Why I'm Teaching My Son To Break the Law

Making the world freer is always right, especially when the law is wrong

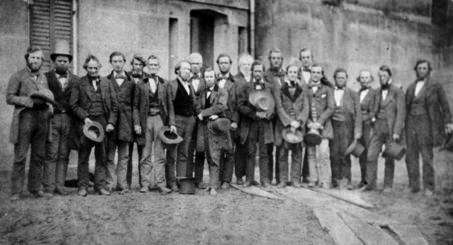

In 1858, hundreds of residents of Oberlin and Wellington, Ohio—many of them students and faculty at Oberlin College—surrounded Wadsworth's Hotel, in Wellington, in which law enforcement officers and slavehunters held a fugitive slave named John Price, under the authority of the Fugitive Slave Act. After a brief standoff, the armed crowd stormed the hotel and overpowered the captors. Price was freed and transported to safety in Canada (that's a photo of some of the rescuers in the courtyard of the Cuyahoga County Jail, below and to the right). I know these details because my son recently borrowed from the library The Price of Freedom, a book about the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, as the incident is called (PDF). My wife and I used it as a starting point for telling our seven-year-old why we don't expect him to obey the law—that laws and the governments that pass them are often evil. We expect him, instead, to stand up for his rights and those of others, and to do good, even if that means breaking the law.

Our insistence on putting right before the law isn't a new position. I've always liked Ralph Waldo Emerson's sentiment that "Good men must not obey the laws too well." That's a well-known quote, but it comes from a longer essay in which he wrote:

Republics abound in young civilians, who believe that the laws make the city, that grave modifications of the policy and modes of living, and employments of the population, that commerce, education, and religion, may be voted in or out; and that any measure, though it were absurd, may be imposed on a people, if only you can get sufficient voices to make it a law. But the wise know that foolish legislation is a rope of sand, which perishes in the twisting …

Rope of sand the law may be, but it can strangle unlucky people on the receiving end long before it perishes. John Price could well have ended up with not just the law, but a real rope, around his neck, just because he wanted to exercise the natural freedom to which he was entitled by birth as a sapient being.

John Price ended his life as a free man because he was willing to defy laws that said he was nothing but the property of other people, to be disposed of as they wished. He got a nice helping hand in maintaining his freedom from other people who were willing to not only defy laws that would compel them to collaborate in Price's bondage, but to beat the hell out of government agents charged with enforcing those laws.

Emerson would likely have approved. His son reported years later that, upon learning that his children were writing school compositions about building houses, he told them, "you must be sure to say that no house nowadays is perfect without having a nook where a fugitive slave can be safely hidden away."

Much influenced by Emerson, but more down to Earth, Henry David Thoreau went to jail (however briefly) for refusing to pay tax to support the Mexican War. In an essay now known as "Civil Disobedience," he wrote:

Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator? Why has every man a conscience then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right.

This is the same essay in which Thoreau famously stated, "that government is best which governs not at all." Government was not an institution he held in high regard. He fretted that soldiers, police, and other officials "serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines" and that "in most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgment or of the moral sense; but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones."

Ours being a more academic and less poetic age, Thoreau's sentiments are likely to be captured these days as embodying the divide between Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development. Specifically, they mark the difference between conventional thinkers who believe the law is due obedience because somehow it defines morality, and post-conventional thinkers who believe that higher principles take precedence over the law.

Yeah, I prefer Emerson and Thoreau, too.

Personally, I would say that I love liberty more than any other value, and I don't give a damn if my neighbors or the state disagree. I will be free, and I'm willing to help others be free, if they want my assistance. Screw any laws to the contrary. I don't think social psychologist Jonathan Haidt would be surprised at my attitude. According to him, that's what makes libertarians tick. And that's what my wife and I are trying to pass on to our son.

Slavery and the Mexican War are, thankfully, dead issues in this country, but that doesn't mean there's any shortage of objectionable restrictions and mandates laid upon us by law and the government. Taxes, nanny-state restrictions, business regulations, drug laws … All beg for defiance. The Fugitive Slave Law may no longer command Americans to do evil, but "safety" rules would have physicians and mental health professionals snitch on their patients. And there's always another military adventure, someplace, on which politicians want to expend other people's blood and money.

I sincerely hope that my son never has to run for his freedom in defiance of evil laws, like John Price. I also hope, at least a little, that he never has to beat the stuffing out of police officers, as did the residents of Oberlin and Wellington, to defend the freedom of another. But, if he does, I want him to do so without reservations.

If all my son does is live his life a little freer than the law allows, then we've done some good. A few regulations ignored and some paperwork tossed in the garbage can make the world a much easier place in which to live. Better yet, if he sits on a jury or two and stubbornly refuses to find any reason why he should convict some poor mark who was hauled in for owning a forbidden firearm or for ingesting the wrong chemicals. Jury nullification isn't illegal (yet), but it helps others escape punishment for doing things that are, but ought not be. No harm, no foul is a good rule for a juror, no matter what lawmakers say.

And, if he wants to go beyond that, and actively help people defy the prohibitions and authoritarian outrages of the years to come, he'll be cheered on by me, his mother, and perhaps even (depending on your views on the matter) an approving audience of spectral ancestors. Our family has long experience with scoffing at the law. Purveying the forbidden or conveying the persecuted are honorable occupations, whether done for profit or out of personal commitment.

As I think our son has already come to appreciate, making the world freer is always right, especially when the law is wrong.