Congress May Have Transformed US-Saudi Relations While Overriding Obama's Veto

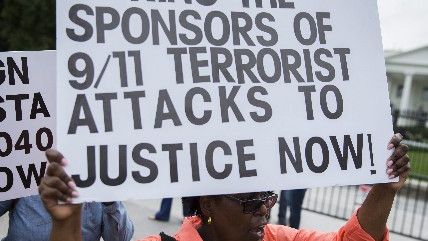

Bill allows 9/11 families to sue Saudi government, might be beginning of the end of U.S.' "special relationship" with the Kingdom.

Saudi Arabia has long been a troublesome ally for the United States.

Sure, the government has provided space for military bases, but those ended up being Osama bin Laden's top grievance with the United States. And sure, the Saudis have been helpful in cracking down on some violent radical Islamist groups, but they've sponsored and created just as many. And yes, they're a major trading partner in both oil and arms, but they've also been using our military support to indiscriminately kill civilians in Yemen. And of course, they're basically among the worst in the world when it comes to freedom of speech and religion, women's rights, LGBT rights, and human rights in general.

But the special relationship between the government of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United States may be forever transformed by Congress handing President Obama an overwhelming veto override yesterday—the first of his administration—on a bill that strips immunity of foreign governments and their officials from lawsuits regarding terrorism on U.S. soil.

The Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA) enjoys its robust support in Congress due to its association with 9/11—and congresspeople don't want to be seen as voting against the interests of 9/11 victims' families in an election year, just weeks after the fifteenth anniversary of the attacks.

The bill was spurred by allegations that certain Saudi government officials provided financial support to 9/11 hijackers, which were detailed in the recently-released "28 Pages" of a congressional inquiry into 9/11. But President Obama and the few dissenters of the bill in Congress have argued JASTA is too broadly written and not limited to 9/11 victims' families, and that it could also make U.S. military personnel and officials liable to legal retaliation in foreign courts.

White House press secretary Josh Earnest called Congress' override of the president's veto "the single most embarrassing thing the United States Senate has done" in decades, and that by not fully considering the consequences of the bill to diplomatic relations and military servicepeople, "Ultimately these senators are going to have to answer their own conscience and their constituents as they account for their actions today."

At least two senators who supported the bill and the veto override—Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Bob Corker (R-Tenn.) and Ben Cardin (D-Md.)—have suggested trying to "tighten up" the bill during the upcoming lame duck session of Congress by limiting the legislation only to 9/11. The Washington Post quotes Corker as saying the bill as written could end up "exporting…foreign policy to trial lawyers" and make U.S. personnel liable for lawsuits from anything to drones strikes to support for Israel's military actions.

Congressional support for Saudi Arabia was once as good as a rubber stamp, but a number of congresspeople recently made a bipartisan push to restrict a more than $1 billion arms sale to Saudi Arabia because of concerns over the Kingdom's bombardment of schools, hospitals, and civilians in Yemen. The resolution almost certainly will not have the support to stop the sale, but the pushback from Congress is new and noteworthy, regardless.

There are legitimate concerns about the reciprocal nature of laws pertaining to the liability of foreign officials, but editor emeritus of World Policy Journal David A. Andelman made some pretty weak arguments against the bill in a CNN op-ed. One of his concerns is that the Saudis could clamp down on oil production and thereby contribute to a rise in fuel prices worldwide. A fair if potentially overstated economic concern, but it assumes the Saudis would be more concerned with lawsuits than they are with their ongoing proxy war against Iran, where keeping oil prices low is in the Saudi interest.

An even worse argument Andelman makes is that American jobs could be lost if Saudi Arabia stops buying weapons from the U.S., even though the U.S. military-industrial complex is in no danger of running out of international clientele any time soon. Further, as William D. Hartung notes in Security Assistance Monitor:

Since taking office in January 2009, the Obama administration has offered over $115 billion worth of weapons to Saudi Arabia in 42 separate deals, more than any U.S. administration in the history of the U.S.-Saudi relationship. The majority of this equipment is still in the pipeline, and could tie the United States to the Saudi military for years to come.

U.S. arms offers to Saudi Arabia since 2009 have covered the full range of military equipment, from small arms and ammunition, to howitzers, to tanks and other armored vehicles, to attack helicopters and combat aircraft, to bombs and air-to-ground missiles, to missile defense systems, to combat ships. The United States also provides billions in services, including maintenance and training, to Saudi security forces.

It will take a lot more than JASTA becoming law as presently constructed for U.S.-Saudi military and economic interest to be untangled. But the fact that Congress no longer considers Saudi Arabia's government to be impervious to consequence is a development to watch closely.

Show Comments (219)