 item," Andy Pincus, who owns Carbonator Rental Services, told Newsworks. "We're talking about $57.60 on a $60 item. It's too big not to pass on."

Pincus says he can't absorb the tax because he makes less than $20 in gross profit—the difference between how much he paid for the box of syrup and how much he sells it for—on each box. Out of that money, he has to pay all his employees, buy gas for delivery trucks, and cover all the other costs of doing business. So, he increased the price he charges to retailers buying syrup from his business. Those retailers, who are operating under similarly small margins, are doing the same thing and increasing prices charged to consumers.

It's another story to file under the old adage, proven true again and again, that businesses don't pay taxes, people do.

In Philadelphia, Kenney either never learned that basic rule of economics, or else he's pretending he didn't.

For more reasons why soda taxes are regressive and short-sighted, in Philadelphia and anywhere else, go here.

Show Comments (206)