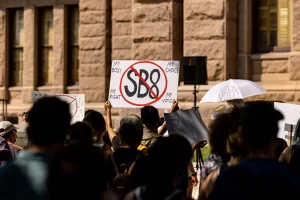

Limiting Principles and the Texas SB 8 Case - Why Texas' Law is a Greater Slippery Slope Menace than a Ruling Against it Would be

If Texas' SB 8 subterfuge works, it would be a dangerous road map for attacking other constitutional rights. The slippery slope risks on the other side are minor by comparison.

In yesterday's oral argument in Whole Woman's Health v. Jackson, a majority of Supreme Court justices seemed ready to rule against Texas and allow the lawsuit challenging SB 8 to proceed. This developments leads some commentators - including my co-blogger Stephen Sachs - to worry that the Court can't reach that conclusion in a way that has "limiting principles." If abortion providers can file preenforcement lawsuits against SB 8, despite the fact that the law delegates all enforcement to private "bounty hunters" (thereby seemingly ensuring that no state official is an appropriate defendant) are there any state laws they can't challenge in the same way?

The answer to this concern is that the slippery slope issue on the other side is far, far worse. If the Texas SB 8 subterfuge works, it will create a roadmap for undermining judicial protection for a wide range of other constitutional rights. By contrast, even if a victory for the plaintiffs opens up the door to preenforcement challenges to other laws, federal courts have lots of other ways to dispose of frivolous lawsuits, and states are, in any event, nowhere near as vulnerable as private parties threatened with violations of their constitutional rights.

Let's take each of these points in turn.

First, it is essential to recall the utter lack of limiting principles to Texas' position in the SB 8 case. As detailed in my previous writings on SB 8 (see here and here), the SB 8 strategy for evading judicial review can be used against virtually any other constitutional right, including gun rights, free speech, or freedom of religion. As Chief Justice John Roberts pointed out in yesterday's oral argument, there is also no limit to the size of the fine a state can impose on its targets. If the $10,000 or more allowed by SB 8 doesn't create enough of a chilling effect on the right targeted by the state, the latter can up the ante to $1 million or even more. These points aren't just my interpretations of Texas' position or even the Chief Justice's interpretation; Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone admitted both of them during the argument.

Steve Sachs and others argue that we need not worry too much about the above issues, because they will only be a problem in cases where courts are likely to rule against the rights-holders. If the latter are on solid legal ground, courts will swiftly vindicate them if any private plaintiff sues to try to collect the "bounty." Potential defendants therefore need not worry about ever having to pay damages, regardless of the size of the latter.

This isn't nearly as reassuring as it might seem at first glance. Many constitutional rights have fuzzy boundaries where there is room for judicial discretion in determining how far they extend. That is obviously true of abortion rights under Roe v. Wade and later Supreme Court precedent. But it's also true of gun rights, speech rights, property rights, freedom of religion, and many, many others. There are, thus, many situations where there will be at least some uncertainty about whether a court will vindicate defendants in SB 8-style bounty hunter suits. Preenforcement judicial review is the only effective way to prevent such possibilities from creating grave "chilling effects" where many people have to preemptively surrender their rights before even getting a chance to litigate them.

This danger is heightened by the reality that even a small chance of losing an SB 8-style case can have a serious chilling effect if the potential liability is large enough. Consider the Chief Justice's hypothetical example of damages of $1 million. If there is even a 5% chance that a defendant will lose, that's an expected liability of $50,000 ($1 million multiplied by 0.05), an amount large enough to deter many individuals and small businesses from exercising their rights. And if, like SB 8, the bill permits multiple lawsuits targeting the same defendant and also forces the latter to pay plaintiffs' attorneys fees if they lose, the risk can be even higher.

For these and other reasons (many of them detailed in the excellent amicus brief by the Firearms Policy Coalition), SB 8 is a potential road map for stifling judicial protection for a wide range of constitutional rights. If the Supreme Court lets Texas' subterfuge stand, it would set a very dangerous precedent.

If setting that precedent were compelled by the text or original meaning of the Constitution, perhaps we would perhaps just have to live with it. In reality, however, nothing in the text or original meaning protects state laws from preenforcement judicial review merely because the power of enforcement is delegated to private litigants. Much the contrary. As the FPC brief also explains effectively, part of the point of the Fourteenth Amendment was to give both Congress and federal courts broad power to protect constitutional rights against shenanigans by state governments. The Amendment even specifically bars states not only from enforcing laws that violate the "Privileges or Immunities" of American citizens, but also even from "mak[ing]" them in the first place. Preenforcement review is likely the only way to forestall the latter.

All that stands in the way of preenforcement lawsuits is a series of ill-conceived judicially created doctrines that give states "sovereign immunity" against many suits by individuals, and limit federal court injunctions targeting state court judges. Sovereign immunity for states against their own citizens is itself a bogus doctrine at odds with the text and original meaning. As the FPC brief points out, any sovereign immunity that does exist is also to a large extent superseded by the Fourteenth Amendment (which is the vehicle for most constitutional-rights lawsuits against state and local governments).

It is likewise an error to give state judges any special exemption from injunctions necessary to protect constitutional rights. They are bound by the federal Constitution no less than other state officials are. Indeed, fear of potentially biased state court judges was one of the reasons why the Reconstruction-era Congress enacted the Fourteenth Amendment in the first place, and sought to ensure broad access to federal courts for people threatened with state violations of their federal constitutional rights - a principle the Court recently vindicated in Knick v. Township of Scott (2019), which eliminated previous barriers to filing Takings Clause cases in federal court.

By contrast, any slippery slope effect on the other side is modest. As noted in one of my earlier posts on SB 8, federal judges have various tools for swiftly disposing of cases against state governments that lack merit. Unlike private parties threatened with liability under SB 8, state officials are unlikely to be deterred by the risk of large monetary judgments against them, because they can draw on the public fisc to pay damage awards. Neither their personal livelihood nor the future economic viability of their institutions is likely to be placed at risk.

In cases where a lawsuit challenging a state law does have merit, broader availability of preenforcement judicial review will be a feature, not a bug. It will allow constitutional rights to be protected faster, and at lower cost to potential victims. What's not to like?

Thus, there is no good reason to fear allowing preenforcement judicial review of any and all constitutional rights claims against state governments where there would otherwise be a risk of creating a "chilling effect" if claimants could only rely on "defensive" litigation.

To my mind, the best way of resolving the issue is to adopt the position advocated by the FPC, and simply sweep away anything in existing precedent that blocks lawsuits against any state officials who might otherwise have the power to enforce a potentially unconstitutional law. If this results in overbroad injunctions that cover some officials who don't have relevant authority, there is no real harm in that, as the effect will be simply to enjoin them from doing things they cannot do anyway.

But if the justices prefer to split hairs and limit any potential lawsuits to state court clerks or other "ministerial" officials whose participation is necessary to enforce SB 8, that is still better than giving free rein to Texas' subterfuge, and thereby setting a dangerous precedent. The attempt to distinguish clerks from judges strikes me as arbitrary and even silly. But if the Court is unwilling to directly limit or modify ill-advised precedents that insulate state judges from federal-court injunctions, focusing on clerks (or other lowly, but essential officials) is a reasonable strategy that is still preferable to the alternative of letting Texas' ploy work.

Ultimately, it comes down to this: The SB 8 gambit has highlighted a hole in current Supreme Court precedent, one that - it turns out - can be exploited to gut judicial protection for a wide range of constitutional rights. The Supreme Court should plug the hole. The best way to do so would be to fully sweep away the misguided precedent in question, as the FPC brief advocates. But if the Court isn't willing to go that far, a more limited (even if somewhat arbitrary) fix is preferable to the vastly more dangerous slippery slope on the other side.