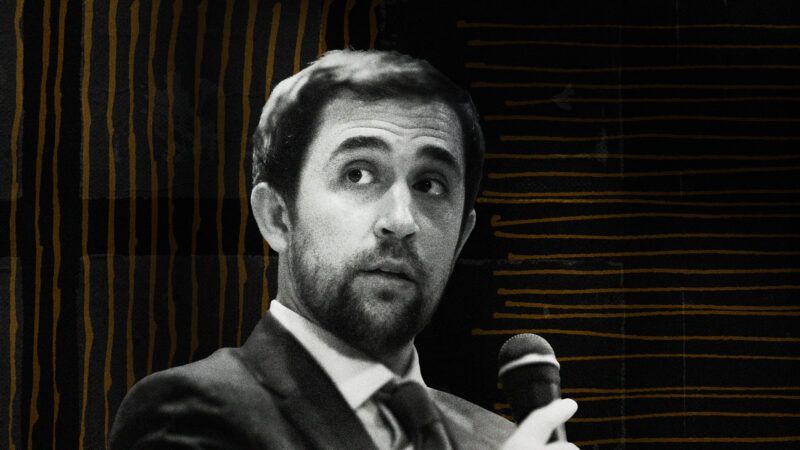

Christopher Rufo Wants To Shut Down 'Activist' Academic Departments. Here's Why He's Wrong.

"Professors are not mouthpieces for the government," says FIRE's Joe Cohn. "For decades, the Supreme Court of the United States has defended professors' academic freedom from governmental intrusion."

In an essay published this week in City Journal, conservative activist Christopher Rufo argued that universities—or rather, the state legislatures governing these universities—should shut down "activist" academic departments. But rather than protecting higher education, forcibly shutting down left-wing academic departments would be nothing more than routine censorship.

Rufo argued that conservatives don't have to sit idly by while "activist academic departments that push left-wing ideology in the guise of dispassionate scholarship" grow at American universities. "The activist disciplines are not inevitable, and decline is always, in part, a choice—one that can be reversed with sufficient courage, insight, and will," he wrote.

"Conservatives have an opportunity to move beyond critique and enact meaningful reforms that will restore the pursuit of truth as the telos of America's public universities," Rufo continued. State legislators, he argued, "should propose the abolition" of activist academic departments.

Rather than being a novel concept, Rufo argued that there is precedent for these kinds of closures. He gave two examples: the closure of the University of California, Berkeley's criminology department in 1974, and the shuttering of the University of Chicago's education department in 1998.

However, neither case involved state legislatures. Regarding Berkeley, Rufo wrote that "Chancellor Albert Bowker shut down the entire School of Criminology, ignoring large-scale student demonstrations, which supporters described as 'militant and spirited.'" According to Rufo, "Bowker justified the closure by citing the need to make budget cuts due to an economic recession, but the political subtext was clear: the radical criminologists had degraded the university's scholarly mission."

The story is similar at the University of Chicago. According to Rufo, "in 1996, after a formal review, the dean of the social science division, Richard Saller, recommended that the university close down the department, citing 'uneven' research and 'low expectations.' It was officially shuttered soon afterward."

In both instances, an academic department was shut down by university leaders themselves, who decided that a particular department was no longer serving the university's mission. Rather than government mandates, these instances—while perhaps colored by the political valence of the departments' scholarship—seem more like routine university self-governance than the state-led crusade Rufo is calling for.

"Administrators, faculty, and students can advance left-wing ideology in their private capacity," Rufo wrote, "but the First Amendment is not an entitlement to state support and taxpayer subsidies." Rather, "legislators have an opportunity to abolish academic programs, such as critical race theory, ethnic studies, queer theory, gender studies, and intersectionality, that do not contribute to the production of scholarly knowledge but serve as taxpayer-funded sinecures for activists who despise the values of the public whom they are supposed to serve," he claimed.

But Rufo is plain wrong, both in his legal argument and in his appeal that academic censorship can be justified as "part of the normal course of business."

"The argument is incorrect. Professors are not mouthpieces for the government. For decades, the Supreme Court of the United States has defended professors' academic freedom from governmental intrusion," Joe Cohn, legislative and policy director at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), tells Reason. "As the Supreme Court wrote in Keyishian v. Board of Regents: 'Our Nation is deeply committed to safeguarding academic freedom, which is of transcendent value to all of us and not merely to the teachers concerned. That freedom is therefore a special concern of the First Amendment, which does not tolerate laws that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom.'"

Rufo also fails to consider how easily his ideas could backfire. "Political winds can change and the targets of censorship predictably change with them," says Cohn. "As FIRE has long warned, do not fall in love with the club that will be used to beat you over the head."

Unfortunately, Rufo's ideas aren't hypothetical. In recent months, several legislative efforts—most notably in Florida—have attempted to quash professors' academic freedom. "Legislative initiatives like the STOP Woke Act and HB 999 seek to use the power of the state to shut down speech and scholarship on politically disfavored views," adds Cohn. "These efforts cannot be squared with our longstanding national commitment to academic freedom."

An argument supporting censorship in the name of "the pursuit of truth as the telos of America's public universities," as Rufo claimed, is ultimately shortsighted. Not only does Rufo fail to see how the powers he would give the government could be wielded against his ideological allies, but he also fails to see how censorship ultimately runs counter to the same American values he claims to support.

"Professors must be able to teach, conduct research, and publish scholarship without fear of viewpoint-based retribution from the government," says Cohn. "And students must be able to learn from faculty who are not muzzled by the state."