Debating NYU's Jeremy Waldron on Free Speech vs. Hate Speech on College Campuses

Why America should never join the rest of the world in enacting hate speech bans

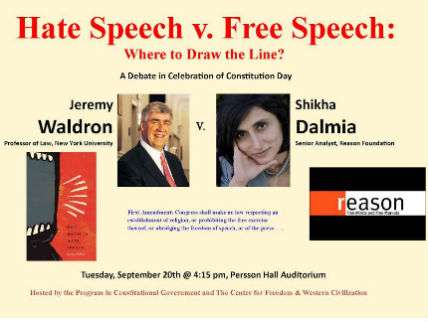

On Tuesday, I debated Jeremy Waldron, a professor of law and philosophy at New York University, on "Hate Speech, Micro-Aggression and the First Amendment: Where to Draw the Line on College

Campuses?" The debate was organized by Colgate University's Center for Freedom and Western Civilization to celebrate Constitution Day.

The only thing that exceeds Waldron's stellar credentials is his personal charm. A New Zealander, he got his doctorate in law at England's Oxford University, has written over a dozen books, gazillions of journal articles, and taught at Berkley, Princeton and Columbia. His 2012 book, "The Harm of Hate Speech," expounds what has become by far the most discussed rationale in the last eight years for banning hate speech in America. In it, he makes the radical suggestion that America needs to get over its First Amendment hang ups and enact hate speech bans to protect the "basic dignity and humanity" of minorities. He is not concerned about hurting the subjective feelings of minorities, he says, as he is about the objective harm that an environment filled with hateful signs does to their ability to operate as equal citizens in society. He asks us to imagine how a Muslim man walking with his 10-year-old daughter in New Jersey would feel if he was confronted with a sign saying: "Muslims and 9/11! Don't serve them, don't speak to them, and don't let them in." What would the man say to his daughter?"

There is more to Waldron's argument than this short description implies and Stanley Fish, the former Duke University professor who is among the most celebrated thinkers of the post-modern left, has noted that although most arguments for hate speech bans are knee-jerk and thoughtless and impulsive, Waldron's arguments are different. "They hit the mark every time."

I obviously disagree. Vehemently.

Here is my response to Waldron:

The United States faces a lot of scorn and derision in elite international forums because it is the only country, apart from maybe Hungary, that refuses to enact hate speech bans. But on this Constitution Day, let me just say that it is a very good thing that America has a strong First Amendment tradition standing athwart history yelling stop to hate speech laws. And this is not because I don't care about minorities. I do. Profoundly. After all, I am a minority in nearly every respect. I'm an immigrant from India, a person of color, lapsed Hindu-turned-atheist and, rarest of all, a political libertarian. In my view, Donald Trump's characterization of Mexicans and his anti-minority hate mongering alone ought to disqualify him from the presidency. His comb-over is the other reason.

So why do I oppose official bans on hate speech? Mainly because countries with a long history of them have done no better a job than America of protecting precisely what Prof. Waldron wants — the "basic dignity and reputation" of minorities, and a far worse job than America of protecting overall free speech rights. Lets just do a brief survey of the record:

Anti-Semitism is undoubtedly much worse in continental Europe. The same is true for Islamophobia, despite its uptick in America in the Age of Trump. It took gays longer to win their rights in America than in Europe, but not because of the absence of hate speech bans. And America's treatment of Hispanics, its dominant minority, is no worse than, say, England's treatment of Indians and Pakistanis, its dominant minority. Blacks of course have a special, complicated history in America, but America has not needed hate speech bans to make racism unrespectable in polite company.

Countries with hate speech bans don't have much to show by way of stopping hate and protecting minorities. But their record of protecting free speech is way worse than America's. Here are just a few of the many, many egregious examples:

Canada has a Human Rights Tribunal that enforces its hate speech laws that were supposed to limit themselves to prosecuting speech that incites hatred and "could lead to a breach of the peace." What is a breach of the peace? Apparently an article by Mark Steyn, a popular conservative columnist, titled "America Alone," that worried about Europe's growing Muslim population and its implications for Europe's future. The tribunal decided to prosecute both Steyn and Maclean, a highly respected magazine in Canada that published his article. Now I disagree with just about every word in Steyn's article, including "a" and "the," but hate speech? C'mon! Likewise, Britain arrested a British politician for "racial and religious harassment" because he delivered a speech quoting Winston Churchill's unflattering description of Islam.

Now, its not that Prof Waldron and other proponents of hate speech bans don't value free speech. It's just that he thinks that's not the only thing one ought to value. Making sure that minorities live in a non-hostile social environment where their basic dignity is protected is also an important social value.

It is, no doubt. But is it more important than, say, stopping, terrorism, by censoring articles on "how to make a pressure cooker bomb," something that Trump just demanded? And if Holocaust denial to protect Jewish sensibilities ought to be a prosecutable offense, why not articles by global warming deniers to prevent global climate catastrophe? Why is speech that questions such existential threats to be tolerated if hate speech is to be suppressed? How will we draw any principled limits to stop slipping down the slope of repression and censorship?

Hate speech bans are at best irrelevant and at worst worst harmful. Such worries aren't just theoretical. There is empirical evidence from the real world. Indeed, one institution in America where Prof. Waldron's ideas have been implemented are universities. On campuses, Jonathan Rauch, a gay activist and writer for The Atlantic, notes, Prof Waldron's "hostile environment doctrine has become part of the administrative furniture." Furthermore, universities are the most favorable test case for Prof. Waldron's ideas. They have an inherent interest in maintaining public spaces free of hateful or intimidating or threatening signage where everyone can learn. But they also have a special intellectual mission to engage in free and open inquiry where contrarian, uncomfortable and unconventional ideas can be thrashed out. They depend on free speech more than any other institution in society so one can expect them to be most protective of it. Furthermore, universities are run not by politicians who have to win elections but exceedingly learned and benevolent people free of crass political motives and silly prejudices. If there is any institution one could count on to draw the right balance between free speech and hate speech without slipping down the censorship slope, it is universities. So how's that been working out?

I think it's fair to say that free speech is more endangered on college campuses than anywhere else in America, although the virus is spreading.

Partly this is due to federal mandates like Title IX that require all colleges, public and private that receive federal money, to ensure gender equality on campus and, prevent sexual "harassment" – verbal and nonverbal. But partly it is of their own volitional embrace of political correctness and demands by social justice warriors who want not freedom of speech but freedom from speech.

Indeed, a new kind of campus politics scarcely imaginable 20 years ago has emerged around the "right not to be offended." It's goal is to ferret out every last vestige of sexism, racism, and all other -isms lurking in the deep structure of the human mind and turn campuses into intellectual "safe spaces." FIRE (Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, an outfit that fights for constitutional rights on campuses) has uncovered 257 incidents from 2000 to 2014 of speakers who were disinvited because of their views. Weirdly, social justice warriors have banned not only right wing speakers such as former Secretaries of State Condoleezza Rice and Henry Kissinger for perpetrating war crimes but also liberal ones such as Dan Savage, a gay rights advocate and sex columnist (because he used the word tranny for transsexual); International Monetary Fund head Christine Lagarde was disinvited by Smith College for the "strengthening of imperialist and patriarchal systems that oppress and abuse women worldwide." Regrettably but predictably, conservative students have also jumped in on the action and started disinviting leftist speakers. Some at CUNY even asked New York state legislators to ban anti-Israel protests as hate speech. It's a bipartisan game.

But the forces of political correctness want to sanitize not only the campus environment outside of class but in class as well. They are demanding trigger warnings for any course material that can upset anyone. What counts as upsetting? The Great Gatsby for its misogyny; Mrs. Dalloway because it is not feminist enough; Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for discussing slavery from a white boy's perspective. This has created such a chilling environment that junior, untenured faculty in particular have taken to omitting any controversial material from their course offerings such as Rousseau's discussion of natural gender differences in Emile, Aristotle's discussion of natural slavery in the Politics, and Nietzsche's attack on Christianity as a slave religion.

And then there are "microaggressions" – or subtle insults that unintentionally denigrate a group. What counts as microaggression? Any criticism of affirmative action, of course. But also statements like "America is a land of opportunity." "Or if you work hard you can succeed" -- because such statements "microinvalidate" the experience of marginalized groups. And a professor correcting a student for spelling indigenous with an uppercase "I."

Even George Orwell's 1984 didn't anticipate this level of thought control and censorship. How have we reached this ridiculous state of affairs? Let me list two main reasons, both of which ought to give pause to proponents of hate speech bans.

One: Hate speech bans make us impatient and dogmatic

The main reason that libertarians like me are partisans of free speech is not because we believe that a moral laissez faire, anything goes attitude, is in itself a good thing for society. Rather, it stems from an epistemic humility that we can't always know what is good or bad a priori – through a feat of pure Kantian moral reasoning. Moral principles, as much as scientific ones, have to be discovered and developed and the way to do so is by letting competing notions of morality duke it out in what John Stuart Mill called the marketplace of ideas. Ideas that win do so by harmonizing people's overt moral beliefs with their deeper moral intuitions or, as Jonathan Rauch notes, by providing a "moral education." This is how Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King and Frank Kamney, the gay rights pioneer, managed to open society's eyes to its injustices even though what they were suggesting was so radical for their times.

But this takes time. With free speech, societies have to play the long game. It takes time to change hearts and minds and one can't be certain that one's ideas will win out in the end. One has to be willing to lose. The fruits of censorship -- winning by rigging the rules and silencing the other side -- seem immediate and certain. But they unleash forces of thought control and dogmatism and repression and intolerance that are hard to contain, precisely what we are seeing right now on campuses.

Two: Hate speech bans breed self-defeating pathologies

One of the more surreal things about the campus PC movement is that it claims to be acting in the name of minorities and yet considers the First Amendment's free speech protections as an impediment to its goal. But the reason behind the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech is precisely to create a space for intellectual minorities.

So why has the First Amendment become so inconvenient for our campus warriors? It is because on campuses they are the dominant ideology and offering the courtesies required by the First Amendment to their ideological opponents has become too inconvenient. It is the classic pathology of power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

But here's the problem: They still operate in a democracy governed by majoritarian rule. Hence, to the extent that they are trying to get their way by silencing "majority" voices instead of winning them over, they are making themselves vulnerable. That's because these voices will generate counter-ideologies and vote into power those people who echo them. But when these scurrilous majoritarian ideologies emerge, with the guardrail of the First Amendment weakened, minorities will be less able to prevent majoritarian passions from pushing them overboard. Much as I hate Trump, his rise represents the revenge of the masses against political correctness.

So my question to Prof Waldron is this: If enlightened universities have failed to draw the proper balance between free speech and hate speech, what makes you think crass politicians will be able to do so? How will we prevent them from using the hate speech bans to silence legitimate dissenters or contrarian voices – or extending speech restrictions to other ends? How do we prevent the majority from coopting these bans to silence minorities and minority viewpoints, the very thing you want to protect?

Show Comments (77)