He Spent an Extra Two Years in Prison Because He Could Not Find a Place Where He Was Legally Allowed To Live

New York's residence restrictions for sex offenders raise the question of how irrational a policy must be to fail "rational basis" review.

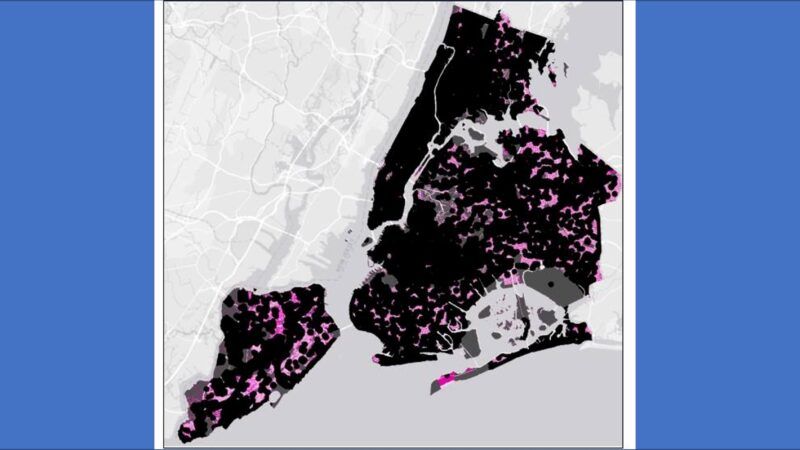

Since 2005, New York has prohibited people on "level three" of the state's sex offender registry from living within 1,000 feet of a school. In New York City, as the above map shows, those "buffer zones" cover nearly all residential areas. Because the state requires registrants to find legally compliant housing before they leave prison, these restrictions mean they may remain behind bars long after they are eligible for conditional release and even after they have completed their original sentences.

That is what happened to Angel Ortiz, who in 2008 was accused of "sexually

threatening a pizza delivery man during the course of a robbery designed to

secure money in order to obtain drugs." After Ortiz pleaded guilty to robbery and attempted sexual abuse, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison plus five years of parole. He became eligible for supervised release after serving about eight and half years. But as New York Times reporter Adam Liptak notes, Ortiz remained in prison because all of the housing options he suggested—his mother's apartment in New York City, along with "dozens of alternatives, including some in upstate New York"—ran afoul of the 1,000-foot rule.

Even after Ortiz had served the full 10 years of his original sentence, he remained in prison. All told, he served an additional 25 months because of New York's residence restrictions.

Last month, the Supreme Court declined to review a New York Court of Appeals decision that upheld Ortiz's continued incarceration. While agreeing that the case "does not satisfy this Court's criteria for granting certiorari," Justice Sonia Sotomayor outlined the "serious constitutional concerns" raised by New York's residence restrictions, which she suggested "may not withstand even rational-basis review."

Since that standard of review is highly deferential, requiring only a "rational connection" between a restriction on liberty and a "legitimate state interest," Sotomayor's assessment is a strong statement about the weak justification for residence restrictions like New York's. But it is consistent with the conclusions of criminologists, who have found scant evidence that the policy actually protects public safety. Several courts and government agencies have concurred that residence restrictions do not work as advertised and may even be counterproductive, undermining rehabilitation and making recidivism more likely.

In a 2017 report that Sotomayor cited, the Justice Department noted that there is "no empirical support for the effectiveness of residence restrictions." It added that the policy may cause "a number of negative unintended consequences" that "aggravate rather than mitigate offender risk."

A study of 3,166 sex offenders who were released from Minnesota prisons between 1990 and 2002 is consistent with that assessment. As of 2006, criminologist Grant Duwe reported in Geography & Public Safety, 224 of those offenders had been "reincarcerated for a new sex offense." Duwe and his colleagues looked at the circumstances of those new offenses to determine whether they "might have been affected by residency restrictions." They asked whether the crimes involved direct contact with a victim younger than 18 within a mile of the offender's residence and whether the first contact occurred "near a school, park, day care center, or other restricted area."

Duwe, who is the research director at the Minnesota Department of Corrections, found that "none of the 224 sex offenses would likely had been deterred by a residency restriction law." While residence restrictions focus on locations where children congregate, "the 79 offenders who made direct contact with victims tended to victimize adults more frequently than juveniles." Duwe also noted that "sexual recidivism was affected by social or relationship proximity, not residential proximity," and that "sex offenders rarely established direct contact with victims near their own homes."

These results and other research, Duwe concluded, "suggest that residency restrictions would have, at best, only a marginal effect on sexual recidivism." He also warned that such policies may be worse than useless. "Recent research has found that a lack of stable, permanent housing increases the likelihood that sex offenders will reoffend and abscond from correctional supervision," Duwe wrote. "By making it more difficult for sex offenders to find suitable housing and successfully reintegrate into the community, residency restrictions may actually compromise public safety by fostering conditions that increase offenders' risk of reoffending."

Based on data from two states, University of Missouri criminologist Beth Huebner and her colleagues likewise found "little evidence that residence restrictions changed the prevalence of recidivism substantially for sex offenders in the postrelease period." In Missouri, the implementation of residence restrictions was associated with a "slight decrease in recidivism," while Michigan saw a "slight increase in recidivism." Huebner et al., who reported their findings in Criminology & Public Policy, said "the results caution against the widespread, homogenous implementation of residence restrictions."

A Florida study reported in Criminal Justice and Behavior compared recidivists to nonrecidivists and found "no significant relationship between reoffending and proximity to schools or daycares." The authors concluded that "proximity to schools and daycares, with other risk factors being comparable, does not appear to contribute to sexual recidivism."

In a 2019 Yale Law Journal article, Allison Frankel, a fellow at Human Rights Watch, looked specifically at the situation in New York. For registrants like Ortiz, she noted, "finding housing means navigating a web of restrictions that are levied exclusively on people convicted of sex crimes and that dramatically constrain housing options, particularly in densely populated New York City." The state's detention policy "continues unabated, despite studies showing that sex-offender recidivism rates are actually relatively low and that residency restrictions do not demonstrably prevent sex offenses," she observed. "Rather, such laws consign registrants to homelessness, joblessness, and social isolation."

Does the irrationality of residence restrictions mean they fail the rational basis test? A federal appeals court thought so. In 2016, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 6th Circuit ruled that retroactive application of Michigan's registration requirements for sex offenders, including residence restrictions, violated the constitutional ban on ex post facto laws. The three-judge panel concluded that there was no "rational connection" between Michigan's policy and a "nonpunitive purpose."

The 6th Circuit noted that research does not support Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy's highly influential claim that recidivism rates for sex offenders are "frightening and high." The court cited "evidence in the record supporting a finding that offense-based public registration has, at best, no impact on recidivism." It added that "nothing the parties have pointed to in the record suggests that the residential restrictions have any beneficial effect on recidivism rates."

In 2015, the California Supreme Court was similarly unimpressed by the justification for a 2,000-foot rule that applied to everyone on the state's sex offender registry. It said that policy bore "no rational relationship to advancing the state's legitimate goal of protecting children from sexual predators."

In his dissent from the New York Court of Appeals decision against Ortiz, Judge Rowan Wilson argued that the prisoner's claims merited heightened scrutiny. But assuming that the majority was right to apply the rational basis test, he said, it is not clear that New York's detention policy can satisfy even that minimal standard.

"The rational basis test is a lenient one," Wilson conceded. But "while rational basis review is indulgent and respectful, it is not meant to be 'toothless.'" The standard "requires that the State action be logical, reasonable, and sensible, even if only minimally so," Wilson said. "Put another way, the State cannot take action that is groundless, counterfactual, or unjust."

While "the asserted government interest in preventing the sexual victimization of

children is plainly legitimate," Wilson wrote, the "chosen means of effectuating the State's legitimate interest in protecting children beggars all rationality." He noted that "courts and scholars alike have recognized that residency restrictions do next to nothing to prevent children from being victims of sex crimes." Continued imprisonment based on that policy, he added, "irrationally thwarts the New York State and City legislatures' goals of fostering the successful reintegration of formerly incarcerated individuals into the community."

The supreme courts of several states, including Alaska, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania, have reached conclusions regarding sex offender registries similar to the 6th Circuit's, deeming these schemes punitive rather than regulatory. When registration requirements prolong imprisonment, as they did in Ortiz's case, it is especially clear that they impose punishment by another name.