Death Comes for Terry Pratchett

The fantasy humorist's beloved Discworld novels tackled liberty, authority, and self-ownership with a devastatingly light touch.

Terry Pratchett may not have been the first writer to personify Death as a walking, talking skeleton tasked with reaping the souls of the living, but he was the first to give him a horse named Binky and a granddaughter named Susan.

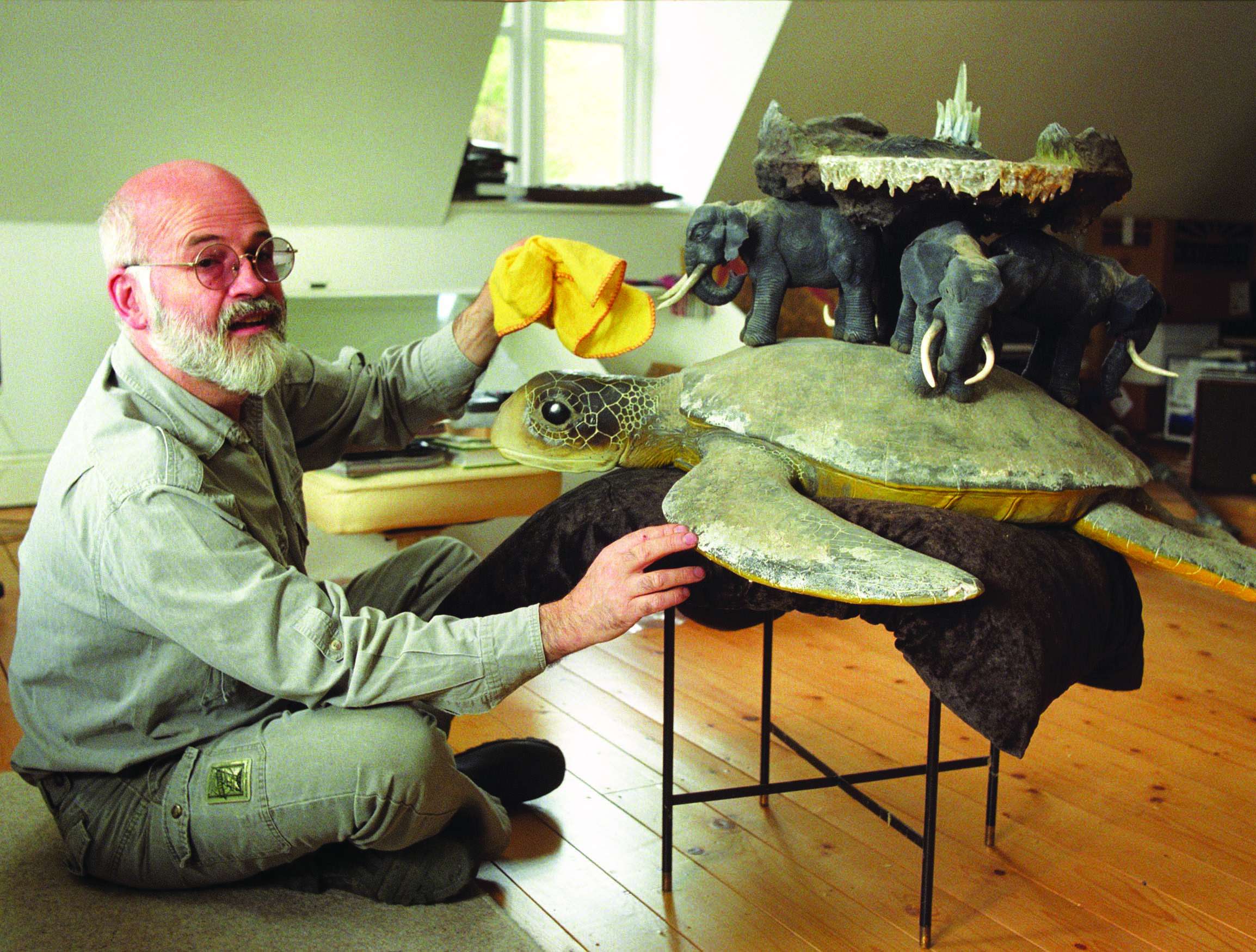

This Death was no less efficient or inevitable despite all the whimsy, of course. As various characters in Pratchett's long-lasting, wildly popular series of fantasy novels passed on, Death traveled across Discworld—a flat planet resting on the backs of four elephants who stood on a giant turtle that swam through the universe—to ferry the newly deceased to whatever came afterward.

So it was highly appropriate that after Pratchett's death at age 66 on March 12, following a long and deliberately public faceoff with early-onset Alzheimer's disease, the novelist's official Twitter account described his passing as Death gently escorting Pratchett from our rounder, less turtle-dependent world.

But let's not dwell on Death. Pratchett's Discworld books, all 40 of them (not counting short stories and related works), teemed with messy, disorganized life. And because he wrote in the fantasy genre, they were also packed with wizards, witches, dwarves, dragons, vampires, zombies, demons, werewolves, and the occasional orangutan. His books were humorous in tone, but tackled weighty matters of self-determination, identity, innovation, and, above all else, liberty.

"Whoever created humanity left in a major design flaw. It was the tendency to bend at the knee." That piece of insight came from Feet of Clay, a book from right in the middle of his series, published in 1996. The witticism encapsulates a consistent theme in his books approaching how humans (and other sentient species) struggle between the desire to be free and the comfort of letting somebody more powerful or smarter (or claiming to be smarter, anyway) call the shots. In Pratchett's books, both the heroes and the villains tended to be people in positions of authority. What separated his heroes—people like police commander Samuel Vimes, witch Esme "Granny" Weatherwax, and even Patrician Havelock Vetinari, an assassin turned ruler of the sprawling city of Ankh-Morpork—from the villains was their insistence on letting people live their own lives, whatever may come of it, even when they made a mess of things.

By contrast, Pratchett's villains, whether they were fallen and irrelevant nobles, religious leaders, narcissistic elves, or tradition-obsessed dwarves, pursued power for themselves while claiming it was for the benefit of all. The ultimate villains in Pratchett's books were the "auditors of reality," shapeless cosmic bureaucrats who hate life because it's so unpredictable. People aren't just shaped by the universe. They help reshape the universe, and this torments creatures who want nothing more than a permanent form of order. Pratchett responded (through Vetinari) to all these inclinations in The Truth: "Pulling together is the aim of despotism and tyranny. Free men pull in all kinds of directions….It's the only way to make progress."

Pratchett's works embraced progress and innovation, both in technology and in humanity. His book series may have started in what appeared to be a typical quasi-medieval fantasy milieu, but it was far from static. Over the course of his novels, the Discworld saw the invention of the printing press, a form of telegraph, paper currency, mail, and in the last book to be published before Pratchett's death, the steam engine. But also over the course of his novels, the Discworld also saw the development of concepts of liberty, like the free practice of religion, freedom of speech and of the press, and the notion that basic rights ought to be extended to new races that humanity had treated like vermin or property—goblins, orcs, golems, the undead.

As J.K. Rowling eclipsed Pratchett as England's (and ultimately the world's) most popular fantasy writer, he introduced a teen witch named Tiffany Aching in a series of young adult-oriented books sharing the DiscÂworld setting and some of its characters. Rather than replicating the concept of a repressive institutionalized public school setting and infusing it with magic, like Rowling did with Hogwarts, Pratchett sent Aching out into the world to learn from other witches and through experience how to deal with serious problems using magic (or, more importantly, not using magic). She was Harry Potter's homeschooled cousin.

Pratchett's anti-authoritarian authority figures and his themes of innovative freedom and self-determination drew him praise from the Libertarian Futurist Society. Several of his books have been finalists for the group's Prometheus Award. He won in 2003 for Night Watch, a book starring Vimes that used time travel to explore Ankh-Morpork's dark history of violent, murderous leadership and thuggish police. It even had examples of a vicious variation on waterboarding-style interrogations before the world knew how the CIA was treating certain prisoners in its efforts to track down Osama bin Laden. When accepting the prize, Pratchett encapsulated both what Vimes learned from his experience with authority turned bad and what he saw from the government today: "When lawlessness walks the streets, the authorities will bend all their efforts to keeping honest men unarmed…Policemen are sometimes tempted into being sheepdogs who prefer to keep the flock corralled rather than protect it from the predators, because it's easier to bite sheep than wolves. [Vimes] learns that the people who declare that the innocent have nothing to fear are wrong, because the innocent certainly should fear; they fear the guilty and, especially, they should fear, distrust, and fight the kind of people who say 'the innocent have nothing to fear.'"

Pratchett noted, ruefully, that England lacks a tradition of libertarianism, but went on: "Currently we have a government that lacks wisdom, perspective, or talents, is centrist, arrogant, talks incessantly about rights while it curtails freedoms, and is led by a man who is passionately devoted to appearing to be passionately devoted to things. I see fragments of Night Watch all around me. So, right now, I'm feeling very libertarian indeed."

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Death Comes for Terry Pratchett."

Show Comments (31)