The Forgotten Classical Liberal Who Fought Jim Crow and Championed Immigration

Remembering the legacy of a principled legal activist.

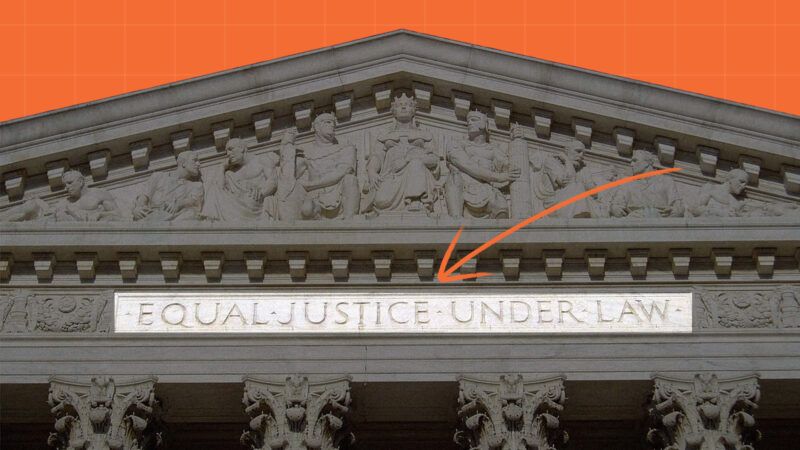

In the early months of 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court decided two cases that might not initially appear to share anything in common.

In Tyson and Brother v. Banton, the Supreme Court struck down a New York law forbidding the resale of theater tickets "at a price in excess of fifty cents in advance of the price printed on the face of such ticket." "If it be within the legitimate authority of government to fix maximum charges for admission to theaters," observed the Court, "it is hard to see where the limit of power in respect to price-fixing is to be drawn."

Then, a week later, in Nixon v. Herndon, the Supreme Court struck down a Texas law forbidding African Americans from voting in the state's Democratic primary elections. "It is too clear for extended argument," the Court declared, "that color cannot be made the basis of a statutory classification affecting the right set up in this case."

So, can you guess the connection between the two cases?

You’re reading Injustice System from Damon Root and Reason. Get more of Damon’s commentary on constitutional law and American history.

You may be forgiven if the name Louis Marshall did not immediately spring to mind. A mostly forgotten figure today, Marshall (1856–1929) was a prominent lawyer and activist who argued and won a series of significant legal victories during the Progressive Era, including the two SCOTUS cases described above.

Marshall was a leading reformer during the Progressive Era, but he was no Progressive. Rather, he was a classical liberal. He championed property rights and economic liberty in regulatory cases while championing the rights of racial, ethnic, and religious minorities in civil rights cases.

That's the link between the New York price-fixing case and the Texas all-white primaries case. Marshall's distinctively individualist fingerprints are to be found all over both of them.

"There must be a limit to the so-called police power," Marshall wrote in a 1923 letter, referring to the regulatory power of state officials. "What right has the Legislature to say to me how much or how little I may receive for that which belongs to me—my labor." In other words, Marshall subscribed to the school of constitutional thought represented by the Supreme Court's 1905 decision in Lochner v. New York, which struck down an economic regulation for violating the individual right to liberty of contract.

"You will be interested to know that the Supreme Court of the United States yesterday handed down its decision in Nixon v. Herndon," Marshall wrote to another correspondent a few years later. The decision "was unanimous," he noted with pride, and it "followed my brief very closely." He added: "The decision is regarded as a most important pronouncement and will have a wide-reaching effect." Marshall was right about that. Nixon v. Herndon would stand at the foundation of a line of cases that ultimately destroyed the racist system of all-white primary elections.

Marshall also played an important role in the early success of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1917, Marshall was part of the winning legal team behind Buchanan v. Warley, in which the Supreme Court struck down a Jim Crow residential segregation law for violating the property rights of black and white Americans. Marshall's fellow classical liberal, the great libertarian lawyer Moorfield Storey, spearheaded that case in his official capacity as president of the NAACP.

The same principles of liberty and equality also guided Marshall's stance on immigration. "This is a country of immigrants," he once declared. "I say that it is not true Americanism and it is not right or just that we shall bar the doors of opportunity against" those immigrants then arriving on U.S. shores.

The child of German-Jewish immigrants himself, Marshall was especially outraged by the rising anti-immigrant sentiments of the Progressive period. Testifying before Congress in 1924, for example, he denounced as both anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic the soon-to-be-passed National Origins Quota Act, which severely restricted all immigration from southern and eastern Europe.

"One would say, having recently read the proclamation of the Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan," Marshall testified, "that the ideas which underlie its theory of Government in the United States find an echo in this legislation, because the people who are to be admitted are white, largely Protestant, and are of so-called Anglo-Saxon stock, while those who are to be excluded are not Protestants and are not Anglo-Saxon, although they are white." Despite the concerted opposition of Marshall and others, however, that odious measure cleared Congress and was signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge.

As a true believer in the fundamentals of classical liberalism, Louis Marshall fought with equal fervor on behalf of economic liberty, civil rights, and the rights of immigrants. His principled impact on American law deserves to be better remembered today.