Are You a Woman Traveling Alone? Marriott Might Be Watching You.

How big hotel chains became arms of the surveillance state.

When a tweet accused Marriott Hotels of "working with the feds and keeping [an] eye on any women who are traveling alone," training staff to "spot an escort," and "not allowing some women [to] drink at the bar alone," Marriott's official account proudly confirmed the observation: "You are correct. Marriott employees all over the world are being trained to help spot sex trafficking at our hotels."

The brief Twitter exchange, which occurred in January, revealed some of the hidden presumptions behind Marriott's efforts to stop sexual exploitation. Not only did it suggest that the company conflates all sex work with forced or underage prostitution, but it also hinted the world's largest hotel chain considers all unaccompanied women to be worth monitoring—or, at the very least, that there's confusion about this among staff.

After many on Twitter responded that they didn't believe the policy would be non-discriminatory or effective at stopping sex trafficking, Marriott deleted the tweet without explanation. A spokesperson for the company later told Reason that the tweet was "inaccurate" and that "there is nothing in the training that advises hotel workers to look for young women traveling alone," while crediting the company's training program for removing young people from "dangerous situations." Rep. Justin Amash (R–Mich.) tweeted that his office would be looking into the incident.

But the deserved dustup points to a much bigger issue than unusually watchful hotel staff. It's part of a Homeland Security-backed coalition using human-trafficking myths and War on Terror tactics to encourage citizen spying and the development of new digital surveillance tools.

However well-intentioned, the surveillance tactics that have been adopted by hotel chains are part of a disturbing partnership between hospitality businesses, federal law enforcement, and rent-seeking nonprofits that increasingly seeks to track the movements and whereabouts of people, especially women, all over the country. Under pressure from the federal government and driven by persistent myths about the nature and prevalence of sex trafficking, hotel chains like Marriott have become the new frontiers of the surveillance state. Like the indiscriminate spying campaigns that grew out of the 9/11 attacks, it's an effort based on panic, profiling, and stereotypes, and it is nearly certain to ensnare more innocents than it helps.

Carceral Hospitality

For years, the federal government has funded partnerships with hotels, airlines, truckers, and other public-facing industries under the mantle of stopping human trafficking and sexual exploitation. In theory, this partnership puts the private sector on the frontlines of rooting out abuse.

In practice, however, these efforts have largely wound up as law-enforcement-driven attacks on sex workers and their clients, on immigrants, and on other members of marginalized communities. Along the way, victims of actual trafficking are often swept up in the arrests and incarceration.

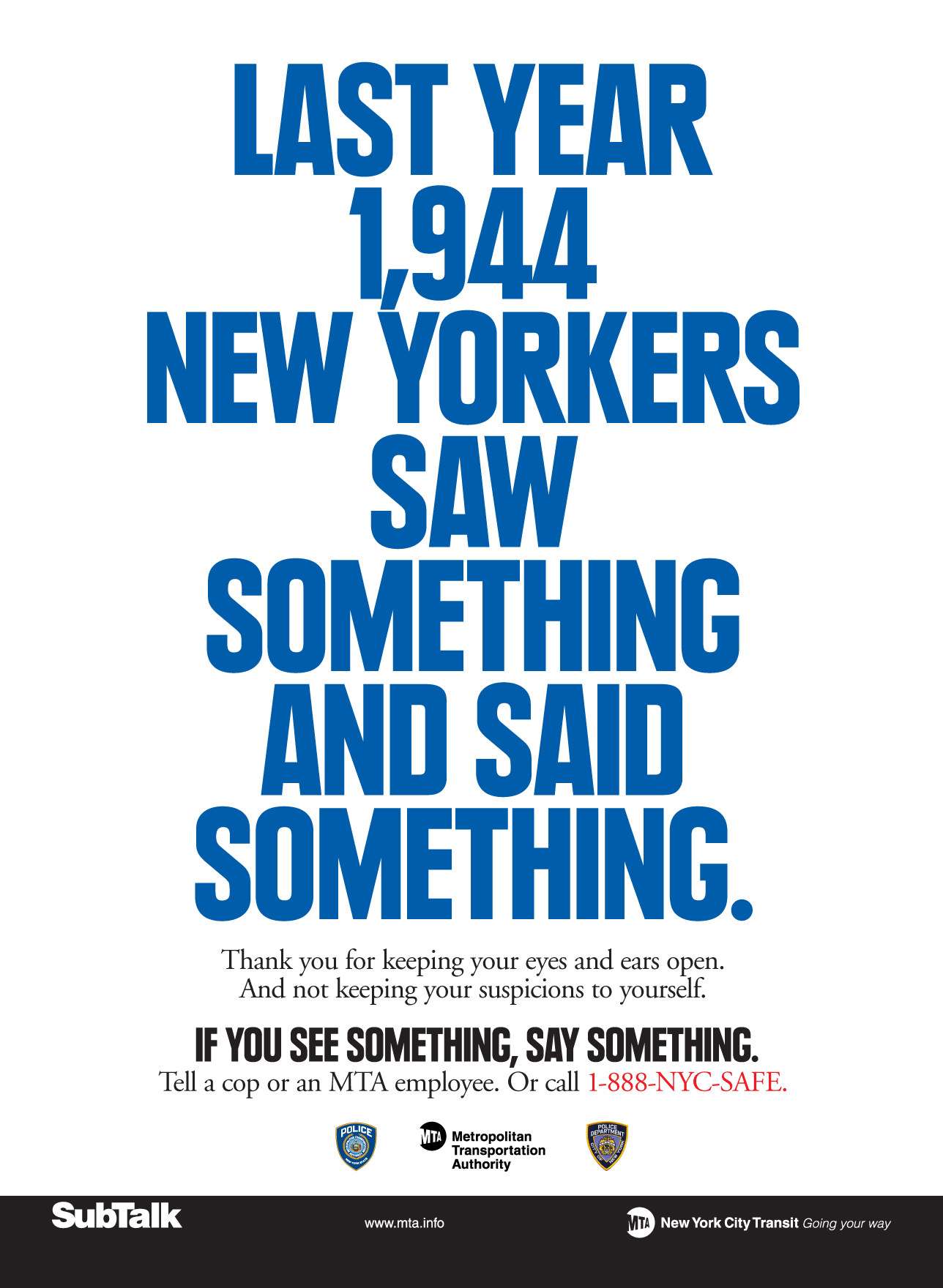

Many of these efforts fall under the purview of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) "Blue Campaign," which has been in place since 2010. Promoted as a way to help hotel and transit staff, hospitality businesses, and travelers "recognize the signs" of human trafficking, the Blue Campaign is best understood as an update to the war-on-terror surveillance systems developed under the George W. Bush administration. It relies on tactics adapted from "If You See Something, Say Something," or S4, a campaign run by DHS that stems from New York City's turn-of-last-century subway slogans.

The Big Apple's push to enlist ordinary citizens in watching out for terrorists was an iconic part of post-9/11 security theater, and it remains a symbolic reminder of the ways that widespread panic about terrorism drove what were effectively campaigns of broad-based racial and ethnic profiling.

In 2010, DHS bought and relaunched the S4 program as part of the Nationwide Suspicious Activity Reporting Initiative at the Department of Justice (DOJ).

Working under this framework, the Blue Campaign seeks "to gather lead-generating intelligence through training sector specific industries," writes U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Brandon R. Winters in "The Hotel Industry's Role in Combating Sex Trafficking," his postgraduate thesis for the Navy-run Center for Homeland Defense and Security. The campaign "essentially leverages the U.S. populace to act as [human intelligence] collection sources for suspicious activities throughout the country."

Marriott International and many other hotel chains have adopted Blue Campaign tactics. In 2017, Marriott made "anti-trafficking" training mandatory for all 750,000 of its employees worldwide. CEO Arne Sorenson described it as "educating and empowering our global workforce to say something if they see something."

Marriott is also a part of Homeland Security's Critical Infrastructure Cross Sector Council, which was formed in 2015 to govern "the private sector's cooperative efforts to advance" DHS priorities. In a 2016 update, Council Chairman Tom Farmer said that "the public has increased its reporting of suspicious activity" thanks to their efforts but "needs additional education on what types of activities should be reported, to whom they should be reported, and how reporting them makes a difference."

The Blue Campaign's spot-a-trafficker tips include looking for people who appear fatigued or sleep deprived, guests not wanting cleaning staff in their room, a woman "waiting at a table or bar and picked up by a male," a car parked with its license plate away from the door, a guest with multiple computers or phones, booking multiple rooms under one name, having a lot of condoms or "sex paraphernalia" around, too many men entering one room, and any "unusual behavior."

It's exactly the kind of vague invitation for snooping and snitching that will inevitably snare sexual activity between consenting adults, from sex workers and their customers to couples who don't sit right with staff. In several recent high-profile cases, airline staff trained to "spot traffickers" have harassed interracial couples and families. When people are asked to use gut instinct to stop real but rare horrors, relying on racial stereotypes and other biases tends to rule.

Blue Campaign imperatives also invite harassment of people doing nothing sexual at all. Who hasn't exhibited fatigue or sleep deprivation while traveling? Or backed into a parking spot for reasons other than evading detection?

Dads staying at hotels with teenage or young-adult daughters should probably beware, too.

And we can certainly expect some sexism in calculations. Women in male-dominated industries who drink at the bar with male colleagues may also face embarrassing attention from hotel staff. Women not dressed modestly enough for someone's liking will be pegged as potential victims. Female hair stylists, make-up artists, or personal trainers who book appointments in hotels are also likely to be targeted.

Much anti-trafficking rhetoric encourages focusing on class markers, listing shabby clothes or differences in dress compared to companions as warning signs. In general, any misunderstandings are likely to fall hardest on stereotyped subgroups—people of color, gay couples, transgender or gender non-conforming people, immigrants.

Maybe that's the point. The Blue Campaign directs anyone who spots suspicious activity to call the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) tipline or visit www.ice.gov/tips.

Crony Charities, Bad Laws

In June 2016, Connecticut enacted a law requiring hospitality staff in the state to get human trafficking training. In 2018, New York legislators considered something similar. These laws are one of the latest trendy lobbying efforts from awareness charities that get lots of government and corporate grant money to tell governments and corporations how to "help."

Hotels are now inundated with government messaging about keeping closer tabs on customers. Employees "are often in the best position to see potential signs of trafficking," says the Blue Campaign hospitality toolkit.

But these messages do not direct onlookers to contact local police about potential crimes. They say to call 911 in an emergency and otherwise report suspicions to ICE or to call a "National Human Trafficking Hotline" run by the Polaris Project, a nonprofit focused on trafficking issues that works closely with the FBI.

Both Polaris Project and ECPAT-USA—another nonprofit well-connected with federal authorities—helped develop the Marriott International training module, which can now be purchased from the American Hotel and Lodging Association and which was made free for hospitality companies in Connecticut. ECPAT-USA, which bills itself as the nation's leading policy organization working to "end the commercial, sexual exploitation of children," is now pushing laws that would require hotel staff to receive anti-trafficking training of the sort they design and make money from. (Neither ECPAT-USA nor Polaris Project responded to inquiries.)

In a review of Marriott anti-trafficking training clips, Business Insurance reported that housekeepers were asked to note if someone "has little or no luggage" or there is "evidence of pornography," and "restaurant workers are told to watch for victims who are 'dressed inappropriately' or are 'seen with many older men.'"

According to the group's 2017 annual report, "six out of the 10 largest hotel chains in the world partner with ECPAT-USA." The report also calls 2017 "a banner year for advocacy" since, "after a decade-long fight," there was finally support in Congress for The Stop Online Sex Trafficking Act, or SESTA, and the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, or FOSTA. (The bills would be rolled into one and signed into law last March, much to the harm of sex workers, trafficking victims, tech companies, and free speech everywhere.) ECPAT-USA touts its status as "one of a select group of advocacy organizations" who worked directly on the legislation and credits its history of bridging the private and government sectors for bolstering efforts to pass the law.

With FOSTA on the books, ECPAT-USA has turned its attention to legislation targeting the hospitality industry.

In a "best practices" guide for hotel managers, ECPAT-USA says they should require photo ID and vehicle information from guests upon check-in; "verify that all guests and visitors who enter are captured and recorded" on security footage; "monitor online sex ads…for your hotel name and pictures of your rooms and guests"; block access "to popular websites for online sex ads"; only keep one door to the building open at night; require that all visitors to hotel guests stop at the front desk, show identification, and be met by a guest in the lobby; and refuse to accept cash. It asks hotel staff to increase surveillance of all guests, "be wary of requests for rooms close to exits," watch for too many visitors to the same room, report rooms with "excess condoms, lubricants, sex toys, lingerie," and be suspicious of guests wearing oversized hats or sunglasses.

Risky Women

Hotels are reacting partly to legal pressure. Chains have recently been hit with a spate of lawsuits seeking to hold them accountable for any prostitution on the premises. "There are advocacy groups that are really pushing this issue, saying here are lists of red flags," Philadelphia attorney Charles Spitz told Business Insurance in 2017. "If you knew these red flags were raised, it will be hard to argue that you did not know."

Cook County, Illinois, Sheriff Tom Dart, who previously mounted aggressive national campaigns against Craigslist and Backpage over prostitution ads posted to those sites, has started focusing his energy on eradicating sex work at hotels. "You name a hotel and I guarantee we've made an arrest or we could," Dart told Business Insurance. He also praised Marriott's training videos and efforts.

"While civil liability for hotels is garnering the most attention, criminal liability…and reputational risk are other soft spots for the industry that could be facing an onslaught," warned Business Insurance. It noted that insurance firms were starting to discuss human-trafficking liability plans with hotel clients.

All of this adds up to a climate of inflated suspicion at hotels, where staff are being told to imagine that sex slavers lurk behind every pair of big sunglasses and asked to view all single ladies as potential sex workers.

Neither hotels nor government agents have provided details on the efficacy or wisdom of these see-something, say-something policies, but if the results from similar programs, implemented as part of the war on terror, are any guide, the success rates are probably dismal. The New York City Metropolitan Transit Authority bragged that it had received 1,944 tips in 2007 from its "see something, say something" campaign. According to The New York Times, those tips produced no arrests. More recently, the TSA's "Quiet Skies" program—in which plainclothes U.S. Marshals were enlisted to spy on airport travelers, with no results—showed that not even agents specially trained officials are very good at the sort of thing hotel staff are being asked to do.

But from a business standpoint, results are probably beside the point. This is about reducing legal liability, pleasing the feds, and racking up points for "corporate social responsibility."

Crowdsourced Surveillance

While Homeland Security rebrands citizen-spying efforts as a campaign to stop sex trafficking, various agencies are working behind the scenes on similar projects. Using social media, machine learning, hotel photos, online ads, and artificial intelligence, these groups—including the Department of Defense's research arm and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)—are building powerful tools that can have dangerous uses far beyond policing prostitution.

One such tool is TraffickCam, an app that anyone can use to upload detailed photos of their hotel rooms. The project "allows these photos to be directly downloaded to the FBI server to help law enforcement identify victims, survivors, missing persons, and probable johns or pimps," explains the Southwest Michigan Anti-Trafficking Task Force.

As of April 2017, TraffickCam contained 2 million publicly available images and 126,000 photos uploaded by hotel guests, the company said.

Sex-worker ads featuring photos in hotel rooms can be entered into the database to reveal which hotel the picture was taken in. Which of course also means that any photo of anyone in a hotel room can be entered in the database to determine where he or she was. It is hard to imagine that this technology won't be abused.

Last year, the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) awarded more than $1 million to George Washington University to develop "an enhanced version of the TraffickCam system" that can pinpoint hotel locations based on very small details. Another NIJ-funded project from 2018 is using "machine learning and social network analysis" to build "a significant new capability for law enforcement": After collecting and archiving data "from online review websites," the goal is to develop a system that is "optimized to detect and classify online reviews," with escort ads serving as a test case.

Escort Reviews, Hotel Pics, and Gun Ads

TraffickCam and many related projects are part of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Administration (DARPA) Memex program. More than 100 million documents are now in the Memex database, including a huge archive of content from Craigslist, Backpage, and other classified-ad, escort review, and social media platforms.

Some 80 million web pages and 40 million images have been indexed.

The majority of the archives consist of sex-related content—information indexed from adult ads include everything from the number of first-person pronouns used to "cup size" and chest measurement, along with location, contact, and demographic data pulled from individual ads. Photos, videos, and page metadata were also saved.

A significant portion of the Memex cache also comes from arms sale and review sites—largely Armslist.com, but more than 80 sites and forums in total. The Memex database holds 7.2 million images and files related to gun sales. The government probably knows if you've ever advertised sex work or a gun for sale between 2014 and 2017. And it has receipts.

It's also been freely sharing them with a huge array of public, private, and law enforcement partners. "All in all," said DARPA program manager Wade Shen in a January 2017 DOD news release, "we have hundreds of people who are working on this effort."

Memex had 17 different main partners, many of whom also had partners of their own. Through them, DARPA's trove of sex work ads, independent gun sales, hotel photos, and other Memex-derived content has been used in a huge array of research, including efforts to improve automated facial recognition.

Much of it has some serious ethnic profiling built into its parameters. One study trying to suss out indicators of "trafficking, rather than voluntary escort activity," lists "ethnicity-related clues" as a good way to find brothels "fronting as" massage parlors. (It calls its efforts "AI for social good.") Another says signs of likely sex trafficking included references to spas or massage, body weights below 115 pounds, and posters from Southeast Asian countries.

Though the efforts are couched in anti-trafficking terms, the federal government is actually developing knowledge and tools that can very efficiently surveil, archive, and interpret all sorts of digital content and metadata.

One Memex-funded program alone, called DIG, can index 5,000 web pages per hour and turn the content into a searchable database. "To get enough training data, DIG uses [the crowdsourcing marketplace] Amazon Mechanical Turk to recruit people to read escort ads and highlight key information like eye color, hair color, and the working name of people featured in escort ads," reported PBS. As of 2017, it was being used by more than 200 law enforcement agencies.

DOD's $67 Million Cache of Escort Ads

Between 2014 and 2017, DARPA spent $67 million on the adult-ad indexing program. Is it worth it?

Certainly not from an anti-trafficking standpoint. A 2018 paper from NASA JPL researchers said that in the past year, "DIG, along with other trafficking detection tools from Memex, has led to at least three trafficking prosecutions."

Three.

The results are indicative of the flawed focus of so-called anti-trafficking campaigns. How many victimized people could have been helped with $67 million going to emergency shelters and other services that address material needs?

Instead, the federal government is paying the nation's top scientific minds to pretend it's possible to build an algorithm for sniffing out evildoers if we can just input the right code words, images, emojis, and clues. Those minds then work on things like figuring out how to use bots to scrape content from password-protected websites and forums, building up "the ability to rapidly and automatically monitor [online] gun transactions" and use "object recognition and computer vision" to tell if guns are automatic or semi-automatic, or creating "an approach to identify users across website forums using indirect features derived from metadata on each of the websites."

In other words, the tools developed using escort ads aren't going to stay in the realm of saving trafficking victims or even uncovering consensual but illegal advertisements for sex.

Meanwhile, DHS is deputizing private sector snitches. Hotels, airlines, and others are subjecting staff to training sessions that are pointless at best, destructive at worst. And nobody is worrying about the conditions facing hospitality staff employees, who have historically faced high levels of labor trafficking and sexual abuse themselves. At the same time, this approach makes hotels less amenable to guests, especially single women, by treating them with unwarranted suspicion.

As Marriott gets kudos for "donating" its training course to other hotels, and as ECPAT and its allies push for laws mandating a wasteful corporate branding exercise in even more states, remember: Hiding within this goodwill-garnering campaign are a straight-to-ICE pipeline, crackdowns on consenting adults, the creation of advanced new spying tools, and nonprofit cronyism, all of which inevitably comes at the expense of activities that could actually benefit sex-crime victims. This isn't a recipe for good hospitality or good work against exploitation and abuse.

*CORRECTION: This piece initially stated incorrectly that the Department of Homeland Security is a part of the Department of Justice. It is a separate cabinet agency.