The Big Fat Lie

The government's bad info on food.

If you have even a passing acquaintance with current events, then you've probably seen a host of headlines about the ostensible revolution in dietary thinking. "Eating Fat Is Good for You: Doctors change their minds after 40 years," blared a London newspaper in 2013. "Why Experts Now Think You Should Eat More Fat," explained Men's Journal the next year.

Last month The Economist made "The Case for Eating Steak and Ice Cream." Last week Time argued that "The Case for Eating Butter Just Got Stronger." That article cited an earlier Time cover story noting that "fat had become 'the most vilified nutrient in the American diet' despite the scientific evidence showing it didn't harm health or cause weight gain in moderation."

The new dietary bugbear is sugar, now the target of "Twinkie taxes," soda taxes, and the opprobrium of public scolds everywhere.

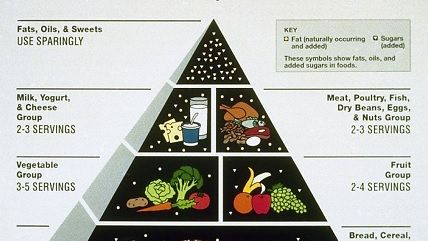

This is pretty big news, given the drumbeat of advice Americans have been receiving for so long. Starting in the 1980s the federal government's urged people to shun fats and cholesterol and load up on carbs. A 1990s food pyramid from the USDA placed bread, rice, and pasta at the base, suggesting a person eat six to 11 servings a day—but only two or three servings of meat or eggs and even less of fats.

As a long piece by Ian Leslie in The Guardian notes, "consumers dutifully obeyed. We replaced steak and sausages with pasta and rice, butter with margarine and vegetable oils, eggs with muesli, and milk with low-fat milk or orange juice. But instead of becoming healthier, we grew fatter and sicker. Look at a graph of postwar obesity rates and it becomes clear that something changed after 1980. In the U.S., the line rises very gradually until, in the early 1980s, it takes off like an aeroplane. Just 12 percent of Americans were obese in 1950, 15 percent in 1980, 35 percent by 2000."

You can't necessarily ascribe that to diet alone. Other factors, such as more sedentary jobs and lifestyles and zoning policies that required people to drive more, surely played a role. But it seems clear that official government dietary advice didn't help.

What makes that even more remarkable—and the main subject of the piece in The Guardian—is the degree to which the scientific community enforced what turned out to be erroneous dogma.

For many years, starting in the late 1950s, a British nutritionist named John Yudkin waged a lonely war against the prevailing scientific consensus. Dietary fat was not the bogeyman it was portrayed to be, he argued. The real problem, he said, was sugar. In 1972 he published a book on the topic: Pure, White and Deadly.

And for going against the scientific grain, Yudkin was thoroughly savaged by the peers in his field. Among them was Ancel Keys, who believed fat was the culprit behind heart disease and other ailments. He made lacerating attacks on Yudkin and his research, and was joined in them by entrenched interests such as the British Sugar Bureau.

"Throughout the 1960s," Leslie writes, "Keys accumulated institutional power. He secured places for himself and his allies on the boards of the most influential bodies in American healthcare, including the American Heart Association and the National Institutes of Health. From these strongholds, they directed funds to like-minded researchers, and issued authoritative advice to the nation."

Keys and his allies produced research to support their conclusions, but the work fell victim to confirmation bias: Information that undercut the fat-is-bad hypothesis was dismissed and ignored. Or, in the case of Yudkin's work, angrily shouted down.

Eventually, however, the data suggesting problems with the fat-is-bad hypothesis—such as the fact that the French eat a lot of saturated fat but have very low rates of heart disease—piled up so high that it caused nutritionists to pause and rethink, albeit slowly and with considerable resistance. But by then, Leslie writes, "Yudkin's scientific reputation had been all but sunk. He found himself uninvited from international conferences on nutrition. Research journals refused his papers. He was talked about by fellow scientists as an eccentric, a lone obsessive. Eventually, he became a scare story."

The enforcement of dietary orthodoxy is not limited to fat. The Food and Drug Administration, for example, currently is pushing the food industry to reduce salt content—even though scientists now think this is wrong: "According to studies published in recent years by pillars of the medical community, the low levels of salt recommended by the government might actually be dangerous," the Washington Post reported last April.

The parallels to other hotly debated scientific issues—climate change in particular—are obvious. An overwhelming majority of climate scientists accept the anthropogenic thesis: the notion that human activity is at least partly responsible for climate change. Like-minded researchers are lionized and blessed with research grants; skeptics are vilified as whores for the fossil-fuel industry.

Of course, just because the nutritional consensus about fat was wrong does not mean the consensus about global warming is wrong. There's an overwhelming scientific consensus about evolution and gravity, too. And evidence in favor of those theories continues to accumulate while evidence that could falsify them remains scarce as unicorns. Besides, prudence counsels restraint. Science might one day revise its view of gravity, but that doesn't make it safe to jump off bridges.

Nevertheless, the story of John Yudkin should serve as a cautionary tale about the danger of groupthink and the folly of demonizing people who dare to ask hard questions. It's crucially important that we get the facts about salt, climate change, and other possible hazards right. To that end, it's also crucially important to recognize the possibility that we might be wrong.

This column originally appeared at the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Show Comments (131)