Hotel Sex Trafficking Suit Can Proceed, Inviting Hotels to Profile and Harass Guests

Can a hotel be guilty of sex trafficking just because it didn't surveil its customers enough?

A hotel could be legally liable for sex trafficking because it failed to intervene against a guest who wore "sexually explicit clothing" and had condoms in her room, according to a recent ruling from Judge Matthew J. Kacsmaryk of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas.

Kacsmaryk—who gained national notoriety a few years ago for a ruling that suspended approval of the abortion pill mifepristone—denied the hotel's motion to dismiss a civil suit that accused it of knowingly benefiting from participation in a sex trafficking venture.

You are reading Sex & Tech, from Elizabeth Nolan Brown. Get more of Elizabeth's sex, tech, bodily autonomy, law, and online culture coverage.

The lawsuit was brought by "J.H." against Paramount Hospitality, a company that manages hotels. J.H. alleges that she was trafficked for sex at a hotel owned and operated by Paramount Hospitality.

Paramount Hospitality filed motion to dismiss the suit. In an August 1 ruling, Kacsmaryk denied the hotel management company's motion to dismiss.

The case raises a lot of alarms—and not about Paramount Hospitality.

Part of a Dangerous Trend

The suit turns on whether the hotel company violated the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008. That act amended the main federal anti-trafficking statute to allow sex trafficking victims—that is, people forced, coerced, or defrauded into sex for money—to not only sue their traffickers in civil court but also sue any entity that "knowingly benefits" or "attempts or conspires to benefit" from "participation in a venture" engaged in sex trafficking.

The change may have been predicated on the common misconception that sex trafficking is frequently the work of higher profitable and organized trafficking "rings," instead of one or two low-level criminals victimizing those around them. The language would thus allow victims to go after these deep-pocketed rings instead of merely against a direct perpetrator.

Since the law changed, we've seen all sorts of attempts to stretch what it means to "knowingly benefit" from a "sex trafficking venture." People have gone after classified ad websites, social media platforms, and hotels.

In a sane judicial system, sex traffickers would be the main entity held liable for sex trafficking—not any old place where sex traffickers happen to be or advertise. But for reasons both political and financial, we've seen growing attempts to hold third parties legally liable for allegedly facilitating prostitution, whether it involves consenting adult sex workers or actual trafficking victims.

The result is a lot of lawsuits against entities that have very dubious ties to trafficking—and a growing push for surveillance, online and off, that seems to come down hardest on already marginalized groups and people.

"Sexually Explicit Clothing" and "Drug Paraphernalia"

The problem posed by cases like these is the knowing aspect. Sure, hotels may take money from people renting rooms, thereby "benefiting" from crime if their customers happen to be sex traffickers. But it's very hard to prove—and hard to imagine—that these companies intended to be in league with sex traffickers.

And indeed, most such cases present no evidence that hotel management or staff overtly did so. Rather, they rely on the idea that the hotels willfully ignored the "signs" of sex trafficking.

In this case, J.H. says the hotel should have known she was being trafficked because there was "suspicious foot traffic" to her room and sometimes "loud noise" coming from it, because she wore "sexually explicit clothing," because she was "impaired" on meth and had "visible bruising," and because there were things such as "drug paraphernalia," a gun, and "condoms" in her room.

That is, perhaps, a lot of suspicious elements—if you're some sort of omniscient hotel ruler who sees all and knows all. But it seems unlikely that any one staffer encountered all of these signs, or that workers who saw one thing would have felt compelled to talk about it with other staff members.

Surely, hotel maids come across condoms and drug paraphernalia all the time and aren't running to hotel management every time they do. Anyone in a position to hear "loud noises" from J.H.'s room, or see "foot traffic" from it, wouldn't necessarily be in a position to see her at all, let alone up close enough to see any bruises. Likewise, someone who saw a scantily clad woman walking around like she was drunk or on drugs wouldn't necessarily know what was in her room, or who was coming and going from it.

How Would This Work?

The implication from suits like these is that hotel staff need to regard all customers with suspicion and be way more up in everyone's business. That they should call the cops if they see a woman who appears intoxicated or has men coming into her room, or perhaps refuse to do business with a woman dressed too immodestly.

Can you imagine how this would play out in practice?

It would certainly require hotels to reject (or call the cops on) anyone engaged in sex work, including legal sex work done entirely consensually.

But it goes beyond that, of course. Asking hotel staff to recognize and act on vague "signs" of sex trafficking means asking them to intervene in all sorts of cases that will be nothing of the sort.

It means asking them to harass women for traveling alone while being aloof or wearing a short skit. It means asking them to harass lovers meeting up for a hotel room tryst. It practice, it very likely means staff harassing interracial couples or multi-racial families, as we have seen with airline staff who were "trained" to "spot trafficking."

When hotel owners face huge lawsuits and fines for failing to profile people, you're going to end up with a lot of innocent people being harassed.

No Way Out for the Accused

The biggest problem with cases like these is what they mean for surveillance and profiling broadly. But it's also worth mentioning how hard cases like this are to defend.

In this case, the alleged trafficking took place in almost a decade before the suit was filed, in 2015 and 2016. J.H. did not identify her alleged trafficker in her complaint against Paramount, and the court declined to make her do so. "The identity of Plaintiff's traffickers is of no import in the instant case," Kacsmaryk wrote.

Defending against such a suit seems, on its face, nearly impossible. Since there is no named trafficker, the company can't even check whether such an individual even stayed at their hotels, let alone attempt to ascertain any facts that would allow for a defense in this case.

Perhaps this will become an issue later—there has not yet been a ruling on merits of the suit yet. But by denying Paramount Hospitality's motion to dismiss, Kacsmaryk is at least signaling that similar cases can have some legs, and companies will have to expend significant time and resources defending against even the flimsiest or most vague of allegations.

Followup: Britain's Online Safety Act Comes for Reddit

"On July 25, users in the UK were shocked and rightfully revolted to discover that their favorite Reddit communities were now locked behind age verification walls," the Electronic Frontier Foundation points out:

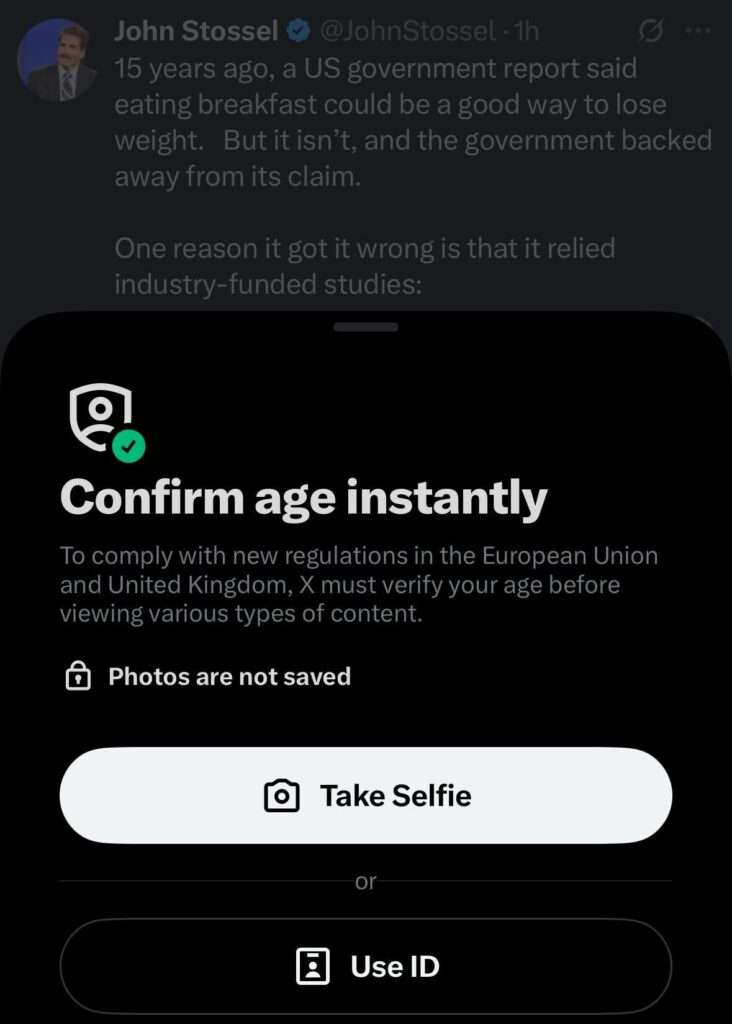

Under the new policies, UK Redditors were asked to submit a photo of their government ID and/or a live selfie to Persona, the for-profit vendor that Reddit contracts with to provide age verification services.

For many, this was the first time they realized what the [Online Safety Act] would actually mean in practice—and the outrage was immediate. As soon as the policy took effect, reports emerged from users that subreddits dedicated to LGBTQ+ identity and support, global journalism and conflict reporting, and even public health-related forums like r/periods, r/stopsmoking, and r/sexualassault were walled off to unverified users. A few more absurd examples of the communities that were blocked off, according to users, include: r/poker, r/vexillology (the study of flags), r/worldwar2, r/earwax, r/popping (the home of grossly satisfying pimple-popping content), and r/rickroll (yup). This is, again, exactly what digital rights advocates warned about.

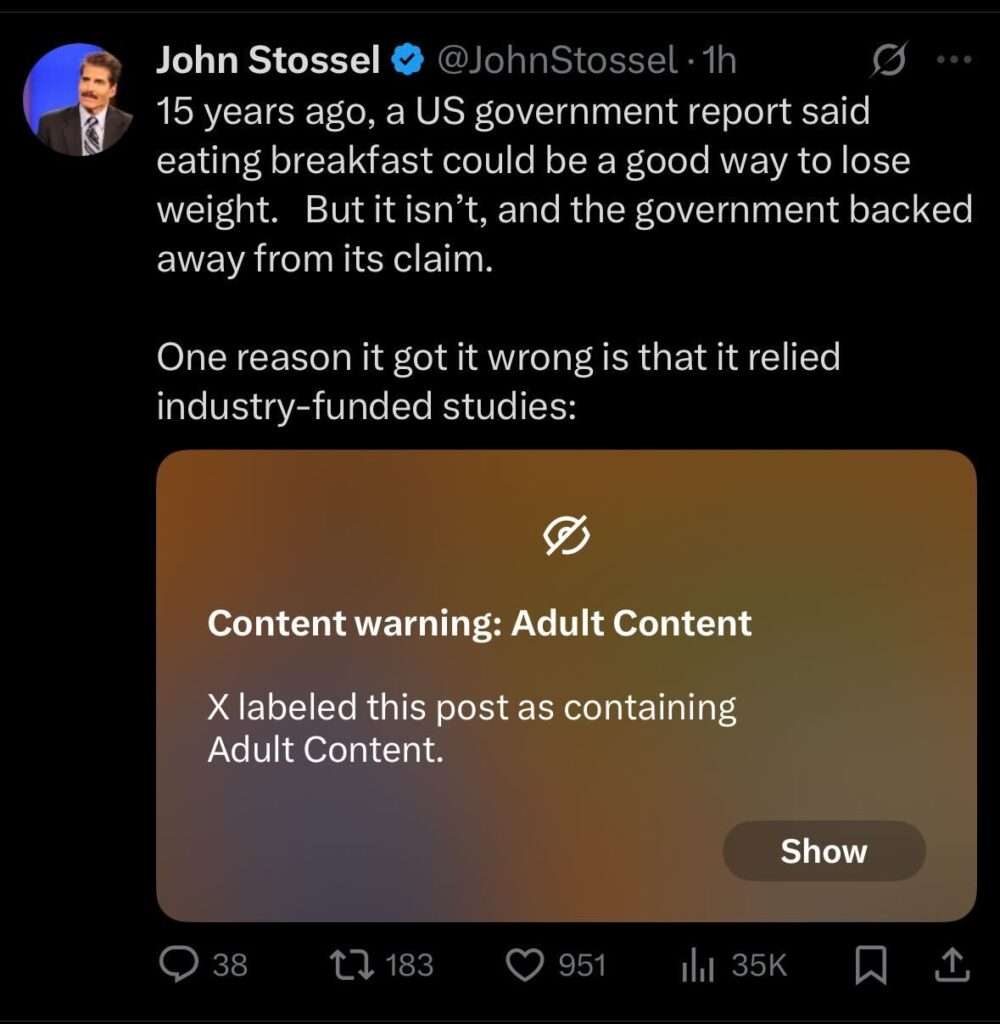

In related news, Reason's Jack Nicastro, visiting France, was asked to show age to view a Stossel tweet:

For more on the fallout from this measure, see last Wednesday's newsletter.

More Sex & Tech News

• In Germany, "the state media authorities want to force financial service providers to refuse payments to erotic portals such as Pornhub and Youporn—including payments from adults," according to Heise News. "The legal basis for this is the new Interstate Treaty on the Protection of Minors in the Media."

• Florida is purging young adult books that have sexual themes. "Broward school administrators have given schools a list of 55 books that must be removed, the latest move in a statewide effort to ban certain materials from school libraries," the South Florida Sun Sentinel reports:

The list includes titles that have been frequently challenged in Florida and around the country, including: "Forever…" by Judy Blume, "Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West" by Gregory Maguire, "This Book Is Gay," by Juno Dawson, and "All Boys Aren't Blue" by George M. Johnson.

The district said the removals are by order of the state Board of Education. Other school districts in the state are removing these same books.

• Australia will include YouTube in its ban on social media for anyone under the age of 16.

• "In a small clinical trial, the first hormone-free birth control for males—a pill that stops sperm production—was deemed safe for human use and approved for further clinical trials, after being found effective in animal studies," writes Naomi Darom at The Gender Nerd, in a post that explores whether men are likely to take a male birth control pill.

• Can AI reason by analogy, like human beings do?

Today's Image