6th Circuit Says Mich. Sex Offender Registry Is Punitive and, Not Incidentally, Stupid

Concluding that retroactive application of the law is unconstitutional, the appeals court also questions its rationality.

Yesterday a federal appeals court ruled that retroactive application of Michigan's Sex Offender Registration Act (SORA) violates the Constitution's ban on ex post facto laws. In doing so, the court offered a scathing assessment that suggests such laws make little sense even when they're constitutional.

Responding to a challenge brought by five men and one woman who committed sex offenses before the state legislature expanded SORA's requirements, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit concludes that the added provisions, although framed as civil regulations, are mainly punitive in their effects. That distinction between regulation and punishment is crucial because the Supreme Court has long read the Ex Post Facto Clause as applying only to the latter. In the 2003 case Smith v. Doe, the Court upheld Alaska's sex offender registry, ruling that any costs it imposed were incidental to its regulatory function. According to the Court, a law should be deemed punitive only if the legislature intended to impose punishment or if the law is "'so punitive either in purpose or effect as to negate [the State's] intention' to deem it 'civil.'" In concluding that Michigan's law goes so far beyond Alaska's that it meets the latter test, the 6th Circuit rightly questions the rationality and effectiveness of sex offender registration and the restrictions associated with it.

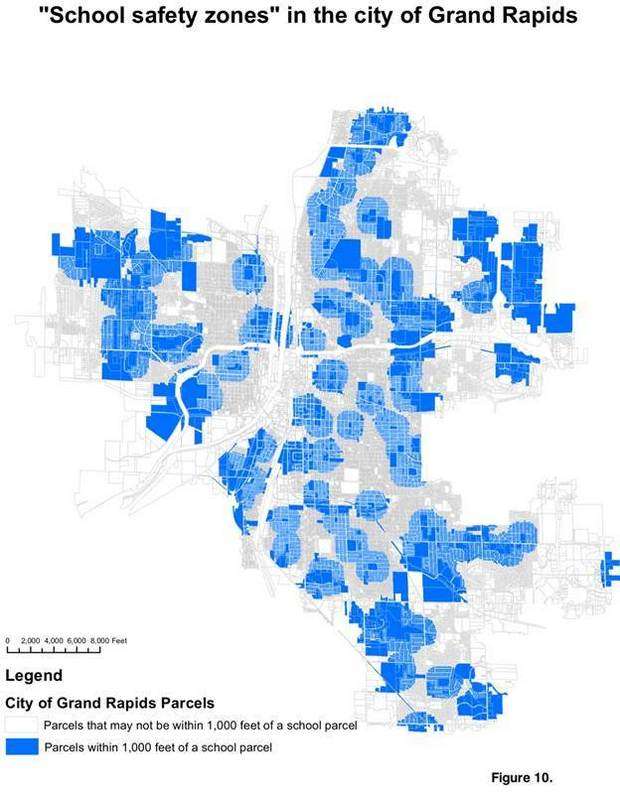

"What began in 1994 as a non-public registry maintained solely for law enforcement use…has grown into a byzantine code governing in minute detail the lives of the state's sex offenders," the court notes. Among other things, the Michigan legislature in 2006 barred registrants from living, working, or "loitering" within 1,000 feet of a school, a rule that effectively banishes sex offenders from large swaths of densely populated cities such as Grand Rapids (see map). "Sex Offenders are forced to tailor much of their lives around these school zones, and, as the record demonstrates, they often have great difficulty in finding a place where they may legally live or work," the court says. "Some jobs that require traveling from jobsite to jobsite are rendered basically unavailable since work will surely take place within a school zone at some point….These restrictions have also kept those Plaintiffs who have children (or grandchildren) from watching them participate in school plays or on school sports teams, and they have kept Plaintiffs from visiting public playgrounds with their children for fear of 'loitering.'"

In 2011 legislators compounded the registry's stigma by dividing sex offenders into three tiers that supposedly correspond to the danger they currently pose but are actually based entirely on the statutory provision they violated. That classification system, which does not include any individualized assessments, can be very misleading. All of the plaintiffs in this case qualified for Tier III, supposedly the most dangerous category. Yet one of them was convicted at age 18 of having consensual sex with his 14-year-old girlfriend, while another was convicted of "a non-sexual kidnapping offense arising out of a 1990 robbery of a McDonald's." Although neither is a rapist or child molester, they face the same requirements, including lifetime registration that will forever brand them as equally loathsome and threatening.

The 2011 amendments also included a requirement that registrants notify authorities "immediately" and in person when they move, change their names, buy or borrow a car, enroll in school, start a new job, switch to a new email address, or plan to travel for more than seven days. Failure to comply is punishable by fines and prison terms as long as 10 years.

The 6th Circuit observes that "SORA resembles, in some respects at least, the ancient punishment of banishment" as well as "traditional shaming punishments" and parole or probation. It notes that the restraints imposed by the law are "greater than those imposed by the Alaska statute by an order of magnitude" and "relate only tenuously to legitimate, non-punitive purposes."

Although SORA's restrictions are based on the assumption that sex offenders have especially high recidivism rates, the court says, there is little evidence to support that premise. Michigan presented no data on recidivism rates among the state's sex offenders (a telling omission), and research published by the Justice Department indicates that sex offenders "are actually less likely to recidivate than other sorts of criminals." Furthermore, the evidence suggests "offense-based public registration has, at best, no impact on recidivism"; in fact, laws like SORA may "actually increase the risk of recidivism, probably because they exacerbate risk factors for recidivism by making it hard for registrants to get and keep a job, find housing, and reintegrate into their communities." As for the rule excluding sex offenders from the vicinity of schools, "nothing the parties have pointed to in the record suggests that the residential restrictions have any beneficial effect on recidivism rates."

The appeals court emphasizes the mismatch between SORA's burdens and its benefits:

While the statute's efficacy is at best unclear, its negative effects are plain on the law's face….SORA puts significant restrictions on where registrants can live, work, and "loiter," but the parties point to no evidence in the record that the difficulties the statute imposes on registrants are counterbalanced by any positive effects. Indeed, Michigan has never analyzed recidivism rates despite having the data to do so. The requirement that registrants make frequent, in-person appearances before law enforcement, moreover, appears to have no relationship to public safety at all. The punitive effects of these blanket restrictions thus far exceed even a generous assessment of their salutary effects.

That harsh but justified assessment is obviously relevant not just to the constitutional question of whether retroactive application of such restrictions violates the Ex Post Facto Clause but also to the policy question of whether laws like SORA are fair or reasonable.