Today's Pothead Is Yesterday's Cigarette Fiend

Good-for-nothing teenagers gotta smoke something.

In his 1997 book The Selfish Brain, Robert DuPont, the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, describes marijuana's impact on its users' life prospects. "Unlike cocaine, which often brings users to their knees, marijuana claims its victims in a slower and more cruel fashion," DuPont says. "It robs many of them of their desire to grow and improve, often making heavy users settle for what is left over in life…Marijuana makes its users lose their purpose and their will, as well as their memory and their motivation….[Cannabis consumers] commonly just sink lower and lower in their performance and their goals in life as their pot smoking continues. Their hopes and their lives literally go up in marijuana smoke."

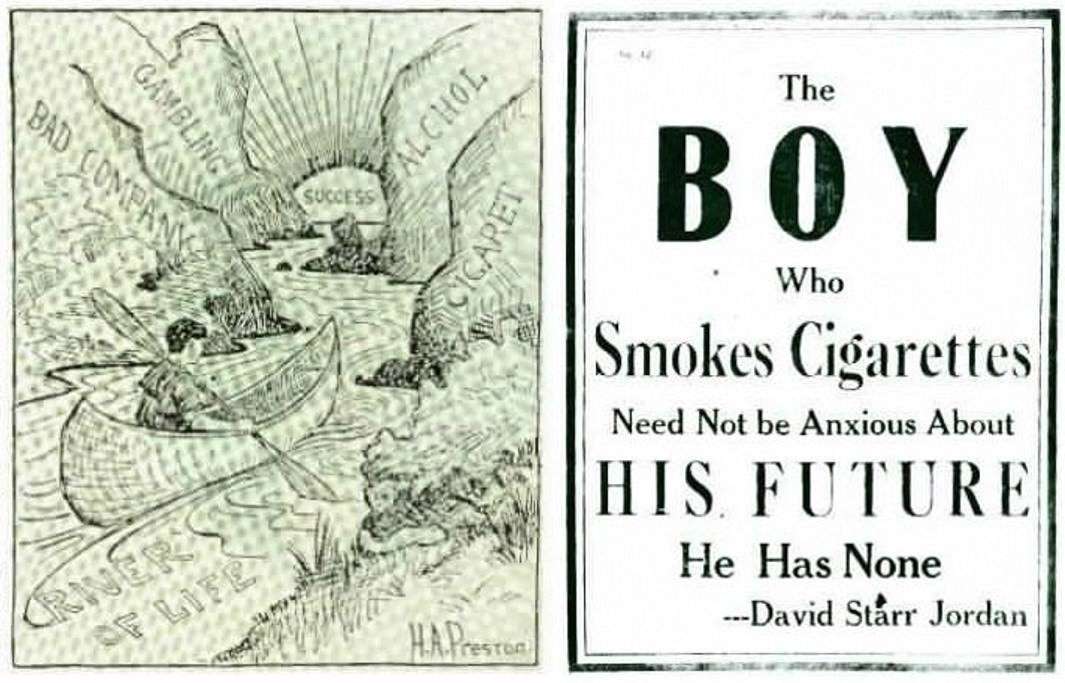

In his 2015 book Going to Pot: Why the Rush to Legalize Marijuana Is Harming America, William J. Bennett, the first director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, quotes that passage from DuPont's book in the course of arguing that cannabis is much more dangerous than commonly believed. "Has anyone alleged anything like the foregoing with tobacco use?" ask Bennett and his co-author, Robert A. White. Since they assume the answer is no, Bennett and White clearly do not realize that early opponents of cigarette smoking claimed it produced symptoms very much like those that DuPont attributes to marijuana.

According to those critics, who included celebrities such as Henry Ford and Thomas Edison, cigarettes made young people stupid, suppressed their motivation, ruined their academic performance, turned them into ne'er-do-wells and delinquents, and rendered them virtually unemployable. The striking parallels between the anti-cigarette propaganda of the early 20th century and the anti-pot propaganda that prohibitionists like DuPont and Bennett continue to disseminate suggest that responses to drug use have less to do with the inherent properties of the substance than with perennial fears that are projected onto the pharmacological menace of the day.

Although tobacco had been widely used by Americans since colonial times, cigarettes did not catch on until after production was mechanized in the 1880s. Per capita consumption of cigarettes rose nearly a hundredfold between 1870 and 1890, from less than one to more than 35. In 1900 chewing tobacco, cigars, and pipes were still more popular, but by 1910 cigarettes had become the leading tobacco product in the U.S. Per capita consumption skyrocketed from 85 that year to nearly 1,000 in 1930.

As Cassandra Tate shows in her 1999 history Cigarette Wars: The Triumph of the Little White Slaver, the rise of the cigarette caused alarm not only among die-hard opponents of tobacco but also among pipe and cigar smokers (such as Edison), who perceived the new product as qualitatively different. Critics believed (correctly) that cigarettes were more dangerous to health because the smoke was typically inhaled. They also worried that boys and women would be attracted by the product's milder smoke and low price. "The cigarette is designed for boys and women," The New York Times declared in 1884. "The decadence of Spain began when the Spaniards adopted cigarettes, and if this pernicious practice obtains among adult Americans the ruin of the Republic is close at hand."

At first the anti-cigarette campaign, which had close ties to the temperance movement, focused on restricting children's access. By 1890, 26 states had passed laws forbidding cigarette sales to minors, but many children continued to smoke. Led by Lucy Page Gaston, a former teacher from Illinois whose career as a social reformer began in the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, the anti-cigarette crusaders next insisted that complete prohibition was necessary to protect the youth of America. Between 1893 and 1921, 14 states and one territory (Oklahoma) enacted laws banning the sale of cigarettes, and in some cases possession as well.

Upholding Tennessee's ban in 1898, the state Supreme Court declared that cigarettes "are wholly noxious and deleterious to health. Their use is always harmful; never beneficial. They possess no virtue, but are inherently bad, bad only. They find no true commendation for merit or usefulness in any sphere. On the contrary, they are widely condemned as pernicious altogether. Beyond any question, their every tendency is toward the impairment of physical health and mental vigor."

In contrast to contemporary anti-smoking activists, who talk almost exclusively about the habit's effect on the body, early critics of the cigarette were just as concerned about its impact on the mind. In the 1904 edition of Our Bodies and How We Live, an elementary school textbook, Albert F. Blaisdell warned: "The cells of the brain may become poisoned from tobacco. The ideas may lack clearness of outline. The will power may be weakened, and it may be an effort to do the routine duties of life….The memory may also be impaired."

Blaisdell reported that "the honors of the great schools, academies, and colleges are very largely taken by the abstainers from tobacco," adding, "The reason for this is plain. The mind of the habitual user of tobacco is apt to lose its capacity for study or successful effort. This is especially true of boys and young men. The growth and development of the brain having been once retarded, the youthful user of tobacco has established a permanent drawback which may hamper him all his life. The keenness of his mental perception may be dulled and his ability to seize and hold an abstract thought may be impaired."

In the 1908 textbook The Human Body and Health, biologist Alvin Davison agreed that tobacco "prevents the brain cells from developing to their full extent and results in a slow and dull mind." He added, "At Harvard University during fifty years no habitual user of tobacco ever graduated at the head of his class."

These themes were taken up by prominent, widely admired Americans who were troubled by a cluster of traits that would later be associated with marijuana. "No boy or man can expect to succeed in this world to a high position and continue the use of cigarettes," Philadelphia Athletics Manager Connie Mack wrote in 1913. Biologist David Starr Jordan, the first president of Stanford University, concurred. "The boy who smokes cigarettes need not be anxious about his future," he said. "He has none."

In 1914 Henry Ford published The Case Against the Little White Slaver, which included condemnations of cigarettes from entrepreneurs, educators, community leaders, and athletes. Edison, who contributed to Ford's booklet, was repeating a widely accepted notion when he observed that cigarette smoke "has a violent action on the nerve centers, producing degeneration of the cells of the brain, which is quite rapid among boys." He added that "unlike most narcotics this degeneration is permanent and uncontrollable."

In the decades that followed, the cigarette's reputation underwent a complete reversal. Far from sabotaging intellectual achievement and economic productivity, it was seen as facilitating them through the stimulating action of nicotine. But the dull, listless underachievers described by Ford and Edison reappeared in the 1960s, smoking something else.

Testifying before Congress in 1970, Harvard psychiatrist Dana Farnsworth noted that scientists had come up with a name for the condition that prevented marijuana users from reaching their potential. "I am very much concerned about what has come to be called the 'amotivational syndrome,'" Farnsworth said. I am certain as I can be…that when an individual becomes dependent upon marijuana…he becomes preoccupied with it. His attitude changes toward endorsement of values which he had not before; he tends to become very easily satisfied with what is immediately present, in such a way that he seems to have been robbed of his ability to make appropriate choices."

A decade and a half later, Robert DuPont declared that "millions of young people are living as shadows of themselves, empty shells of what they could have been and would have been without pot." In 1989, his first year as the nation's first official "drug czar," Bill Bennett explained how smoking pot affects young people: "It means they don't study. It causes what is called 'amotivational syndrome,' where they are just not motivated to get up and go to work."

It is plausible, of course, that smoking a lot of pot in high school might interfere with academic performance, just as heavy drinking might. But Farnsworth, DuPont, and Bennett are describing something more than that: a long-lasting impairment of the will that prevents cannabis consumers from being all that they can be.

Amotivational syndrome was portrayed in several ads produced by the Partnership for a Drug-Free America during the 1980s. A memorable 1988 TV spot shows two young men smoking marijuana, one watching television, the other ridiculing warnings about the dangers of pot. "We've been getting high for, what, 15 years?" says the skeptic, "Nothing's ever happened." Then we hear the voice of his mother, asking him if he's looked for a job today. The announcer says, "Marijuana can make nothing happen to you too."

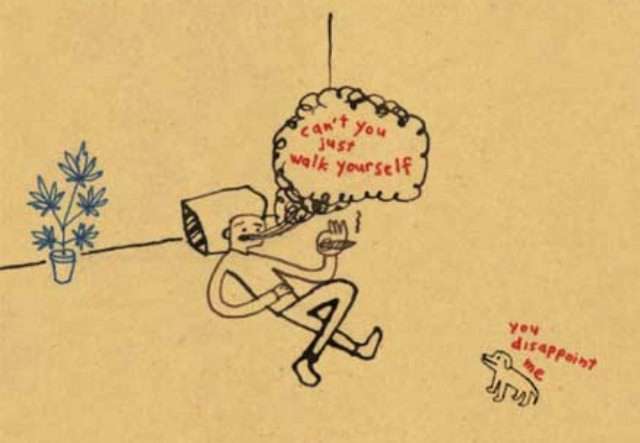

In the same vein, a print ad from the Office of National Drug Control Policy shows a pot smoker who says to his dog, "Can't you just walk yourself?" The dog, who evidently is not stoned, says, "You disappoint me." Which I guess means this guy should either stop smoking pot or get a less judgmental dog.

Despite its continuing appeal as a propaganda theme, the idea that smoking pot makes people unproductive has never been substantiated. In their 1997 book Marijuana Myths, Marijuana Facts, the sociologist Lynn Zimmer and the pharmacologist John P. Morgan examined the evidence and concluded: "There is nothing in these data to suggest that marijuana reduces people's motivation to work, their employability, or their capacity to earn wages. Studies have consistently found that marijuana users earn wages similar to or higher than nonusers."

A 1999 report from the National Academy of Sciences noted that amotivational syndrome "is not a medical diagnosis, but it has been used to describe young people who drop out of social activities and show little interest in school, work, or other goal?directed activity. When heavy marijuana use accompanies these symptoms, the drug is often cited as the cause, but there are no convincing data to demonstrate a causal relationship between marijuana smoking and these behavioral characteristics."

In his 2002 book Understanding Marijuana, Mitch Earleywine, now a professor of psychology at the State University of New York in Albany, sums up the evidence concerning amotivational syndrome this way: "No studies show the pervasive lethargy, dysphoria, and apathy that initial reports suggested should appear in all heavy users. Thus, the evidence for a cannabis-induced amotivational syndrome is weak." Recent studies finding correlations between adolescent pot smoking and academic failure or declines in IQ test scores do not change this basic picture, because they do not prove causation and do not distinguish between the impact that frequent intoxication can have on learning and the permanent neurological damage perceived by DuPont and Bennett.

Like the symptoms of cigarette use that worried Ford and Edison, the symptoms of marijuana use are often hard to distinguish from the symptoms of adolescence. Peggy Mann's 1985 book Marijuana Alert, which Nancy "Just Say No" Reagan described in the foreword as "a true story about a drug that is taking America captive," is full of anecdotes about sweet, obedient, courteous, hard-working kids transformed by marijuana into rebellious, lazy, moody, insolent, bored, apathetic, sexually promiscuous monsters. "It was very easy for parents to blame marijuana for all the problems that their children were having, rather than to accept any responsibility," observes Harvard psychiatrist Lester Grinspoon, a leading authority on marijuana. "It became a very convenient way of dealing with and understanding various kinds of problems."

The 1990 edition of Growing Up Drug Free: A Parent's Guide to Prevention, a booklet produced by the U.S. Department of Education, offered a list of warning signs: "Does your child seem withdrawn, depressed, tired, and careless about personal grooming? Has your child become hostile and uncooperative? Have your child's relationships with other family members deteriorated? Has your child dropped his old friends? Is your child no longer doing well in school—grades slipping, attendance irregular? Has your child lost interest in hobbies, sports, and other favorite activities? Have your child's eating or sleeping patterns changed? Positive answers to any of these questions can indicate alcohol or other drug use." Then again, the booklet conceded, "it is sometimes hard to know the difference between normal teenage behavior and behavior caused by drugs."

Current fears about marijuana and other illegal drugs, like fears about cigarettes at the beginning of the last century, reflect the sort of worries that reappear in every generation. Parents want their children to be smart, to do well in school, to respect authority, and to become productive, responsible adults. The dull, lazy, rebellious, and possibly criminal teenager?the cigarette fiend or pothead—is every parent's nightmare. Adults who have no children of their own worry that other people's kids will become tomorrow's parasites or predators, bringing decline and disorder.

Despite all the alarm that drug scares seem to generate, projecting these fears onto physical objects can be reassuring: Just keep the kids away from tobacco or marijuana (or alcohol or MDMA), we are implicitly told, and they will turn out OK. As symbols of all the things that might go wrong on the path from birth to maturity, drugs offer what every adult confronted by a troublesome teenager longs for: the illusion of control.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.com.